- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Ways of seeing

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Gillian Dooley reviews 'The Beloved' by Annah Faulkner

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘God gave me polio?’ Taken aback by her grandmother’s bland insistence on unquestioning submission to divine will, the six-year-old child in Annah Faulkner’s novel The Beloved has already started questioning the articles of faith and the assumptions of the adults in her world, in that penetrating way some children have. Clearly she is not going to take to religion. Other early certitudes fall away as she gets older: Father Christmas; her parents’ love for each other; her mother’s understanding of her deepest nature.

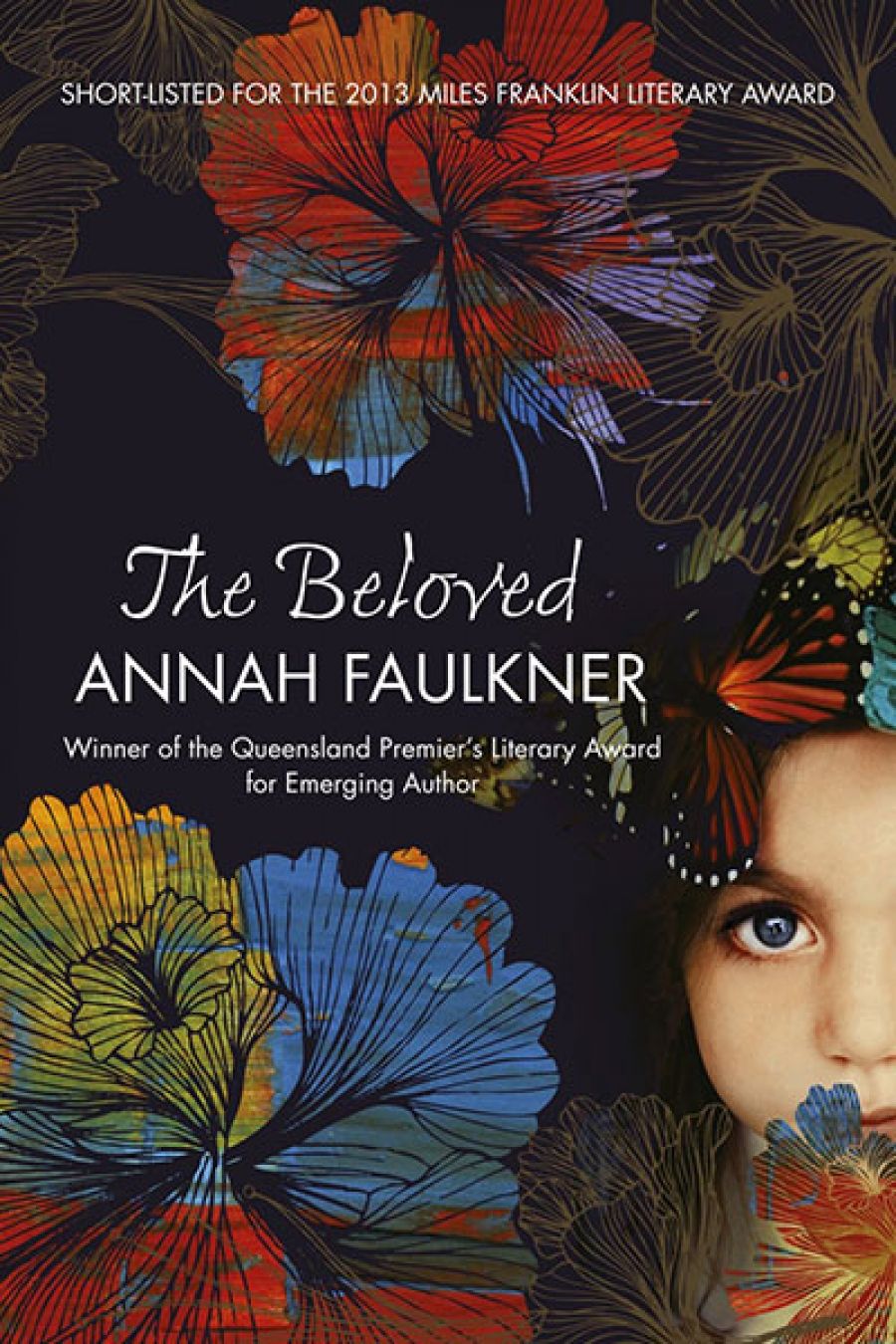

- Book 1 Title: The Beloved

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $27.99 pb, 313 pp, 9781742611556

Roberta (Bertie) Lightfoot is afflicted with polio soon after her sixth birthday. Her stubborn mother, Lily May, refuses to accept the doctor’s prognosis that she will be unable to walk, and forces her to exercise and gradually overcome the worst effects of the disease. Bertie is left with a withered foot and built-up boot, and the self-consciousness they often bring her.

As the urgency of that problem recedes, Bertie becomes aware of something more toxic. Her mother’s stubbornness, having saved her from life in a wheelchair, starts turning against her. Lily May wants a ‘normal’, conventionally high-achieving daughter. She sees Bertie’s synaesthesia, which gives her uncanny insights into people’s thoughts and emotions through the colours she sees in their auras, as a symptom of wilful fantasising. Intent on turning Bertie into the doctor she had failed to become herself, she tries to suppress and then to forbid her passion for art. This all becomes very complicated when Bertie’s father falls in love with an artist, who then becomes a teacher and mentor of Bertie in secret.

It would be difficult, with this highly charged and gripping novel, not to regard Lily May as anything but an appalling mother. How can she not see the agonising choice she is forcing on her child – her beloved child?

Mama had emptied me out, top to toe. For all the pain she’d caused me I almost wanted her gone, but the thought of her leaving us … was unbearable … I had to choose between Mama and art, both of which meant more to me than anything else in the world. How could I? How could I not choose my mother? How could I not choose to paint?

When the inevitable crisis comes, the unfairness of Bertie’s self-accusation is stinging: ‘This woman, my mother, had loved, nurtured and fought for me all my life, asking for nothing in return except that I make the most of what I had.’ No. What she has asked in return is that Bertie change her fundamental nature and become a different person.

The Beloved is set mainly in Port Moresby. This is an interesting aspect of the book. There is no reason why Australian novels shouldn’t be set there, where so many Australians have lived, Annah Faulkner included. There is a small amount of incidental detail attached to this setting: some pidgin dialogue; an appalling incident concerning the family’s pet dog; a maid who, though a wise and sympathetic presence in Bertie’s life, is unfortunate in her choice of male companions; the occasional trip to the interior bringing with it bracing and formative experiences. But the novel could be set anywhere. There is little engagement with PNG culture, and although most of the major characters are expats in the Port Moresby of the 1960s, this is not particularly salient. The setting pales against the vivid central drama of the novel – Lily May’s battle with Bertie for her heart, mind, and soul.

At first this novel feels like undigested childhood memoir, while towards the end it tips towards literary over-determination. Bertie’s friendship with Stefi Breuer, child of Hungarian immigrants, provides a foil for the bitter inter-generational conflict: when Stefi wants to learn ballet, her mother shrugs and says ‘fine’, while Lily May destroys Bertie’s paintings and sketchbooks whenever she finds them. There is a little scene where Bertie encounters the boy on whom she has a pre-pubescent crush. While Chris tries on sneakers, Bertie questions him about his feelings for her, while he prevaricates politely. ‘I don’t think this fits me after all,’ he declares, pulling off a shoe, before bidding her a friendly but final farewell. A late chapter begins, ‘The tide was turning.’ It is literally true – there is a nice description of Bertie observing the action of the waves on the sand – but it is also clearly true of her life.

Faulkner has created a wonderful character with Bertie – a passionate individual, drawn to the unconventional, with a unique way of seeing, depicting, and describing the world. Stefi, according to Bertie, is alternately restless and chattering and ‘as silent as a pillow’. Bertie’s parents take her to a wedding, where ‘a priest in a ruffled white collar sandwiched the hands’ of the happy couple ‘in holy matrimony’. When she first meets Chris, who has ‘golden hair and eyes like the sea’, she feels ‘horribly and brilliantly visible’. Bertie’s development as an artist has intrinsic interest, intensified by the context: she is gaining this knowledge in secret from the woman who loves her father, risking disastrous consequences if her mother finds out. But the greatest triumph of this novel is the voice of a sceptical, passionate, bright, rebellious child who has an understanding beyond her years, and the bravery and intensity of her struggle to be herself.

Comments powered by CComment