- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letters

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Absorbing letters from an ebullient queen

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is fitting to compare the longevity of the Queen Mother’s life with a magnificent hand-woven carpet running along a length of parquet down a torch-lit ancestral hallway: she was the embodiment of the twentieth century precisely because her life more or less spanned it. She was born on 4 August 1900 and (allowing for a bit of overhang into this century) died on Easter Saturday, 30 March 2002.

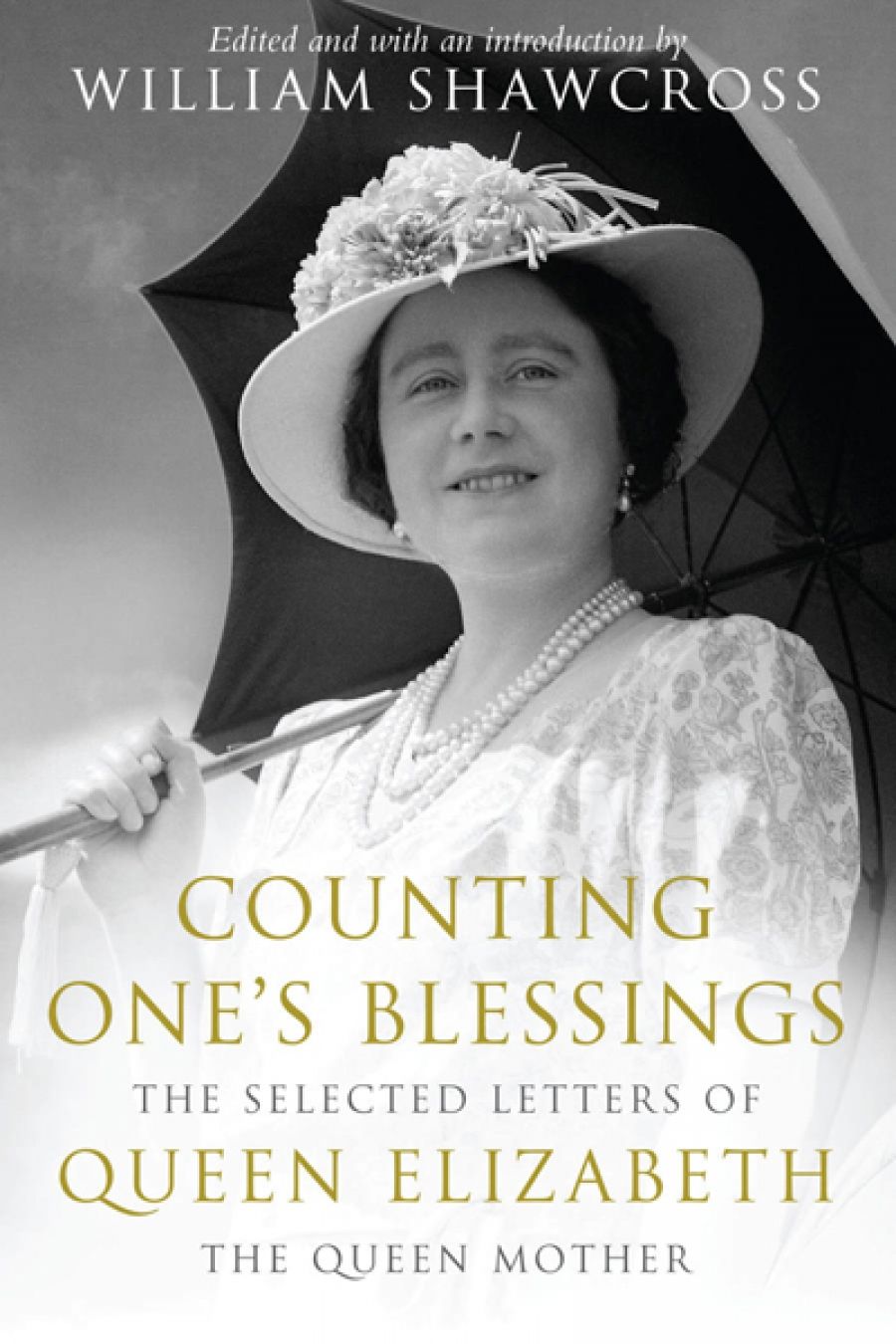

- Book 1 Title: Counting One’s Blessings: The Selected Letters of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $44.99 hb, 686 pp, 9780230754966

I like to think of the Queen Mother as a kind of Übergranny who was perhaps always older than anyone else, or at least seemed to be so in the memories of those younger than her – an ever-increasing breed. When she finally died, the other royals went up a notch in terms of seniority: just look at the Prince of Wales, who could be his father’s not-so-kid brother. But, then, Prince Philip, at ninety-one, is proving as indestructible as his late mother-in-law. As for the Queen, who is merely eighty-six, those Bowes-Lyon genes are as strong as ever. Age has not really wearied them after all.

The Queen Mother, though, had four lives in one: as commoner, duchess, queen, and her long twilight as a widow. As Her Majesty’s official biographer and now by-appointment mail-sorter, William Shawcross, points out, until she was twenty-two she was a private individual with no expectation of becoming a public figure. But then, in April 1923, she married the Duke of York (Bertie), second son of George V. Thirteen years later, after Edward VIII abdicated in order to marry Wallis Simpson, Bertie succeeded to the throne, Elizabeth by his side. After the king’s death in 1952, his widow became Queen Mother.

Detail from Sir Gerald Kelly, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II (1938–45)

Detail from Sir Gerald Kelly, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II (1938–45)

Shawcross’s 1000-page behemoth of a biography (2009) already quotes from the Queen Mother’s letters, many of which are stored in the royal archives, and it was tempting to wonder if he had wrung the dishcloth dry. On the contrary, Counting One’s Blessings is an extraordinary achievement that not only distils ninety-two years of letters into a manageable span, but also proves their writer to be possessed of an entirely original mind capable of passion, compassion, love, and harmony, and also an enduring and endearing wicked wit obviously embedded in the regal DNA since childhood. She loved the works of Damon Runyon and P.G. Wodehouse, so what more can one say other than what fun she must have been!

Let it be said that a goodly amount of Her Majesty’s correspondence is a well-shaken cocktail of aperçus and aphorisms, fuelled (as it were) by her legendary capacity for alcohol. In the early 1930s the Duchess of York was instrumental in the creation – as well as being the patroness – of a secret group, the Windsor Wets, whose motto, Aqua vitae, non aqua pura, was supplemented with a secret sign: ‘to raise the glass to other members without being seen by the disapprovers!’ This was a triumphant recovery from the teetotal scare of 1925, when the duchess wrote to her husband, ‘the sight of wine simply turns me up! Isn’t it extraordinary? It will be a tragedy if I never recover my drinking powers.’ A magnificently pithy footnote says simply: ‘The duchess was pregnant with her first child, Princess Elizabeth. The aversion to alcohol passed.’

The Queen Mother was also a first-class grudge-bearer. For example, while she never forgave her brother-in-law, the Duke of Windsor, for the abdication, she did remain fond of him (only just, but probably because of the king), and they exchanged cordial letters. Her real scorn was reserved for the Duchess of Windsor. An extract from a letter to Prince Paul of Yugoslavia, dated 2 October 1939:

David’s visit passed off very quietly. He and Mrs S stayed with Baba & Fruity Metcalfe, & they have now returned to France, where let us hope they will remain.

I think that he at last realizes that there is no niche for him here – the mass of the people do not forgive quickly the sort of thing that he did to this country, and they HATE her! D came to see Bertie, and behaved as if nothing had EVER happened – too extraordinary. I had taken the precaution to send her a message before they came, saying that I was sorry I could not receive her. I thought it more honest to make things quite clear. So she kept away, & nobody saw her. What a curse black sheep are in a family!

But this was also the woman whose dogged support of her husband, in public and in private, helped George VI seek advice over his stammering affliction (as documented in the 2010 film The King’s Speech), and, indeed, played a vital role in helping a nation come to terms with a terrible, destructive war simply by being there and never leaving her husband’s side.

At the heart of the conflict, writing in 1941 from Blitz-torn London to her sister, the Queen said: ‘I am still just as frightened of bombs going off as I was at the beginning. I turn bright red and my heart hammers, in fact I’m a beastly coward but I do believe that a lot of people are, so I don’t mind … Tinkety tonk old fruit, and down with the Nazis.’

More than a few of the letters are in this half-comic vein; those looking for deep historical, political, and social insight will perhaps be disappointed. But, then, the Queen Mother was not that kind of person, and nor did she ever intend her correspondence to be made public. As such, this book has its ephemeral side. Yet I found it curiously irresistible. Shawcross himself says, ‘Her words danced on the page, teeming with vitality, ebullience and optimism.’ So it proves, in abundance.

Comments powered by CComment