- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Phil Brown reviews 'Belomor' by Nicolas Rothwell

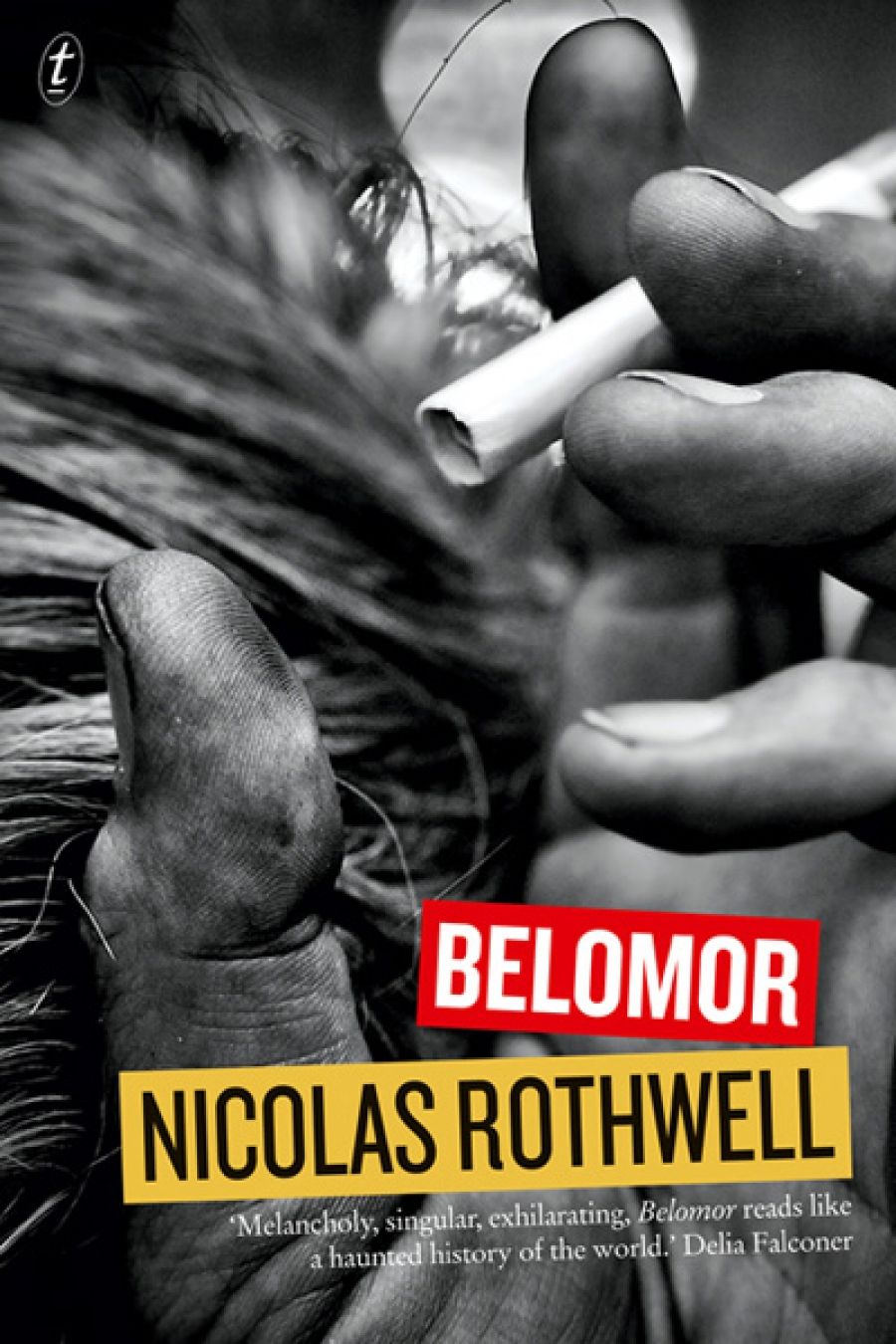

- Book 1 Title: Belomor

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 pb, 246 pp, 9781922079749

Part of this book is firmly rooted in Europe, where Nicolas Rothwell grew up. The other part is set in Australia, where he seems to have discovered himself. There is plenty of European content, much of it demonstrating a certain erudition, which is not nearly as interesting as the instinctual, more lyrical Australian material.

All the stories have Australian elements. As the author suggests, he is putting together ‘the jigsaw pieces of a shattered world’. Perhaps there can be no Australian epiphanies without loss and laments for the old world. For my money, though, the narrative elements that focus on Indigenous culture, art, and life in the Top End are much more engaging, while the European content can seem tired and contrived: too many passages about obscure artists, intellectuals, and architecture.

The sections dealing with Rothwell’s life in Darwin and his travels in the region are, however, riveting, verging on the mystical at times. It is hard not to think of the writings of Bruce Chatwin, in particular his celebrated book The Songlines (1986), and comparisons have been made before, particularly when Rothwell’s book Wings of the Kite-Hawk was published in 2003. Such comparisons are natural: both are outsiders, learned misfits, strangely drawn to notions of the Dreamtime. Rothwell is a Chatwin for a new generation, but he is not just passing through – he’s living and working in the place.

Rothwell is well known for his journalism in The Australian, and journos are famously jaded. There is a touch of that in Rothwell’s writing, but also something optimistic and redemptive. He seems to be on a personal odyssey as he traverses the north, journey by journey, character by character, in a way most of us never will. He is objective when he needs to be and segues into fiction with ease, though there is fact to his fiction. How much? And does that matter?

In the first story, ‘Belomorkanal’, we start off with the journeying of an eighteenth-century Venetian painter Bernardo Bellotto, who was inspired by Dresden, ‘with its spires and gleaming monuments’. As soon as I see the name Dresden all I can think about is Kurt Vonnegut and his novel Slaughterhouse-Five (1969), inspired by his experiences of the firebombing and destruction of that city during World War II.

Rothwell revisits that event and chooses the symbol of the Frauenkirche, a famous church in Dresden, as a motif for the resilience of European culture. ‘It was still the great sight to see in Dresden when I travelled there on a reporting trip, by train, in the company of a Polish peace activist named Berenika.’

Rothwell, who worked as a reporter in Europe, mixes reportage, history, travelogue, and politics in these stories. Like any good essayist (for these stories seem like essays at certain points), Rothwell knows the value of digression, thus reminding us of Robert Dessaix, though he lacks Dessaix’s sense of whimsy.

Straying from the point is often entertaining. And what is the point, anyway? Perhaps that life is a journey; that the author has seen much and knows much. But the history, the culture, the politics all seem ephemeral to the point of irrelevancy under the vast skies of the Australian outback.

‘Winfield Blue’ and ‘Mingkurlpa’, the last two stories in the book,get to the heart of the matter. Rothwell has a deep interest in and a profound understanding of Indigenous art. In ‘Winfield Blue’ (there’s that tobacco theme again), we meet Indigenous artists and travel to the remote art centre of Jirrawun run by the unhinged art dealer Tony Oliver, who greets the protagonist (Rothwell perhaps?) with a soliloquy riven with existential angst. This is a delicious passage, like something out of The Razor’s Edge, with a touch of Hemingway. When asked what went wrong, Oliver replies: ‘There’s nothing bad. It’s the turmoil of happiness that’s tearing me apart. Misery itself: that we know, that we can handle, of course – we’re always dealing with it … Defeat, failure, those are easy enough to bear: you adapt to them quickly. Acceptance, though, success: that’s a different story.’

It is the encounters with such characters in the Top End that are most fascinating in the final story, ‘Mingkurlpa’, in which the writer meets a woman in the Tiwi Islands. She is a European film-maker and our man is curious about her background.

‘What? You want me to tell you the story of my childhood? Here – now – in the darkness; it’s almost midnight; everyone on the crew’s exhausted: we’ve been working all day long.’

‘Why not?’ I said: ‘Reminisce. Bring back the past. You’re at a beach camp on the Tiwi Islands: probably you’ll never come back here again. Just talk, for no reason: don’t you find it sinister the way everything in our life has to lead somewhere? Tell a story – just for the darkness – for the night and for the heat. Anything – at random.’

In such passages Rothwell seems to be using fiction to outline his own philosophy of literature and life itself.

Comments powered by CComment