- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

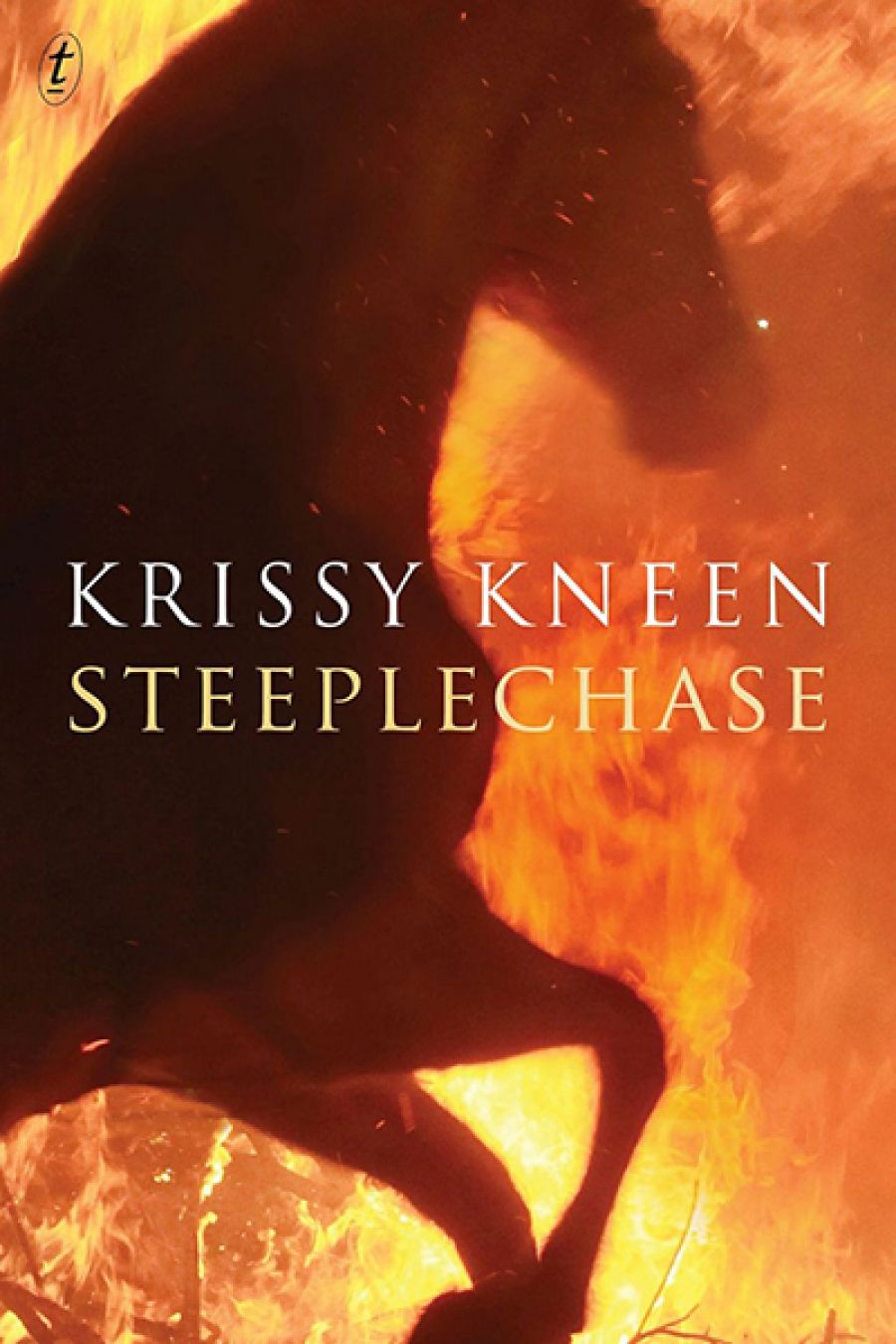

- Custom Article Title: Wendy Were reviews 'Steeplechase' by Krissy Kneen

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Hall of mirrors

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘My sister Emily likes ponies and show jumping and arenas.’ Steeplechase, Krissy Kneen’s fourth book, opens innocently enough with this unremarkable announcement of a common girlhood infatuation. Before the first paragraph ends, this innocent observation is tempered by the obviously unwholesome quality that underpins the imaginative equine play of two young sisters. Foreshadowing the intricacies of this sibling relationship, the steeplechase game highlights Emily’s dominance and the narrator’s incompetence. It is also laced with psychic and physical cruelty: ‘She tells me that I am a bad horse, a lazy horse, a slow horse, and I take the whipping silently because it is true. I am a bad horse. I am not any kind of horse at all.’

- Book 1 Title: Steeplechase

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 pb, 224 pp

Fast-forward: the protagonist Bec Reich, now in her late thirties and an art teacher in Brisbane, is still living in the shadow of her sister Emily, an internationally renowned artist living in Beijing. Emily is also famously schizophrenic. Reluctantly involved in an affair with a younger student, Bec is mired in a ‘foetid pit’ of insecurities stemming from her childhood experience; she is also recovering from surgery. It is in this wounded, vulnerable state, her mind addled by morphine, that Bec receives a bewildering phone call after a twenty-three-year silence:

I force myself to take the phone away from my ear and search for the last incoming call. I store the number under one word, ‘sister’. I know I should have used her name but it is all I can think of in this moment. Sister. My sister just called me and I spoke to her. I imagine the words as if they were written in a book: Twenty-three years later my sister called.

The purpose of Emily’s call is to invite Bec to China for the opening of her new exhibition, an invitation that Bec initially tries to resist. The epigraph from Nabokov’s Lolita presages a cataclysmic event that drives the narrative: ‘I leaf again and again through these miserable memories and keep asking myself, was it then, in the glitter of that remote summer, that the rift in my life began?’ It is evident from the outset that Bec’s past holds some significant childhood trauma, an unspeakable ‘terrible thing’ from which Bec has recovered, or been ‘cured’, with the help of psychiatry. The unexpected reconnection with Emily instantly propels Bec back to her teenage past, to the site of an episode from which she quickly flees, seeking solace of memories of a time ‘when I felt safe and secure and locked up tight’.

Trauma is often characterised by the failure of narrative. Stylistically, the text of Steeplechase is characteristic of trauma narratives where memories of past wounding cannot be assimilated into the story of self but instead exist as disembodied images and flashbacks that return unbidden and with some of the impact of the original experience. Steeplechase, fractured and fragmented, skips between memories of childhood and the present day. This episodic format cuts the text, favouring gaps and interruption over continuity.

Steeplechase will be seen as a departure for Kneen, who is best known for her erotic writing. The Lolita epigraph foreshadows the human sexuality at the heart of the story, but also the uneven power relationship that often characterises sexual roles. Bec’s memories of teenage sexual awakening sit alongside one of the text’s most intensely disturbing scenes: during a psychotic break, Emily brutally rides her sister like a horse, forcing a makeshift cloth bit into her mouth.

Bec is no stranger to living with madness. The girls are raised by their grandmother, for their mother, who lives with them, has also ‘snapped’. The fragments of Bec’s memories reveal Emily’s increasing deterioration in the summer of her fifteenth year when Bec was forced to ‘stand by uselessly as the madness takes her’. Figuring Emily’s departure as abandonment, Bec willingly follows her sister into a shared psychosis. It is from this that she has subsequently recovered, albeit tenuously:

Shared Delusional Syndrome. Folie à deux. I know what was wrong with me. I have been diagnosed and there is a certain relief in having a name for your troubles. I am cured now. The madness belonged to Emily, and I borrowed from her for a while but now I am sane.

Where trauma disrupts and defies conventional modes of representation, art can be an enabling medium. The narrative framework is carefully crafted; this is a text with an architectural sensibility of a hall of mirrors. The principal themes of artistic genius, madness, and self-realisation are beautifully conveyed through metaphors of restoration and forgery. Kneen introduces the dénouement with subtlety, so that one is almost oblivious to the shards of memory assembling into a coherent narrative. Slowly, a portrait of the past is reconstructed, a story exists where there was none, catharsis is achieved and wounding rendered intelligible by art.

Steeplechase is understated and potent. Kneen’s restrained prose is elegant in its simplicity. Despite the highly emotive subject matter, it never becomes overblown or hysterical. The premise behind steeplechasing is that the obstacles make the horse demonstrate agility, power, intelligence, and bravery. Kneen achieves all of these qualities in her first novel.

Comments powered by CComment