- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Subheading: Exploring the origins of an enigmatic tradition

- Custom Article Title: Ian Donaldson reviews 'Shame and Honor: A Vulgar History of the Order of the Garter' by Stephanie Trigg

- Custom Highlight Text:

Two photographs from the present book, caught by the British press in 2009, vividly testify both to the fun and to the difficulty of maintaining ancient ritual in the modern world. In the first, a widely grinning Prince Harry, one leg extended in parody of traditional marching style ...

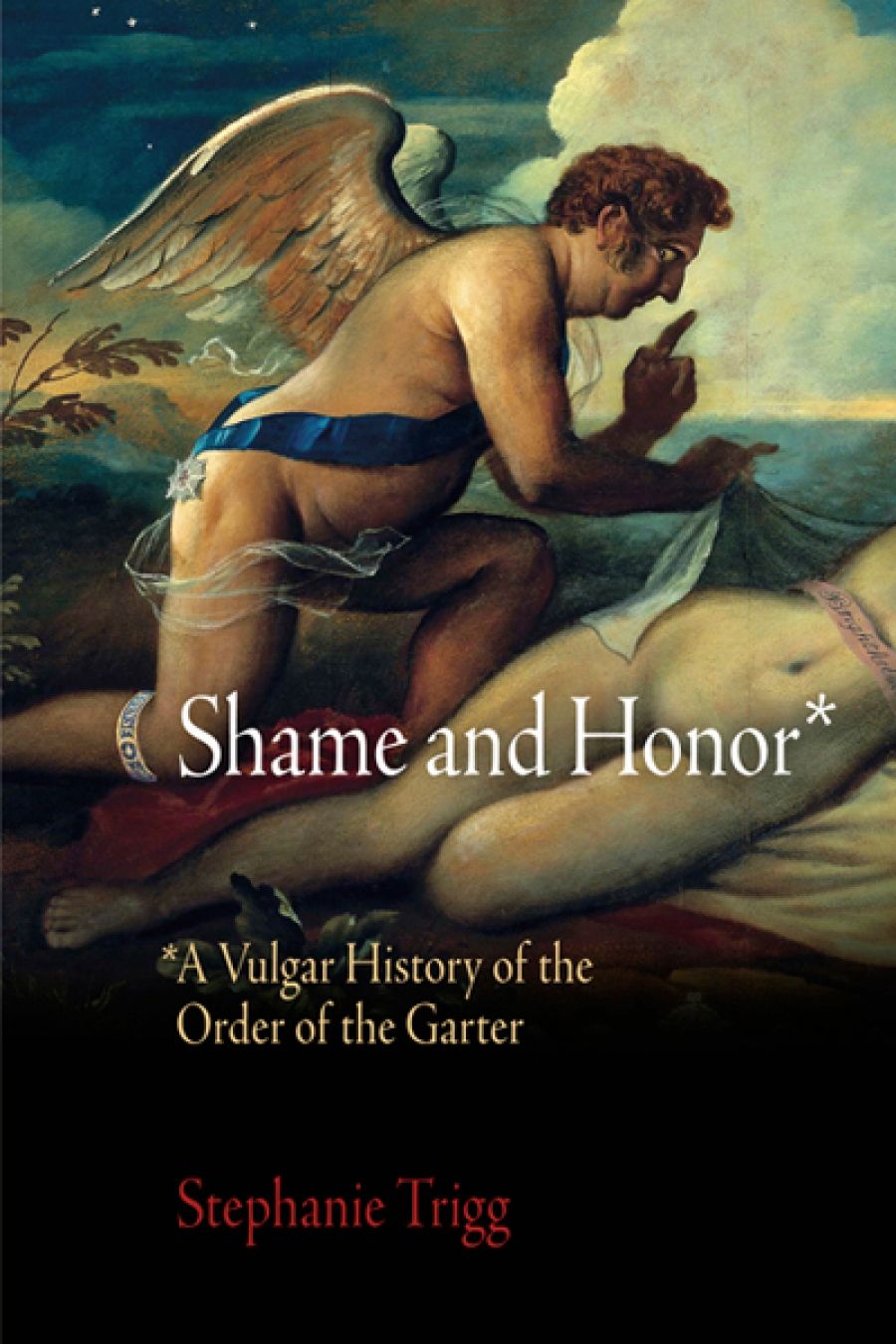

- Book 1 Title: Shame and Honor

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Vulgar History of the Order of the Garter

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Pennsylvania Press (Inbooks), $108.95 hb, 340 pp, 9780812243918

As Stephanie Trigg shows in this absorbing new study, the element of looming absurdity seems to have been present from the very initiation of the Order of the Garter, as its famously enigmatic motto, honi soit qui mal y pense, may suggest: ‘Shame upon him who harbours wicked thoughts’ – or alternatively, perhaps, depending on the sense of that troublesome ‘y’: ‘Shame upon him who thinks badly of this ritual.’ Edward III, so the foundational story runs, observing a garter fall from a lady’s leg while she dances, gallantly retrieves the item and ties it around his own leg, silencing the laughter of his courtiers by vowing to institute a new chivalric order dedicated to the Virgin Mary and to St George. Trigg makes good use of the earliest records – wardrobe accounts, literary texts, court anecdotes, speculations of chroniclers – in teasing out the possible context and significance of this richly layered story. Perhaps, as some scholars have  Prince William in his first Garter procession, 2009 © Press Associationconjectured, the embarrassment that Edward was attempting to head off was more serious than that caused by a fallen garter, for he had been accused of brutally raping his mistress, Alice Perrers, Countess of Salisbury, and may have hoped through the foundation of this new order to have partially silenced court gossip. Others have supposed that Edward devised the event in order to license the formation of an élite band of troops and boost his military interests in France. Neither of these conjectures, however, can now be convincingly proved or disproved, and the Order’s origins remain to this day something of a puzzle. For Trigg, ‘the very uncertainty of this myth and its truth claims are an important component of the Order’s mythic capital’, serving ultimately to enhance, rather than to diminish, its capacity for survival and renewal.

Prince William in his first Garter procession, 2009 © Press Associationconjectured, the embarrassment that Edward was attempting to head off was more serious than that caused by a fallen garter, for he had been accused of brutally raping his mistress, Alice Perrers, Countess of Salisbury, and may have hoped through the foundation of this new order to have partially silenced court gossip. Others have supposed that Edward devised the event in order to license the formation of an élite band of troops and boost his military interests in France. Neither of these conjectures, however, can now be convincingly proved or disproved, and the Order’s origins remain to this day something of a puzzle. For Trigg, ‘the very uncertainty of this myth and its truth claims are an important component of the Order’s mythic capital’, serving ultimately to enhance, rather than to diminish, its capacity for survival and renewal.

Shame and Honor offers a ‘vulgar history’ of the Order of the Garter more quizzical and conjectural in approach than other existing accounts of the Order, though no less serious in purpose. Alert to the oddities, lapses, and extravagancies that have overtaken the institution throughout its long history, Trigg aims to unravel its deeper significance, and the possible reasons for its survival into modern times. Drawing on the work of ethnographer Victor Turner, she notes that the story ‘answers to a ritual need to debase or humiliate a king, and to see the king’s majesty restored after that humiliation’. That may well be true, though Turner’s model of ritual debasement fails to explain who actually feels this supposed need and initiates the humiliation; whether the monarch is therefore its author or its victim. It thus rather fudges the questions it sets out to resolve: how exactly the ritual was first set in place, and how it is subsequently maintained. Better guesses, however, are soon to follow.

Rena Gardiner, King Edward III Picks up the Garter (1981) © The Dean and Canons of WindsorStephanie Trigg is a distinguished interpreter of medieval English literary texts who has turned her attention increasingly over recent years to the study of medievalism, fascinated by the afterlife – in Australia as elsewhere – of medieval ritual, and the strategic redeployment of archaic ceremony for political or social purposes. She offers here some fine readings of early literary works that deal with the Garter story (such as Wynnere and Wastoure and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight) and plausibly argues that ‘medievalist’ thinking may be pertinent to the origins of the Garter story, as well as to its later preservation. For Edward III himself, as she wryly notes, was already ‘a medieval master of medievalism’, a lover of courtly tournaments and Arthurian mythology, skilful at harnessing ancient rites ‘in the service of his own national ambitions and imperial aspirations’. Thus the Garter ritual may well have been, right from the start, a conscious exercise in archaism, a nostalgic recall of the noble days of the Round Table, a strategic manoeuvre to legitimate a similar present-day venture of Edward’s own devising. The mention of tournaments incidentally calls to mind an association that Trigg somewhat surprisingly fails to pick up. It was customary from earliest times for tourney participants to wear a single item of female attire – a glove, a ribbon, a scarf – in honour of some favoured lady: favours, as these tokens consequently came to be called. (In a later period, Sir Walter Ralegh’s mischievous young son Wat, with spectacular lack of decorum, took to wearing such items on his codpiece.) Was Edward, in tying the lady’s garter around his own leg, consciously following, if in a somewhat novel fashion, an already existing practice?

Rena Gardiner, King Edward III Picks up the Garter (1981) © The Dean and Canons of WindsorStephanie Trigg is a distinguished interpreter of medieval English literary texts who has turned her attention increasingly over recent years to the study of medievalism, fascinated by the afterlife – in Australia as elsewhere – of medieval ritual, and the strategic redeployment of archaic ceremony for political or social purposes. She offers here some fine readings of early literary works that deal with the Garter story (such as Wynnere and Wastoure and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight) and plausibly argues that ‘medievalist’ thinking may be pertinent to the origins of the Garter story, as well as to its later preservation. For Edward III himself, as she wryly notes, was already ‘a medieval master of medievalism’, a lover of courtly tournaments and Arthurian mythology, skilful at harnessing ancient rites ‘in the service of his own national ambitions and imperial aspirations’. Thus the Garter ritual may well have been, right from the start, a conscious exercise in archaism, a nostalgic recall of the noble days of the Round Table, a strategic manoeuvre to legitimate a similar present-day venture of Edward’s own devising. The mention of tournaments incidentally calls to mind an association that Trigg somewhat surprisingly fails to pick up. It was customary from earliest times for tourney participants to wear a single item of female attire – a glove, a ribbon, a scarf – in honour of some favoured lady: favours, as these tokens consequently came to be called. (In a later period, Sir Walter Ralegh’s mischievous young son Wat, with spectacular lack of decorum, took to wearing such items on his codpiece.) Was Edward, in tying the lady’s garter around his own leg, consciously following, if in a somewhat novel fashion, an already existing practice?

The long survival of the Garter ritual both mirrors and promotes the long survival of the British monarchy itself, as Trigg is aware. She draws profitably on the classic work initiated thirty years ago by Terence Ranger and Eric Hobsbawm on the invention of tradition, and in particular on David Cannadine’s study of the measures taken by the British monarchy in recent times to tweak and refurbish its public image through the addition of seemingly ancient, but in fact new-minted, ritual paraphernalia. The Garter ceremony, as Trigg shows, has been similarly refreshed and reinvented over the years, despite occasional resistance from its official custodians. Women have been involved in the ritual since earliest times, and since 1987, at the present Queen’s initiative, have been admissible to the Order as full Companions. Such changes bring their own small quandaries and challenges. On which part of the body, for  Sir Winston Churchill, 1954 © Bettmann/CORBISexample, should a lady Companion most decorously wear her garter? The Duke of Dorset’s mistress, Giovanna Zanerini – not quite a Companion, but at least a Companion’s companion – sported the Duke’s garter flamboyantly around her forehead. Others, prompted by Queen Victoria’s example, have tied theirs more modestly around the arm. And how, exactly, with the advent of the trouser, should a male Companion wear his garter? In another of the book’s well-chosen photographs, Winston Churchill smiles sheepishly as he steps from his car for a Garter ceremony in 1954 bizarrely clad in top hat, frock coat, breeches, and silk stockings, his garter secured in traditional fashion beneath the knee. More determinedly modern Companions such as Prince William choose to appear these days in trousers, with the garter slung stylishly around the neck.

Sir Winston Churchill, 1954 © Bettmann/CORBISexample, should a lady Companion most decorously wear her garter? The Duke of Dorset’s mistress, Giovanna Zanerini – not quite a Companion, but at least a Companion’s companion – sported the Duke’s garter flamboyantly around her forehead. Others, prompted by Queen Victoria’s example, have tied theirs more modestly around the arm. And how, exactly, with the advent of the trouser, should a male Companion wear his garter? In another of the book’s well-chosen photographs, Winston Churchill smiles sheepishly as he steps from his car for a Garter ceremony in 1954 bizarrely clad in top hat, frock coat, breeches, and silk stockings, his garter secured in traditional fashion beneath the knee. More determinedly modern Companions such as Prince William choose to appear these days in trousers, with the garter slung stylishly around the neck.

Trigg touches fleetingly on the rites of expulsion from the Order, and the larger question of shame in the pre-modern world. I wished there had been space in this richly suggestive book for a fuller discussion of these matters. Shaming rituals in earlier times tended curiously to mimic, through inversion, the rituals of honour against which their victims were thought to have offended. In the fifth book of Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, an errant knight is elaborately baffled, in an earlier sense of that term: hung, quite literally, upside down along with his arms and accoutrement and exposed to public display. In 1656 the Quaker James Nayler, having grown his hair and beard to suitable length, entered Bristol riding a horse, with his disciples casting their garments before him and singing ‘Holy, holy, holy’. Convicted, predictably, of blasphemy, Nayler was forced to repeat the entry in reverse, seated again on the horse but facing this time towards its tail, not its head; a humiliation his followers attempted unsuccessfully to redeem by claiming that Christ himself had been similarly humiliated after his entry into Jerusalem. ‘The extremes of glory and of shame, / Like east and west, become the same,’ wrote Samuel Butler in his mock-heroic poem, Hudibras, early in the reign of Charles II; and at moments such as these the two seemingly opposed concepts signalled in this book’s title appear indeed to converge and collapse into one. Shame and honour in the modern world are altogether more loosely associated than they were in earlier times. We still publicly honour the honourable, but are ashamed (it would seem) to shame the shameful. Throughout most of the Western world, rituals of public disgracing are now a thing of the past. Errant knights are no longer strung upside down on trees, but instead, quietly collecting their bonuses and dodging the paparazzi, depart discreetly through the rear of the building, preparing already for another life.

Comments powered by CComment