- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the art world, the question of who shapes public taste is a perennial favourite. Magazines like to rank the heavyweights. Last year’s ArtReview’s Power 100 included an assortment of global dealers and collectors; Ai Weiwei and Pussy Riot made it too. While such ladders of influence invariably include museum staff and art historians, it is clear that Jenny Holzer’s aphoristic ‘Truism’, Money Creates Taste, was prescient.

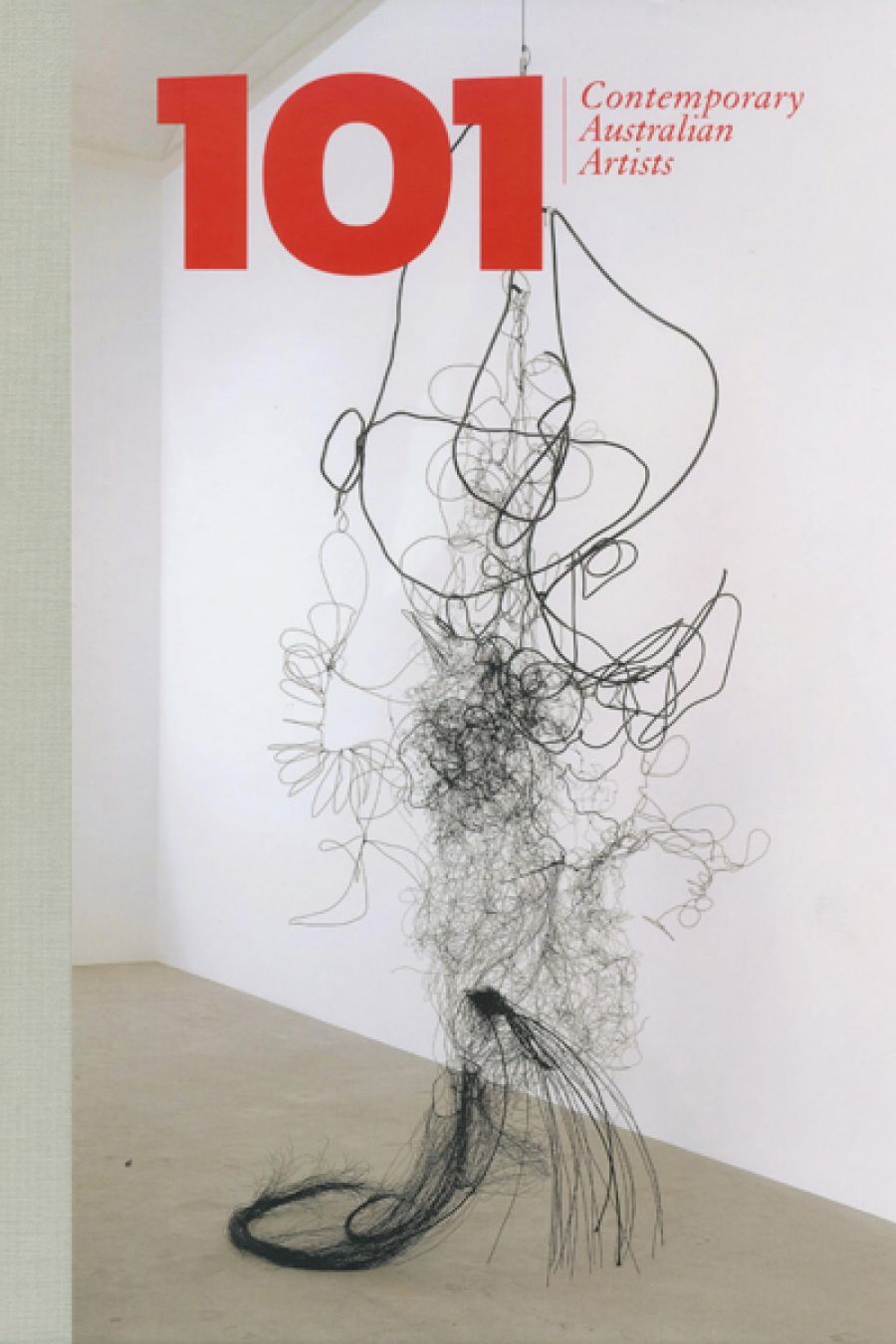

- Book 1 Title: 101 Contemporary Australian Artists

- Book 1 Biblio: National Gallery of Victoria, $49.95 hb, 237 pp, 9780724103621

In the public eye, fanned by an ever-predicable media, price is deemed to be a measure of artistic importance. Museums have long suffered for doing what they do well: exercising curatorial discernment early in artists’ careers, which emboldens those with the wherewithal to buy, only to leave museums floundering in their wake, unable to compete with the consequences of their original judgements. It is fair to say that art museums provide the intellectual backbone for much commercial activity. The frequent lament of museums is that they are seldom part of the top-end primary and secondary markets when masterworks are up for grabs.

There are times when respected commentary fails to dent reputations. Robert Hughes railed against Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, and Jean-Michel Basquiat, but their prices went through the roof. Unrestrained ambition can find its own market niche: Charles Saatchi and his support for the coterie known as Young British Artists is an obvious example of this. Too much money is involved, and this seems to lead to a suspension of critical reason. But that’s not going to change – ever.

Rosemary Laing, Welcome to Australia (2004)

Rosemary Laing, Welcome to Australia (2004)

In Australia, a small number of private collectors (often connected with major public galleries) are prepared to pay large sums for contemporary art. Do Australian public galleries shape broader taste and collector conduct? Does it really matter? After all, most of us don’t live such rarefied existences – if the museum’s influence is purely humanist idealism, isn’t that enough? Perhaps, but that’s not how it works.

101 Contemporary Australian Artists (exhibition and catalogue) marks the tenth anniversary of The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, at Federation Square, and the establishment of the Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists (VFLAA). After a decade opinions about the building remain divided; some see it as a contemporary expression ideally suited to the art of our time (the book argues this case); others view it as an architectural disaster littered with design affectations.

Melbourne was the centre of modernism in Australia. In the past three decades the NGV has been accused of failing to fulfil its role in dealing with the contemporary and experimental. The book’s introduction, in seeking to mollify that perception, becomes somewhat defensive, then declaratory, about its relationship with contemporary art. The works featured in the book range across media and genres: painting, fashion, photography, sculpture, jewellery, printmaking, video, drawing. Aboriginal art is interleaved into the whole account of contemporary art. Younger artists are presented alongside those who have made lasting contributions. The catalogue is democratic without being precious in its selection or seeming obliged to tick the right boxes. For an institution that can boast one of the finest collections of British art on the planet, the works and artists in 101 have their origins in a range of cultures and avoid any sense of hackneyed ‘Australianness’.

Simon Terrill, Huddle (2007)

Simon Terrill, Huddle (2007)

The essays are informative, some offering more confident interpretations than others. The twenty contributors all work for the NGV. We are spared all-too-prevalent clichés like ‘transgressive’, ‘multiple layers of meaning’, and ‘blurring the boundaries’ (well, there is one), and ‘identity’ isn’t left hanging as some kind of amorphous condition without explanation. This is a book for the general public, not one addressed to specialists. Thankfully, art that deals with political issues is more sophisticated than sectarian zeal and a call for action.

The introduction states that the ‘VFLAA is a work in progress’ (fair enough, too: most collections of the art of our own time are), and ‘it is not possible, indeed, desirable to draw definitive conclusions about the recent history of Australian art or across Australian art in general’. After acquiring 380 works by 144 artists in a decade, some authoritative conclusions might have been reached, as distinct from descriptive summaries of diverse interests. The book’s cool design leads us to assume that this is more than an articulate snapshot souvenir. Each artist is given a double page, with the text and image facing each other. (The design is pleasingly minimalist, but you really struggle to read the caption information, which is printed in soft grey and in something like eight point.)

Predictably, some will grumble at the inclusion of certain artists and the absence of others. I thought two or three of them had exhausted their fifteen minutes before the clock even started. But this is inevitable with books of this nature. Despite any definitive argument on the condition of Australian art over the past decade, the offer of 101 works and essays must be taken as an authoritative text. When a pre-eminent institution like the National Gallery of Victoria publishes its curatorial meditations, we take notice.

Comments powered by CComment