- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Sculpting with time

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Mothers of America

let your kids go to the movies!

get them out of the house so they won’t know what you’re up to

it’s true that fresh air is good for the body

but what about the soul

that grows in darkness, embossed by silvery images …These lines from Frank O’Hara’s 1960 poem ‘Ave Maria’ seem wistfully nostalgic now that you can watch Lawrence of Arabia on your iPhone on a tram, an Israeli missile vaporising a Hamas leader, your friend’s Bali holiday on Vimeo, the latest in S&M on an iPad, or a 3D vampire zombie franchise blockbuster in your home theatre, should you be so inclined.

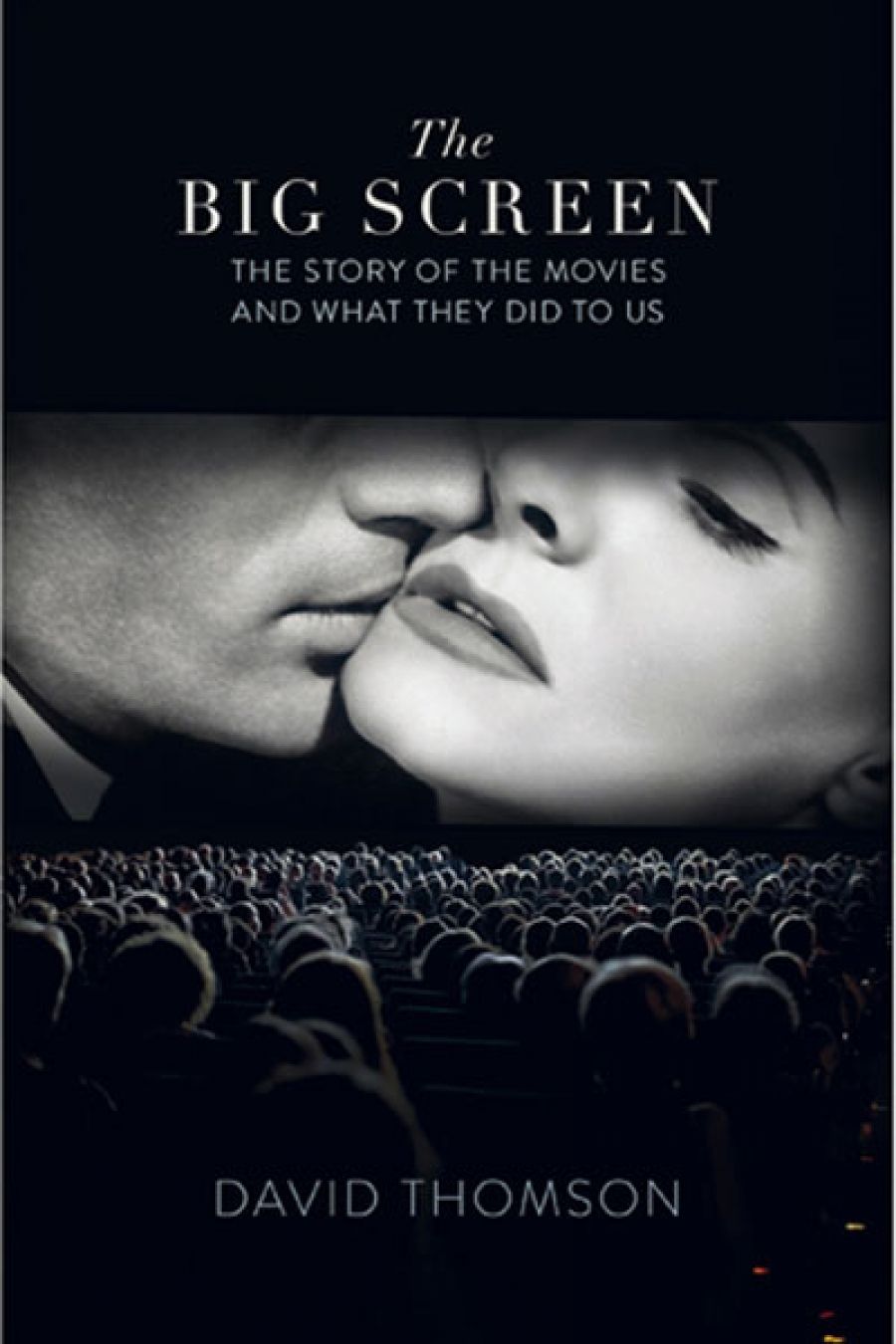

- Book 1 Title: The Big Screen

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Story of the Movies and What They Did to Us

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $49.99 hb, 603 pp, 9781846143144

David Thomson – Englishman, film school graduate, long-time Californian resident, screenwriter, and author of twenty-three books – chronicles our experience with the play of light on screens. If there were an Oscar for film criticism, he would win it. He pines for the golden age of cinema that nurtured him. He yearns for the splendour of Renoir, Kurosawa, Welles, and Antonioni. He sports an elegant turn of phrase.

In a 1997 essay, ‘20 Things People Like to Forget about Hollywood’, Thomson writes:

… lying is the magic in great acting. There are people who won’t hire or even read an actor until he’s a proven, expert, drop-dead, unaging liar … People once loved Hollywood because they hoped that the light on the screen could tell great stories to everyone. We know now that the flicks are only lies told for exploitation. Which is very likely what they always were, only now we are less gullible.

He seeks revelation. On Antonioni’s L’Avventura (1960): ‘La Dolce Vita is like an old shoe, ruined, found on a beach. L’Avventura is a fresh footprint, still warm.’ He retains adolescent wonder. In a 2001 column on David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive: ‘Like a road, with a car, do you just let the vehicle drive over you? Or is it that you are the car, spinning in stasis, as the tarmac unwinds beneath you? I don’t ask, I just go with it.’

He abrades the less than talented. In his New Biographical Dictionary of Film he writes about Keira Knightley: ‘She is astonishingly beautiful. But Keira is about as interesting as a crême brulée where too much refrigeration has killed flavour with ice burn. She is still more credible as a faintly animated photographer’s model than as an actress.’

He relishes female beauty. He has no qualms about the probity of his very male gaze. In his Have You Seen? A Personal Introduction to 1000 Films (2001) on Thelma and Louise (1991), he wrote:‘If it’s a film about sisterhood as a new element in our discourse, then I think the suicide is as regrettable as the discreet absence of sex between the girls.’ He is alert to the way the camera reads faces and allows us to project our fantasies into the wide close-up eyes of a Garbo or Dietrich. This contrasts with our reaction to the magnetic live presence of a Cate Blanchett or an Ian McKellen. Blanchett as Ophelia to Richard Roxburgh’s Hamlet eclipsed the other actors on stage. Yet on screen Blanchett is strangely disengaged and desexed.

Thomson’s concern is how we react to the myriad screens in our lives. He begins by examining the photographic sequences of Muybridge, whose images of a naked man splashing water from a bucket and of a horse caught mid-gallop still intrigue over a century later. Thomson ends fearfully in the age of Facebook, concerned that the proliferation of screens alienates and dehumanises us rather than joins us by new means.

Peter Weir’s The Truman Show (1998)is the only film directed by an Australian that Thomson discusses in The Big Screen (he is more alive to the dearth of women in the pantheon of film directors). For Thomson, Weir catches the duplicity of movies. He describes the Jim Carrey character’s escape by boat, coming hard up against the diorama that is also a screen that both masks and reveals, as one of the most expressive moments in the history of film. Truman’s boat crashes through the wall of Plato’s cave.

On his way to The Truman Show, Thomson spins an entertaining yarn about the evolution of the art form of the twentieth century. Part One deals with the era from the Lumières to post-World War II. He combines gossip about the leading lights with astute observations about influence and social context. He stresses the contribution of Jews from East Europe to the business and art of the movies.

Part Two begins with Sunset Boulevard (1950) and the postwar disillusion that dissolved what he perceives as the unity of the audience. Television becomes the ever-present screen in every living room. He reminds us how we blithely accept advertisements interrupting television programs when a commercial break in the middle of a Beethoven symphony or a U2 concert would appal.

Part Three is headed ‘Film Studies’. It examines the intersection of film and other art forms. Thomson shows how Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (1926)uses film-editing techniques. Of Last Tango in Paris (1972) he writes:

… the more boldly a movie tried to deliver a sexual experience, the more surely it exposed its own artifice or falsehood and the more clearly it told us we were in our ‘there’, in the dark, not on the screen, not having sex. The desire was thwarted. The overwhelming promise of the medium was a fleshless seduction.

In Part Four, ‘Dread and Desire’, he examines how, with the ubiquity of pornography, sex has sunk to a performed process without meaning or desire. He looks at how Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) represents a cinema as gravity-free and entertaining as Tom and Jerry, in which sensation has eclipsed sensibility. He discusses the fearful rhapsodies of violence of the very Catholic Scorsese and the looping spiel of the autodidact Tarantino.

In the epilogue, titled ‘I Wake up Screening’, he writes:

It was John Berger who first noted that while a photograph seemed to summon presence, it also evoked absence. The base function of film and its successors is not just to join reality but to adjust to the screens that keep us from it …When my youngest son saw the second plane enter the World Trade Center tower on live television he asked, ‘What movie is that from, Dad?’

The book ends in something like despair:

Six hours a day of American television, done over two or three decades, can leave you with the numb discovery that all the irony and superiority you were feeling has turned to waterlogged depression … [Our] array of watching devices … might … also be the lineaments of a coming fascism …

Andrei Tarkovsky described film-making as sculpting with time. Thomson finds Tarkovsky humourless, but the Russian director was a poet of the cinema. His successor is out there somewhere, playing with a cheap digital movie camera and editing on a laptop.

Comments powered by CComment