- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

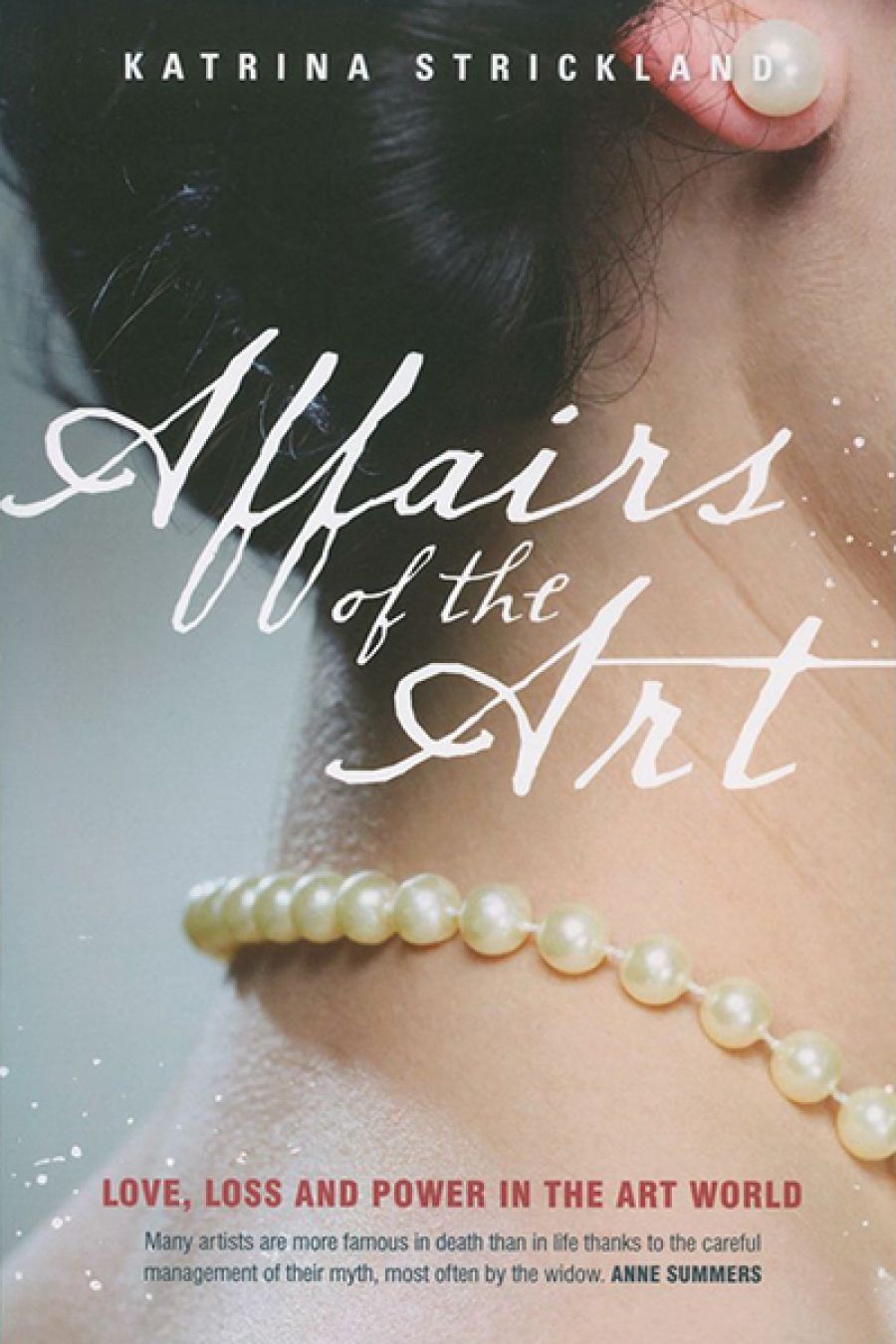

- Custom Article Title: Mary Eagle reviews 'Affairs of the Art' by Katrina Strickland

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Keepers of the artistic flame

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What happens when a famous artist dies, leaving a wife, husband, or children to tend the flame? The question recurs in Ian Hamilton’s spellbinding Keepers of the Flame (1992), an account of a dozen literary estates over a period of three hundred years, and remains suspended in this journalistic assessment by Katrina Strickland of the management of Australian art estates in our own time.

I felt the strength of a widow’s commitment in 1992 when Maisie Drysdale gave me Hamilton’s book. At the time, I was procrastinating about writing a biography of her first husband, Peter Purves Smith. He had been dead more than forty years; Maisie had remarried in the 1960s and was now an old woman twice bereaved; but she had not forgotten. Through her deliberate gift she intimated that I shared the responsibility of shoring up her dead young husband’s reputation, warned me that she had a widow’s passion, and reassured me that she had taken Hamilton’s point (up to a point).

- Book 1 Title: Affairs of the Art

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $34.99 pb, 261 pp

‘It seems to me,’ wrote Hamilton, ‘that fifty years is not too long for us to wait for the “whole truth” about a private life. In the meantime, no one should burn anything, however certain he or she might feel about what the lost loved one “really would have wished”.’

Keepers of the Flame ended with a Gothic warning from Philip Larkin that an objective assessment is not possible in the lifetime of the keepers of the flame:

That is not to say that we have no picture in the meantime: nearly always we have, but it is put out by precisely the people (widow, family, etc) who are standing in the way of complete documentation. There may be good human reasons for this, and in any case the interim picture will be far from false, but it will almost certainly require ultimate modification, which (again almost certainly) will come as something of a shock.

Widows of art can’t help being aware of their unsavoury reputation as keepers of secrets. To guard a reputation is one thing; their heavier responsibility is to keep works of art alive. Art historians, who focus on an artist’s career in relation to every influence they can think of in his or her lifetime, rarely direct anything like the same attention to the leading actors in the postlude, yet how an estate is managed can have a big influence on an artist’s reputation. One of Strickland’s stories is of George Baldessin’s widow, Tess, who within five years of her husband’s premature death in a car accident suffered the unexpected deaths in a house fire of her new partner’s children. Reeling, she gathered her remaining family around her and left Australia, locking the studio behind her. Twenty years later she returned, to find that Baldessin the artist had been sequestered from public notice along with his neglected works of art.

Howard Arkley in his studio, 1991 with some of his source material (photograph from Carnival in Suburbia, The Art of Howard Arkley by John Gregory, Cambridge University Press, 2006)One virtue of Strickland’s book is the information scattered throughout about the effect on widows or children of major artists, who are converted overnight into public figures. Needing a quiet space to cope with death, they are instead torn from privacy, embroiled in decision-making, and subjected to the scrutiny of the media. The result can be, as Howard Arkley’s widow, Alison Burton, found, that she ‘[d]idn’t get to grieve … In the early part it was always contaminated by the things that were going on outside of my relationship with him. I found that really, really distressing, that I couldn’t grieve properly.’

Howard Arkley in his studio, 1991 with some of his source material (photograph from Carnival in Suburbia, The Art of Howard Arkley by John Gregory, Cambridge University Press, 2006)One virtue of Strickland’s book is the information scattered throughout about the effect on widows or children of major artists, who are converted overnight into public figures. Needing a quiet space to cope with death, they are instead torn from privacy, embroiled in decision-making, and subjected to the scrutiny of the media. The result can be, as Howard Arkley’s widow, Alison Burton, found, that she ‘[d]idn’t get to grieve … In the early part it was always contaminated by the things that were going on outside of my relationship with him. I found that really, really distressing, that I couldn’t grieve properly.’

For Lyn Williams there were times, early on, when the burden of representation seemed too much: ‘it was just too hard; it’s like living your life in the past altogether’. She notes: ‘It’s different now, and I realise I probably know a lot about the work. It’s not an emotional thing like it used to be.’

Things to be decided by the executor, in lieu of the artist, include such tests of judgement as authenticating works, making appropriate sales, donating and lending works, giving or withholding copyright, providing, hiding, or destroying specific information, opening every aspect of the artist’s life to examination, or, conversely, defending privacy and opposing the publication of some matters. Few of those left holding the reins are artists themselves: their election rests on the fact that they have known the artist intimately. Hamilton and Strickland agree that as a rule the managers of estates have steered by what they think the artist would prefer. Ironically, past wisdom would suggest that keepers of the flame are hampered when they filter every decision through an internalised image of the artist. Unlike the swift intuitive creators they act for, the stand-ins are necessarily behind the game: second-guessing makes them look backward; looking over the shoulder renders them clumsy; responsibility inhibits them; in turn, they can be inhibiting. The more successful keepers of the flame are experts in their own right. ‘Fred told me what he thought I should do, but he left it to me to organise, to have the freedom to do as I saw fit,’ said Lyn Williams. She gave herself the time and space to study the issues, and over thirty years has become the most knowledgeable of the experts on the art of Fred Williams – no mean feat, since the other experts include two giants in the Australian art community, James Mollison and Patrick McCaughey.

It is clear from the stories told by Hamilton and from the conversations and marketing ploys reported by Strickland that an artist’s reputation is tied to social values. The actors’ cultural moorings are very apparent in Hamilton’s potted histories, where Augustan dignity wars with tittle-tattle, Romantics strive mightily in sturm and in drang, Victorians suffer the toxic effects of morality, and twentieth-century estate managers travail in psychology. Hamilton did not need to subject his keepers of the flame to heavy-handed historical analysis: they did this work themselves. The question is, does Strickland’s ‘picture of a particular moment in time’ likewise mirror the wider Australian culture?

Affairs of the Art is the truth portrayal we are accustomed to from the media. Juicy stories abound, yet, in marked contrast to past secrecy, today’s celebrities seem transparent under the stringent gaze of the media. With no secrets to winkle out, Strickland has seen her work as assembling information. She covers a wide selection of estates and explores the newsworthy angles of the subject. Her affection for her living subjects shines through what ‘is as much a book about love, grief and survival as it is about power, duty and the machinations of the Australian art world’.

My difficulty is with her emphases. I would have thought the core of the subject to be the reputation of works of art during the initial fifty-year period after the artist’s death. I hoped for more about the art, expected a focused analysis of the concepts the managers of estates bring to their task, looked for a sustained appraisal of the enrichment or thinning of artistic reputations during the initial several decades after death, and fancied Strickland would get down to the status of individual works of art during the same period. I should have realised that her expertise with the art market and modest disclaimer of other art-historical expertise would be determinative. To answer the question I raised above: if the core values of our society are newsworthiness, the market, and the short term without regard for the long, then the picture drawn so skilfully by Strickland is representative of Australian culture. In such a culture, fluctuations in the economy add up to posterity. Conversely, if the core values of our society extend beyond those things, there is a richer story to tell.

Comments powered by CComment