- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

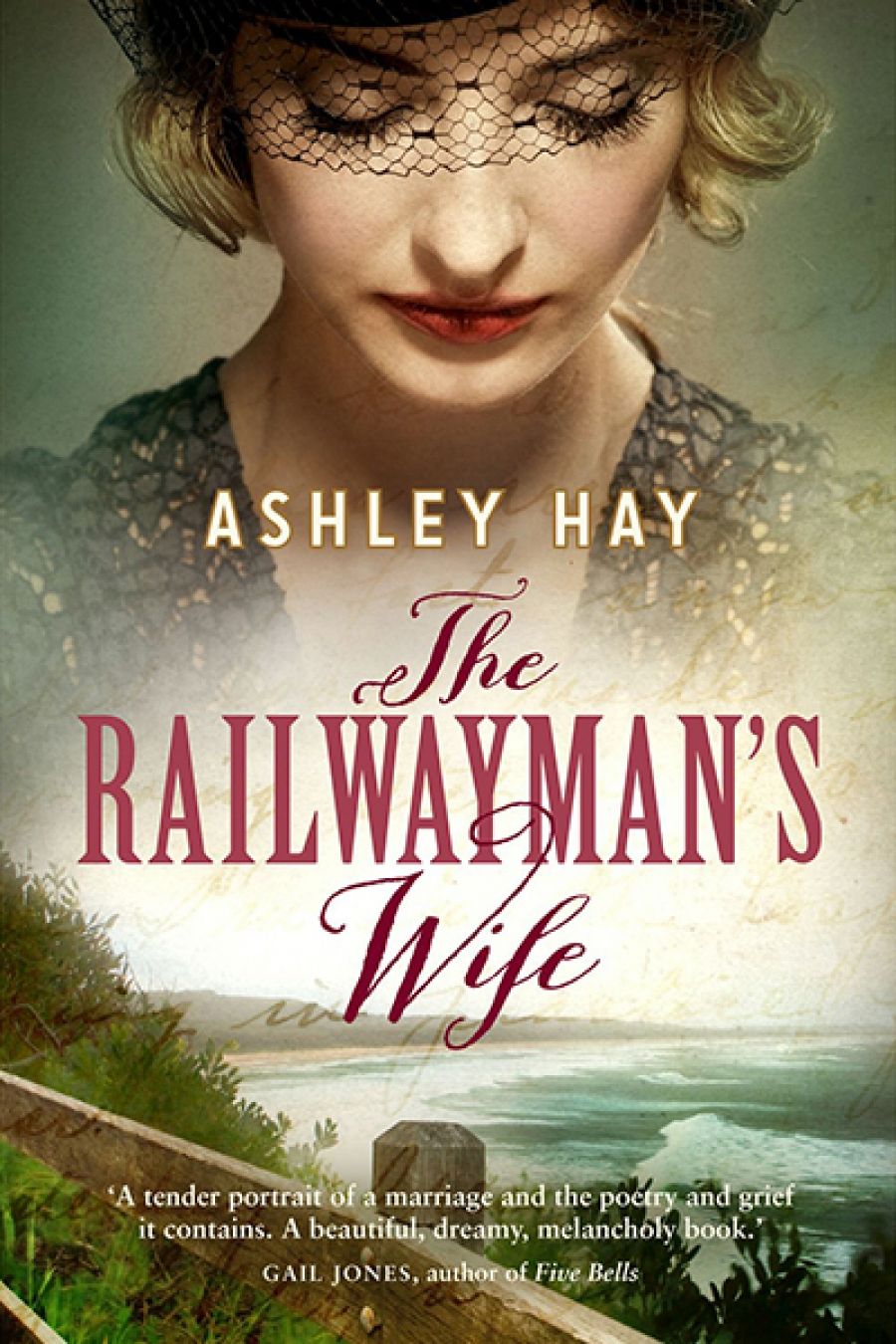

- Custom Article Title: Patrick Allington reviews 'The Railwayman’s Wife' by Ashley Hay

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Seeing things differently

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As a woman and her daughter prepare to attend a memorial service for their husband and father, a railwayman, the girl offers the woman her kaleidoscope: ‘You could borrow this, Mum [...] You said it was good for seeing things differently.’ It is a resonant moment, the promise of a magical but fleeting distortion of reality both lovely and desperately sad. The scene also encapsulates The Railwayman’s Wife, a novel imbued with death and the hard slog of new beginnings – and with notions of ‘seeing things differently’.

- Book 1 Title: The Railwayman’s Wife

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 256 pp

The Railwayman’s Wife, Ashley Hay’s second novel, follows her highly original début, The Body in the Clouds (2010). Before that, she published four books of non-fiction (two in collaboration with photographer Robyn Stacey) on subjects as diverse as eucalypts and the short, unhappy marriage of Lord Byron and Annabella Milbanke. Whether producing fiction or non-fiction, Hay’s prose possesses a simple grace: stories and ideas matter to her, but so too do style and mood.

The Railwayman’s Wife is set three years after the end of World War II in the seaside town of Thirroul, south of Sydney (where D.H. Lawrence wrote Kangaroo, as Hay weaves deftly into her story). From its opening pages, this pensive novel is studded with telling observations about the claustrophobic nature of small towns and with luminous descriptions of landscape: ‘And there’s the ocean, the sand, the beginnings of this tiny plain that has insinuated itself, tenuous, between the wet and the dry.’

Hay tackles big themes, including grief, the meaning (for those still living) of different types of death, the awful and elongated legacy of going to war, and the perplexing nature of love. She uses three central characters to distil – and diffuse – all this weightiness into something deeply personal, even private. At the story’s centre is Ani, who, in a town full of war widows, is mourning the sudden death of her husband, Mac. Ani is determined to forge a new and independent way for her daughter and herself, but she is equally determined to preserve Mac’s memory. Hay offers a searching portrait of Ani, not least the public version of herself that she presents to the townsfolk while her mind adjusts to her distressing new circumstances: ‘She breathes, feeling her way back towards inconsequential conversations.’

Then there is Roy, a poet who, following the war, has inched his way around Australia before returning to town to live with his sister and take long walks. Overwhelmed by what he has seen and done, by ‘the noise and the waiting’, he cannot sleep, let alone contemplate writing poetry again. Roy’s old friend Frank, a doctor, is also struggling with his war experiences, burdened by his inability to save the lives of some of the shattered people liberated from camps in Europe at the war’s end.

The story builds slowly and only comes fully to life once Ani becomes a librarian at the small Railway Institute library (throughout the story, but without labouring the point, Hay emphasises the importance of books). Both Frank and Roy use the library, allowing Hay to contrast the disparate feelings and experiences of three damaged individuals: a woman mourning her husband, a man who has killed other men, and a man who could not prevent death.

For Frank, borrowing library books seems a secondary pleasure to engaging in rants that he directs at Ani and the world in general; later, he is contrite. Roy unburdens himself on both Ani and Frank in self-excoriating fashion: ‘I need to work out what kind of chump finds poetry in the middle of mud and blood, and can’t string a sentence together about this mountain, this sunshine, this sky and this place.’ Roy glimpses in Ani the possible wellspring of his rebirth, as a poet and as a human being, while Ani resists the temptation fully to contemplate her feelings towards Roy.

Hay’s unhurried approach to storytelling gives the prose a meditative feel, through which, intermittently, sharper-edged observations cut to devastating effect. For example, on one occasion, Roy’s sister, Iris, tells Ani that time cures all ills. In response, Ani casts aside her usual politeness and self-censorship to serve up a vehement rebuttal. Iris, who was once close to Frank and hopes to be again, is unimpressed: ‘Don’t say that they won’t all come back, the ones who lived. Don’t condemn us all to widowhood, now that you have to make sense of it.’

Despite it being the source of the novel’s potency, at times Hay’s unhurried approach leaves the story cast a little adrift. And sometimes – not often – the central characters seem to come together so that they might self-consciously tease out matters of grief and love. On these occasions they seem somewhat distant from the jagged edges of their pain, as if they are performing a part, delivering lines, more so than experiencing their visceral emotions.

A dramatic event punctuates the book’s climax. Initially, this event left me underwhelmed, dissatisfied that a key element of the story remained under-explored. Upon reflection I have changed my mind: Hay has crafted an entirely apt ending to a novel that is about the unpredictability of life and ‘the oddness of history’. In The Railwayman’s Wife, the essence of loss is elusive, and the detritus of grief not easily swept aside.

Comments powered by CComment