- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Subheading: Dancing through a maze of possible mimesis

- Custom Article Title: Chris Wallace-Crabbe reviews 'Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures' by Leonard Barkan

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The eye's trade

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Simonides of Ceos is said to have declared that ‘Painting is mute poetry, poetry a speaking picture.’ All of us know something of what he means, about our thirst for information from the arts: and, if you like, our scrabbling for the visible within a text. One half of his mirrored pronouncement is verified by those people who, in an art museum, hurry to the curatorial information alongside a picture. They want to discover what the painting is about. But the sought-after ‘aboutness’ keeps slipping away from the viewer, much as the point – but is it a point? – of a poem does.

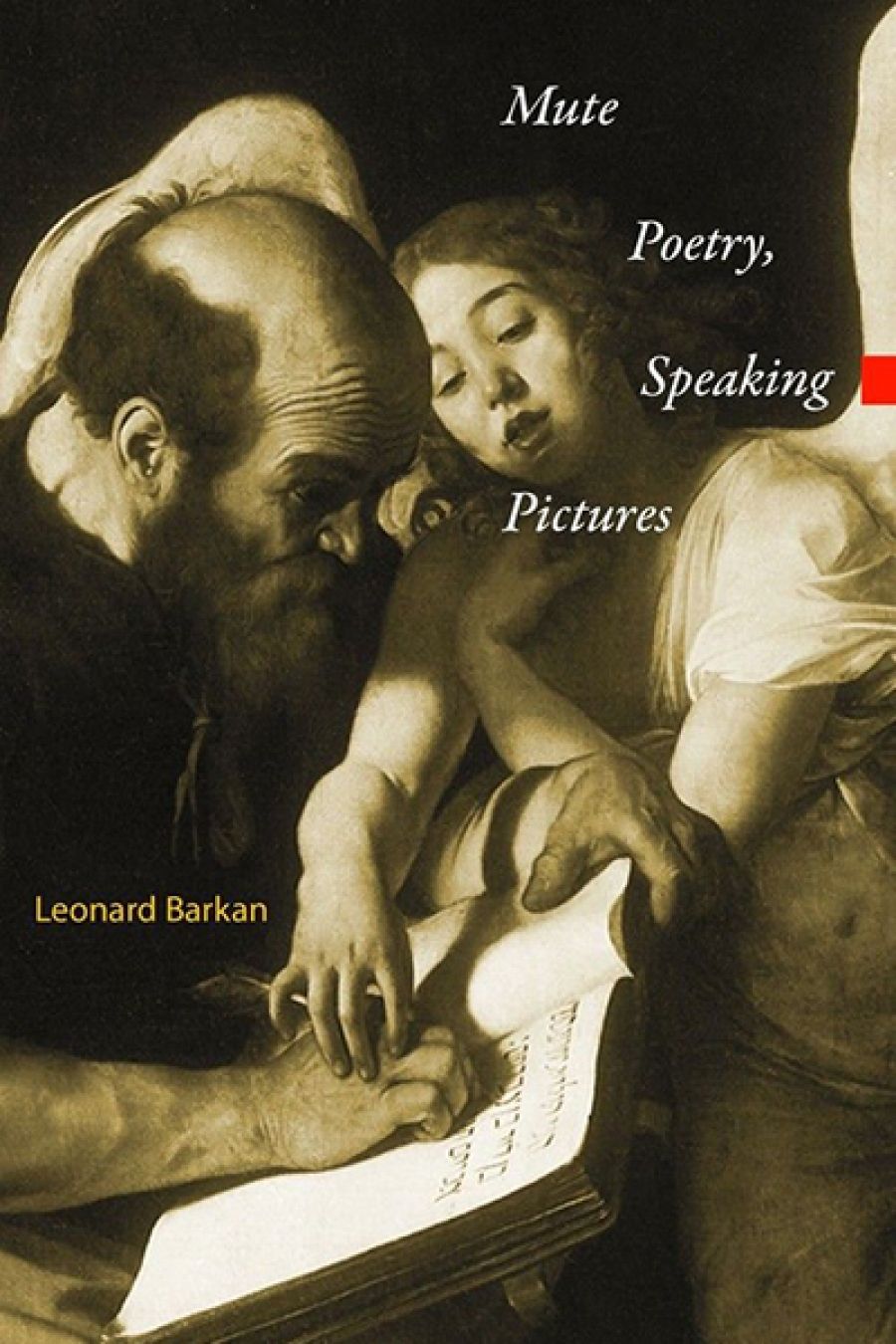

- Book 1 Title: Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures

- Book 1 Biblio: Princeton University Press (Footprint Books), $31.95 hb, 207 pp

Ah yes, poems: sometimes I think with pleasure of A.E. Housman’s coy response that he ‘could no more define poetry than a terrier can define a rat’. But there are carnivorous problems with his simile; besides, it is an easy way out of our serious questioning.

This porous frontier of art is the territory of Leonard Barkan’s Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures. His invitingly learned and fairly short book ranges from classical Greek thinkers to the Renaissance theatre of Shakespeare and of the solidly illusionist Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza. Of course, solid illusions are an oxymoron, but a most honourable one. Perhaps the Teatro could serve as a symbol for all the concerns that are so richly explored in this book.

Barkan manages to be alert to those ancient philosophical speculations and witty about them. Thus, when taking up Socrates’ comparison of the practising painter to somebody who wanders around capturing images in a portable mirror, he writes that ‘the derivation via the mirror turns the painter into a kind of reality-Xeroxing idiot savant’. Dealing with metaphor and simile, he tells us that Romanians have been warned against comparing grandmothers with machine guns. Moreover, he retails Pliny’s fable about a horse-painting competition, which was finally judged by the horses themselves. One is suddenly tempted to think of Swift’s Houyhnhms as our ultimate moralists.

Late in the book, we are reminded that ‘the terms counterfeit for the visual arts and fiction for the literary arts are not very different from each other’. Barkan is such a strenuous thinker that he keeps thrusting the arts and their ostensible claims back into the trembling acres of ambiguity. He leads us, for instance, to one of the most visually compelling passages from Shakespeare, the Dover Cliff prospect in King Lear: how vividly present to us is that rich, detailed downward view. But Edgar is making it all up for the blind Gloucester; the cliff and its diminished denizens just aren’t there at all. Shakespeare has played with us, brilliantly. This book enjoys pressing into these aesthetic paradoxes. Mimesis (or imitation) has traps for us everywhere we look. Streeton’s actual landscapes didn’t have gilded frames, nor Aphrodite a plinth. The arts we love keep dancing us through a maze of possible mimesis.

Barkan also takes on board the poetic art of ekphrasis – a word unloved by students of poetry, but a common enough practice. It denotes the ‘verbal presentation of a visual object inside a literary work’. Yet such a presentation can scarcely be mimetic, given the visual limitations of lettering, of typographic or handwitten signs. The poet (it is usually a poet) has to seduce a reader into acquiescing in reception of an ‘image’, some transaction as vivid as a red wheelbarrow.

What a pity it is that Barkan makes no mention of the late Peter Steele, Australia’s finest ekphrastic poet. Not only did Steele write a great many such poems, based on work in various museums, especially in the National Gallery of Victoria, but he has offered reflections on how ‘the eye’s trade is different from the mouth’s’, not least when he writes that

From time to time a good deal of huffing and puffing goes on about this matter, but … there is still a great deal of genuine complexity in the whole affair. Just what counts as a satisfactory interplay between a painting and ‘its’ poem is something which the poet will be addressing all the time of writing: and, in turn, the reader who is also a gazer will, ideally, be a participant of sorts in that interplay.

Barkan’s book is precisely addressed to the participating reader who is also a gazer; or even a literate taster of bitter herbs, surprisingly foregrounded here in a quotation from Vasari, who once evoked the way ‘bitter things sometimes give marvellous delight to the human palate’, allowing chicory to ally itself with Piero di Cosimo’s ‘ horrible Masque of Death’.

Johannes Vermeer, The Milkmaid (c.1658)Further, was our diurnal world ever so trustworthy as in Edward Thomas’s lyric ‘Adlestrop’, for all that it evokes a train’s random stop? Does anything else matter when we stop in front of Vermeer’s Milkmaid (c.1658) and stare at the substantial liquid pouring from her jug, while perfectly still? Successful works of art can still our desires for a while, at least.

Johannes Vermeer, The Milkmaid (c.1658)Further, was our diurnal world ever so trustworthy as in Edward Thomas’s lyric ‘Adlestrop’, for all that it evokes a train’s random stop? Does anything else matter when we stop in front of Vermeer’s Milkmaid (c.1658) and stare at the substantial liquid pouring from her jug, while perfectly still? Successful works of art can still our desires for a while, at least.

One chapter is entitled ‘Desire and Loss’. We need not be surprised that Petrarch looms large here; but the account has zigzagged from nude classical statues which add implicit narrative by having clothing close by them, through a claim that mimesis is innate, pleasurable, and even somehow autonomous, to the famous creation of Petrarch’s Laura. This young woman of Avignon was the founding muse of his poetry: as evoked in complex ways, she enabled him to ‘script a lifelong romance ... around episodes of discovering material remains that blurred the distinctions between book and picture’. In doing so, he wrestled with a chain of precedents. However, this chapter calls for close rereading, so subtle is its cross-cultural argument. It is the book’s historical core

Mute Poetry is densely packed, but clear. Barkan is drawn to paradox, to the wet watermelon seeds that slip away between our fingers. Often he lingers over self-questioning works. Indeed, had he come down beyond what has now become the Early Modern period, he would surely have found delight in Camus’s self-diminishing story ‘The Artist at Work’, which ends up close to a Beckettian zero.

Comments powered by CComment