- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Reading through a hundred years of Poetry, week after week of issue after issue after issue, some forty thousand poems in all, Don and I, when we weren’t rendered prone and moaning, jolted back and forth between elation and depression.’ So Christian Wiman writes in his introduction to this elating, and never depressing, new anthology celebrating one hundred years of Poetry Magazine. Bear in mind that he and fellow editor Don Share did this while continuing with their day jobs as editors of the magazine, which receives some one hundred thousand submissions a year, and you will have some idea of the task they undertook.

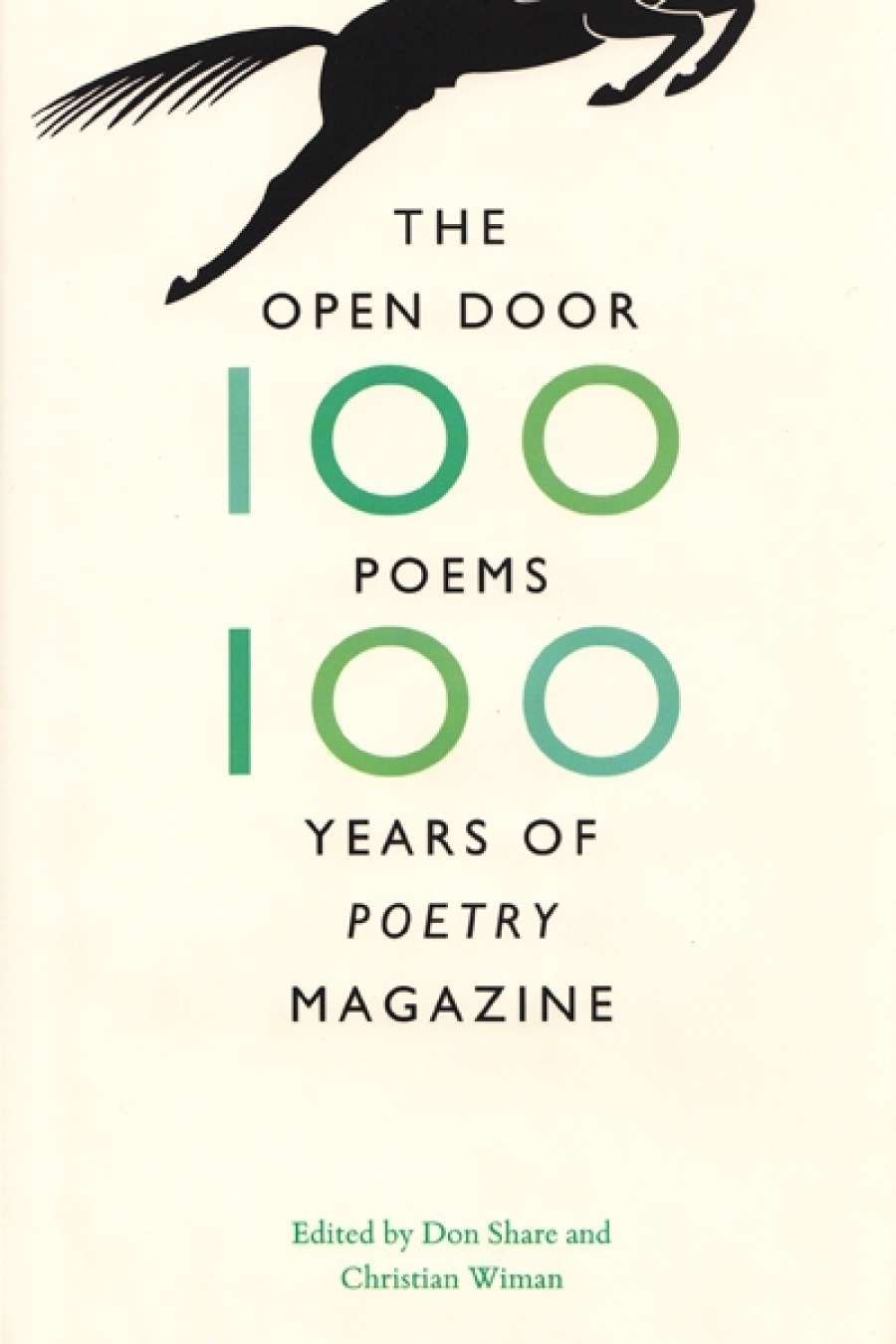

- Book 1 Title: The Open Door: One Hundred Poems, One Hundred Years of Poetry Magazine

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Chicago Press (Footprint Books), $29.95 hb, 222 pp, 9780226750705

One hundred poets, one hundred poems. How did they do it? Wiman goes on to say that he and Share decided to ‘focus on poems, not names’, ‘with an eye out for the unexpected – the one-off masterpiece … the little known gem’.

There are some very famous names and poems, as you would expect, perhaps none more so than ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’; but not all the big names are represented by their big poems. Though Wallace Stevens’s ‘Sunday Morning’ was published in Poetry, it is by the glittering little ‘Tea at the Palaz of Hoon’ that he is represented. W.H. Auden is here with ‘The Shield of Achilles’; W.B. Yeats, who concludes the anthology, with ‘The Fisherman’, with its bracing last lines: ‘… Before I am old / I shall have written him one / Poem maybe as cold / And passionate as the dawn.’

But the great pleasure of the book is the surprises, poems that I, at least, mostly did not know, whether by familiar or unfamiliar poets. Here, a few will have to stand for many. There is Belle Randall’s stunning ‘A Child’s Garden of Gods’ (‘The summer that my mother fell / Into the hole that was herself’), with its vision of a mother’s mental collapse from the viewpoint of the uncomprehending children; and Kay Ryan’s ‘Sharks’ Teeth’: ‘… An hour / of city holds maybe / a minute of these / remnants of a time / when silence reigned, / compact and dangerous / as a shark. Sometimes / a bit of tail / or fin can still / be sensed in parks’; William Matthews’s ‘Mingus at the Showplace’: ‘And I knew Mingus was a genius. I knew two / other things but they were wrong, as it happened’; Don Paterson’s ‘The Lie’, in which the ‘lie’ is both a mental state and an actual child in a basement (‘The dark had turned his eyes to milk and sky / and his arms and legs were all one scarlet sore’); Adrian Blevins’s ‘How to Cook a Wolf’, ‘the dumbstruck story of the American female’: ‘… until your head is stuffed with a pining for diapers / … and Ajax and Minwax Oh.’

One point which Wiman does not directly address in his introduction is the order of the anthology. Most anthologies are arranged chronologically, but in this case that would have been boringly literal-minded: a sort of mini-tautology. What they have decided on – and, when you think about it, it was the only possible choice – is an order that is no order, an organic arrangement in which poems from widely separated years rub shoulders in such a way that they spark charges of similarity and contrast off one another, or create small constellations.

So, George Starbuck’s ‘Of Late’, from October 1966, a ‘bizarre rhetorical shriek’ written during the Vietnam War (‘And Norman Morrison, Quaker, of Baltimore Maryland, burned what he said was himself’) is preceded by Isaac Rosenberg’s ‘Break of Day in the Trenches’ from December 1916 (‘Droll rat, they would shoot you if they knew / Your cosmopolitan sympathies’), and followed by Randall Jarrell’s ‘Protocols’ from June 1945, whose bracketed subheading ‘(Birkenau, Odessa)’ gives you all the clues you need.

The introduction in itself contains great food for thought, comprising twenty-one short sections, ‘Ways to Read a Century’, dealing with subjects such as modernism itself, and its legacy, whether there is a public for poetry, the role of craft and technique, the fact that the enjoyment of poetry entails ‘letting yourself experience things you do not understand … the textures and rhythms of verse’. One cautionary note: to be good at reading poetry we need to keep the capacity of surprise. ‘It’s easy to become so mired in our likes and dislikes that we can no longer recall that person who once responded to poems … without any preconceived notions.’ We need to discover those poets, I seem to recall Chris Wallace-Crabbe saying somewhere, who can ask the questions we cannot. This anthology, by its range and variety, should awaken that capacity and pose those questions for most lovers of poetry.

Interspersed throughout the anthology are snippets of prose drawn from the ‘Comment’ section of the magazine, or from letters. They create small pauses of reflection among the poems, touching, usually tangentially, on their preoccupations. Sometimes they contradict each other: ‘Don’t be descriptive,’ warns Ezra Pound, while W.S. Di Piero declares, ‘Good descriptive poems are like perfumes made tactile.’ Poems by Geoffrey Hill and Richard Wilbur eloquently rebut Pound with astonishing descriptive passages. The last stanza of Wilbur’s ‘Hamlen Brook’ could almost describe poetry itself:

Joy’s trick is to supply

Dry lips with what can cool and slake,

Leaving them dumbstruck also with an ache

Nothing can satisfy.

Comments powered by CComment