- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

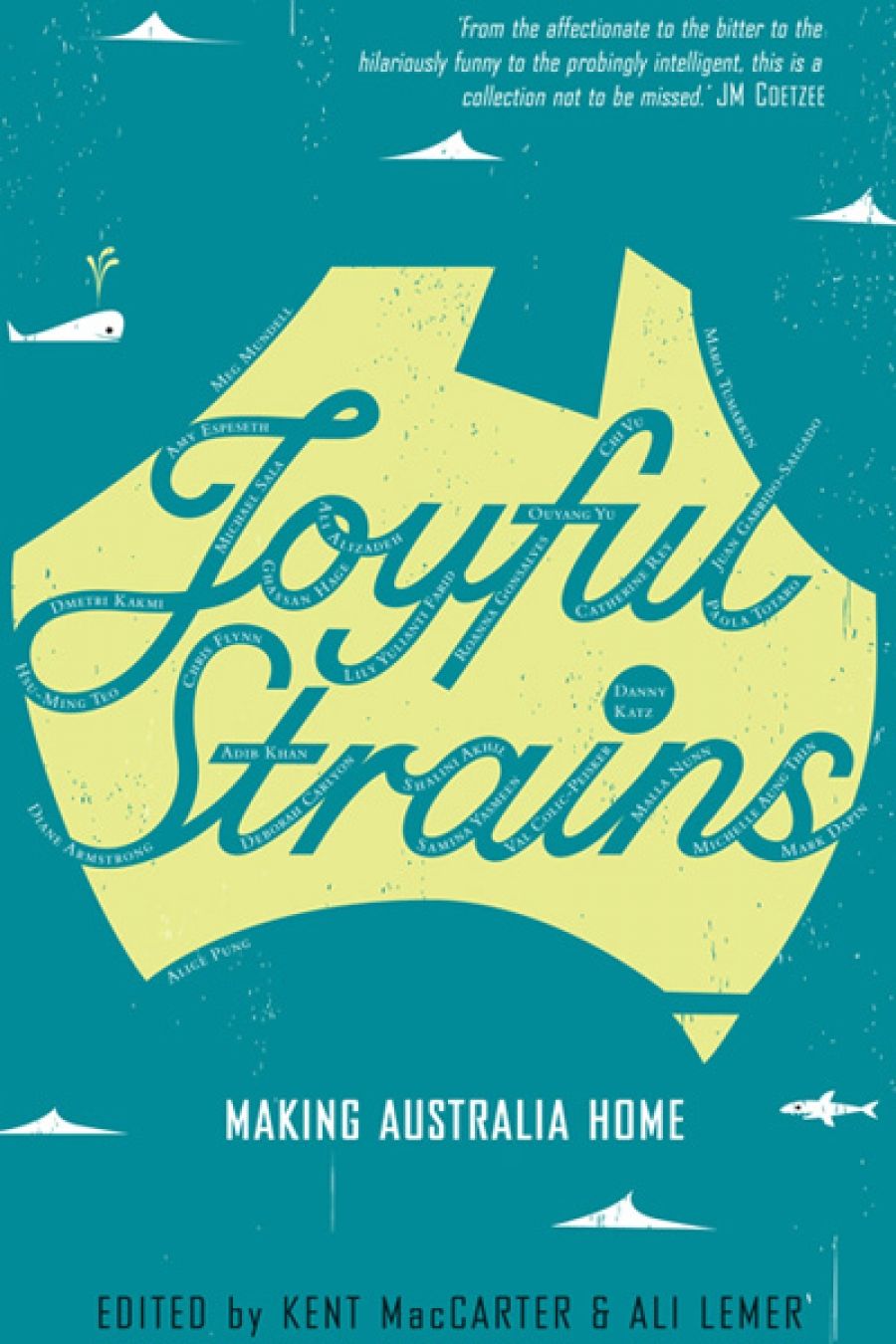

- Custom Article Title: Harry Brumpton reviews 'Joyful Strains: Making Australia Home' edited by Kent MacCarter and Ali Lemer

- Book 1 Title: Joyful Strains: Making Australia Home

- Book 1 Biblio: Affirm Press, $24.95 pb, 288 pp, 9780987308535

So says the Department of Immigration and Citizenship’s handbook Life in Australia (2007) – recommended reading for all provisional and permanent visa applicants. These are surprisingly stirring lines, but they are not quite joyful strains. That title belongs to a new Australia Day arrival, a compilation of twenty-seven biographical essays by immigrant writers. If Life in Australia is intended as a guidebook of sorts, Joyful Strains offers the tattered travelogues of those who have come to call Australia home.

There is much to be learned from these tales, not only about the immigrant experience, but also about how our national character comes across to others. Russian-born contributor Maria Tumarkin recalls ‘how it was to be constantly itching with bewilderment, to compulsively be doing “compare and contrast”, to start falling for this country, loving it, while remaining unreconciled to it’.

The turmoil of being out of place and the ways in which adjusting can inwardly split a person form the core of most of the memoirs. These strains can stretch a person nearly beyond endurance. But they are often also the signal convulsions of a personality’s parturition. Dmetri Kakmi likens the inward conflict between his Greek and Australian identities to schizophrenia:

Dmetri was familiar to me; I knew him well enough. Who was Jim? I did not know what to do with this half-Greek, half-Australian boy, and had to invent him from the ground up. This led to the creation of a malleable persona that could be made to fit the mood and circumstance. Jim was whomever he needed to be in order to survive;in time, his presence in Dmetri’s body led to an internalised schism.

Meanwhile, Irish native Chris Flynn (in one of the more comic entries, an antipodean counterpart to Clive James’s 1985 migratory memoirs Falling Toward England) likens this feeling to launching a new software system of the self – though not without ‘a few bugs in the new operating system that would linger for years to come, irrespective of hardware updates’.

For Hsu-Ming Teo, adjusting from Malaysia found an allegorical parallel in how her broken arm, slowly strengthening, healed after her arrival. Chi Vu goes even further in her conclusion. For Chi and her Vietnamese family, who arrived on an unreliable boat described in Conradian terms, cheating death had the same interior result as death itself: ‘It seems that some small part of me (and I assume of each member of my family as well) did die on our journey over ... when we next face the abyss, we already know of its fathomless darkness, its ceaseless horror.’

It is a feat to keep these nebulous themes aesthetically compact and more than a couple of engrossing experiences end too abruptly. Iranian native Ali Alizadeh’s intense portrait of the lovelorn outcast (there’s a great deal of childhood embarrassment and adolescent awkwardness in these pages, understandable if you multiply the standard pangs of growing up by the fraught process of assimilation) is just one that falls short simply by being cut short. Ghassan Hage, similarly, gets tangled in the ribbon he tries to wrap around the compelling experience of finding three fully grown trees that his Lebanese grandfather had planted in Bathurst, making a convoluted coda about the term ‘rootedness’, arriving at a theory he calls ‘supra-counter-colonialism’, that would have had Sokal skipping a few paragraphs.

Elsewhere the anthology’s major appeal can become its own handicap:the iterative recollections feel repetitive. For example, most travellers at some stage pine for their home cuisine, but as a recurrent theme this becomes stale.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics last year recorded a net gain of one migration every two minutes and twenty seconds. As Tumarkin notes in her essay, forty-four per cent of Australians are born overseas or have at least one foreign-born parent, making her ‘as statistically average as they come. Nothing to see here. Keep on moving.’

Still, to assume that these tales are irrelevant because they are common would be to forget some of the recurring paradoxes in our national self-regard. First is the idea that ‘Australia is a lucky country’, an idea that not only discards Donald Horne’s final and operative fragment (‘run by second-rate people who share its luck’), but that also somehow seems to lie alongside the equally ingrained but contrary idea that we are also a nation of battlers grown all the stronger in spite of our lean beginnings and internecine hardships.

Second is the blend of another two opposite aspects of the national spirit: our traditional bluff egalitarianism and how it has hardened into a new order of reactionary values.Many in Australia still subscribe to credos that celebrate convicts and underdogs, but these ideas do not necessarily translate into an easy acceptance of those struggling to start a new life here today.

By numbers and by climate, then, this relatively small but ethnographically varied group of writers has a dauntingly representative status. But that is probably the point: what this sample lacks in scientific stature, it makes up for in how sorely its kind is needed, and how surely it deserves its welcome.

Comments powered by CComment