- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Over the last few years, issues associated with underdevelopment in Aboriginal Australia have been widely canvassed in the mainstream press, led by the likes of Noel Pearson, Marcia Langton, and Peter Sutton. This new edited volume adopts a somewhat different approach to Aboriginal development, focusing on Indigenous involvement in natural resource management around Australia.

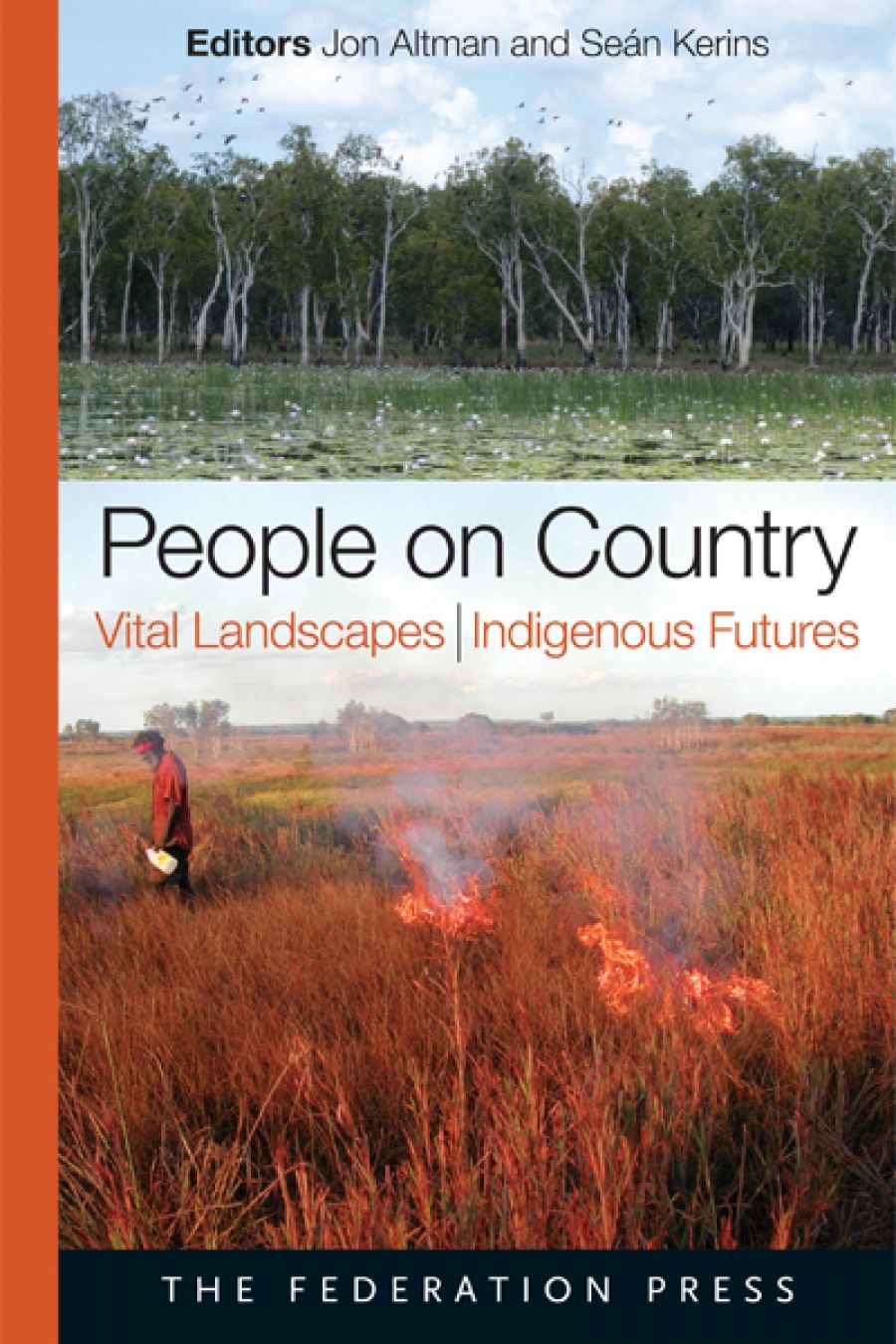

- Book 1 Title: People on Country

- Book 1 Subtitle: Vital Landscapes, Indigenous Futures

- Book 1 Biblio: Federation Press, $39.95 pb, 272 pp, 9781862878938

Jon Altman introduces the collection with a personal epiphany. As he documents, over the last forty years of land rights and native title claims, a massive ‘Indigenous estate’ has developed, amounting to more than 1.7 million square kilometres of Australia. It was at a conference in mid-2006 that the ecological significance of this Indigenous estate first became clear to Altman when he overlaid a Land and Water Australia resource atlas over a template of this estate, revealing that the most ecologically intact parts of the continent are largely Aboriginal-owned or -controlled. In 2006 this estate was managed by Aboriginal people under a scheme called Caring for Country. However, since 2007 and the creation of the program ‘Working on Country’, this land has begun to be managed in an increasingly bureaucratic way. Today there are approximately 660 Aboriginal rangers employed under the program, at eighty sites across Australia, with an estimated cost of $240 million (2007–13).

With contributions from twenty-seven people broadly grouped into university-based researchers (Part One) and community-based ranger groups in the Northern Territory and New South Wales (Part Two), People on Country: Vital Landscapes, Indigenous Futures presents a partial review of this program, as well as a kind of manifesto for environmentalism as a means of Indigenous development: promoting healthy landscapes and healthy lives through working and living on country.

All too often, as the editors argue, debate about Aboriginal development in regional and remote Australia is restricted to a focus on mainstreaming: ‘Closing the Gap’ between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians at the expense of possibilities for different ways of living. This collection seeks to challenge this orthodoxy. It calls for greater support for ‘hybrid’ economic futures, whereby some people’s desire to live in small, isolated settlements far from ready access to the real economy might be supported by government and non-government funding. ‘Country’ needs people, the contributors argue, just as Aboriginal people might be said to need ‘country’.

Part One offers perspectives from five academics at the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research in Canberra. Seán Kerins, an anthropologist, identifies the many successes of Aboriginal ranger programs, but worries about the prospective ‘mainstreaming’ of Working on Country within the Australian Government’s Caring for our Country Business Plan (2012–13). Emilie Ens, a plant ecologist, similarly expresses concern that Working on Country might become dominated by what she sees as ‘western ideology and approaches, with tokenistic Indigenous involvement or labour’. Instead, Ens calls for a ‘two-way’ approach that seeks to combine Aboriginal knowledge with ‘western’ science, notwithstanding practical challenges relating to the collection of reliable ecological data by those with low numeracy and English literacy skills. Following Ens, Geoff Buchanan and Katherine May take such ‘two-way’ thinking even further, calling for greater support for what they call ‘Indigenous economies’ and arguing that money should be spent to subsidise the harvesting of bush foods through Aboriginal fishing, hunting, and gathering. Bill Fogarty, similarly, calls for schools in regional and remote areas to play a greater part in promoting ‘learning through country’ by taking children out of the classroom and into the bush to acquire ‘customary harvesting skills’ like catching turtles.

Readers may respond cynically to these arguments. Certainly, they sit uneasily alongside views advanced by Pearson, Langton, Sutton, and others that Aboriginal people in regional and remote areas might aspire to equivalent outcomes with those in cities, and indeed with non-Aboriginal people. Some readers may also be put off by the polemical tone of some contributions, which manifest the authors’ distaste for what they call ‘neo-liberalism’. Janet Hunt’s concluding chapter presents something of an exception, offering a more balanced view of the successes and failures of an Aboriginal ranger group in north-west New South Wales.

Part Two – in many ways more interesting – offers an insight into the attitude of Aboriginal people to some of the policy developments debated in Part One. It offers perspectives from different parts of Arnhem Land, by the Dhimurru, Yirralka, Warddeken, Djelk, and Yugul Mangi rangers. Each group documents its achievements, repeatedly stressing the links between country and people, culture, and language. While success in managing environmental problems like feral animals and invasive weeds is clearly a source of pride, involvement in ranger programs seems to mean more for each contributor than simply environmentalism. As Victor Rostron, Wesley Campion, and Ivan Namarnyilk from the Djelk rangers (facilitated by Bill Fogarty) state: ‘[A]s well as Djelk being about the environment, we have also always had a focus on our social role within the community; looking after country and looking after people go hand in hand for us.’

These connections are also stressed by contributions from ranger groups outside Arnhem Land. For example, Jack Green and Jimmy Morrison (facilitated by Seán Kerins), from the south-west Gulf of Carpentaria, argue passionately against government ‘dragging us off our homelands and backinto town, yardin’ us up like cattle’. These senior men call for help from government to grow from the bottom up, to get things started:

In the future we’d like to see ourselves running our own organisations, being in full control and not being reliant on people with no understanding of our culture and law … We want our own enterprises that help us remain living on country and caring for it and keeping culture strong, just like our old people taught us.

Tanya Patterson, from north-west New South Wales (facilitated by Janet Hunt), similarly calls for recognition and help: ‘we want to be providing more employment, and stability of that employment, for Aboriginal people.’ Taken together, these chapters provide a compelling illustration of one success of the Working on Country program: giving a voice to Aboriginal people in regional and remote areas, even as they highlight continuing challenges experienced by each group in trying to get people in government to listen to them.

As Altman argues, it is doubtful that those who began the long journey for Aboriginal land and native title rights some forty years ago envisaged a future where almost a quarter of the Australian continent was under Aboriginal ownership or control. This fact poses enormous challenges for the future in the face of threats from feral animals, invasive weeds, fires, and climate change. People on Country begins a conversation about how these challenges might best be met and suggests that policy discussions should be balanced with more direct accounts of the successes and failures of Working on Country. While some readers may be sceptical about the academics’ call for environmentalism as a means of alternative development, Aboriginal involvement in natural resource management programs is one of the few bright outcomes of recent policy shifts affecting Aboriginal people in Australia. As the contributors argue convincingly, Working on Country should continue.

Comments powered by CComment