- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In Alan Wearne’s new collection, his not-quite-self-appointed role as chronicler of Australian mora et tempores continues, more overtly than before. Prepare the Cabin for Landing pays homage to the Roman satirist Juvenal and his eighteenth-century heir, Samuel Johnson. Both shared what Wearne describes as ‘that combination of bemusement, annoyance, anger and despair to which your country (let alone the country of mankind) can drive you’.

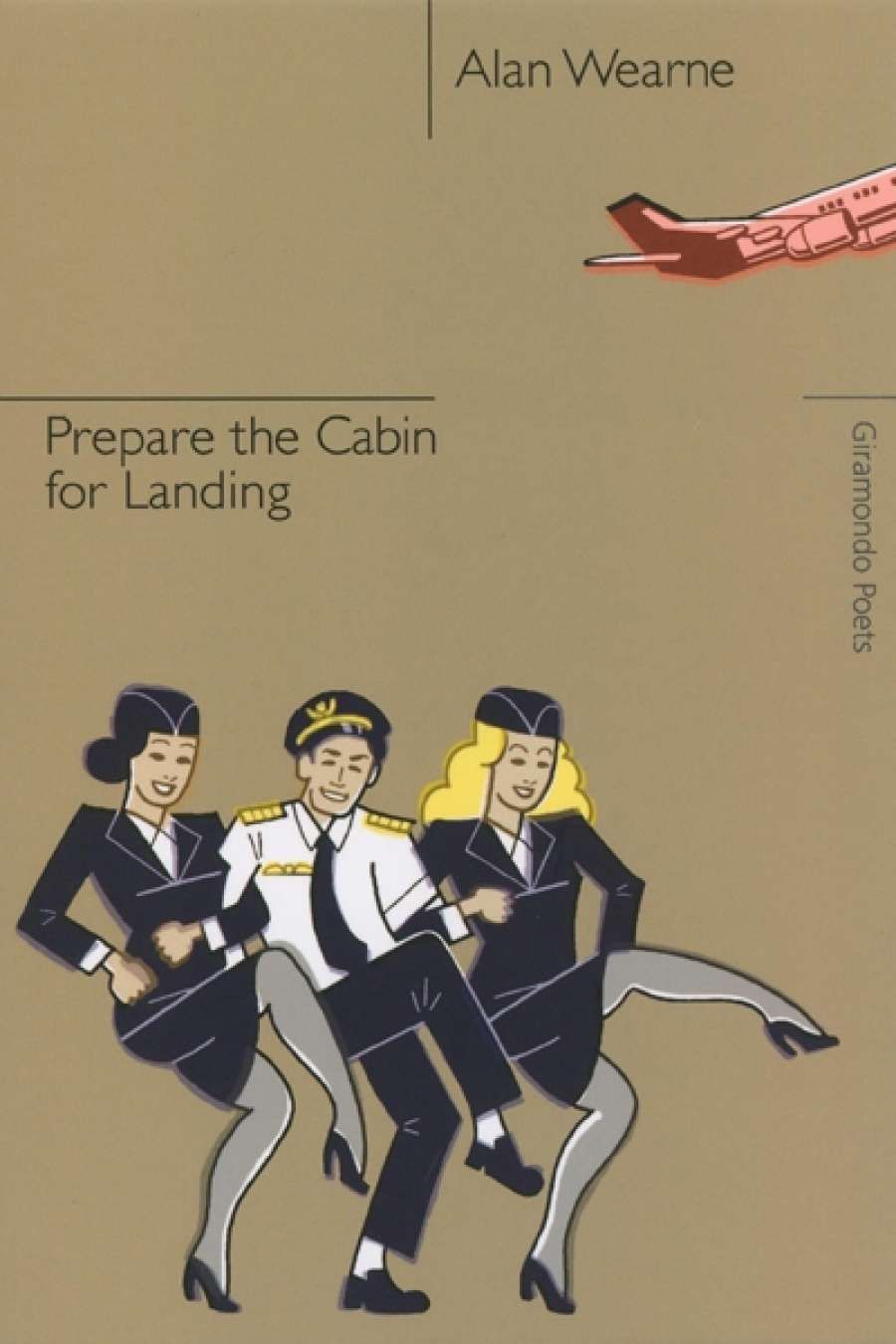

- Book 1 Title: Prepare the Cabin for Landing

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $24 pb, 106 pp, 9781920882945

What is satire, anyway? N.S. Gill, an Internet classicist (cue a Wearne grimace), defines Roman satire as ‘personal and subjective, providing insight into the poet and a look (albeit, warped) at social mores’. As good a definition as any, and one that suits Alan Wearne’s book to a T. He seems, though, in his rumbling, rambling, stone-kicking way, more Johnson than Juvenal, and the more he rhymes the more eighteenth century he appears.

‘All these young Australianists’, for example, is a broad, vaudevillian sally aimed at all those intellectually charged artistic tyros that Australia disperses around the world on fellowships or to workshops, conferences, and festivals:

I am Janice Y. Wilde critic and poet / whilst he (my ‘partner’) is the critic, essayist, novelist and naturally / poet Ted Tucker / Euro-conferencing doubtless gives one, though I’m sure you know it, / mind-enhancement, network-enlargement and dollops of let’s-just- / call-it succour.

Plenty there to be going on with (who could he have in mind?), but, as usual with Wearne, it’s just the start. Most of the poem is rhymed in a loose-limbed but exact way, until the middle section, when he calls in the metric equivalent of an airstrike: ‘We reckon you can’t beat a system / that buys time to travel and write, / the advantages bloom so we’ll list ’em / for edification, delight.’ Wearne’s delight is obvious: it’s so cheerful the late Ian Dury could have written it.

He is just as rousing when romping through the lives of North Carlton boomers Ali and Bob, in ‘Dysfunction, North Carlton Style’, who are everything you would expect them to be and have the satirically inevitable turncoat materialist children. Wearne draws quickly and broadly, more in the style of Gillray or Rowlandson than of an argumentative satire: ‘An architect, Bob possessed mighty dimensions: / a proud blooming afro, a grand frontal lobe. / He designed half of North Carlton’s extensions. / She lectured in Ethics, out at La Trobe.’

All this is great fun, and self-aware fun at that: but Wearne works harder and does better when he deals with particulars. The rhyming triplets in ‘The God of Hope’, which recounts in oblique fashion the story of the Nugan Hand Bank in the 1970s, are precisely syncopated, making the eye and ear pause long enough to comprehend a deliriously plausible tale of excess and corruption.

Wearne is present in these opening poems largely by inference, in his style, in the language of the characters: but at the heart of the book, in the forty-odd pages of ‘Operation Hendrickson’, he is right out in the open. In a Wearnian remix, we are once again back in a lowly high school in a suburb in the 1960s, with our protagonist Bob Hendrickson and his motley group of mates, as they fall through life. ‘Nasho’, drugs, pointless, existential deaths, all bounce off Hendrickson’s faintly bathetic anti-heroism, until he and ‘Wearney’, the intellectual of the bunch, with his rag called ‘Proper Gander’, are the last two standing, and Wearney ruefully accepts the role of Henn’s biographer.

For the most part it is unrhymed and, though one feels at times as if the world has stopped forever somewhere between 1963 and 1978, it is all portrayed with complete conviction, as if there’s no hindsight to spoil things. One night Hendrickson meets up with his old schoolmate, Vietnam veteran Johnny:

He gave me one small tab and that night / I was walking north where Punt Road overpasses / Dandenong Road at St Kilda Junction, / pushing myself into the warm spring air as it kept folding around me. I was so pleased, / nothing would stall wherever I went.

This is what is important: not the ills of the world and the vexations of society, but friendship. In the book’s final poem, ‘The Vanity of Australian Wishes’, this is even more evident. It self-consciously shadows Johnson’s ‘The Vanity of Human Wishes’, which, in its turn, imitated the Tenth Satire of Juvenal, and cuts a wide swathe through Just About Everything Since The War, with Hogarthian caricatures popping up at every turn. Is that Hawkey? That’s definitely Howard! A footy player: but which one?

The ‘bemused despair’ Wearne is drawing on feels a bit forced here, almost making a satire of the satire –a postmodern exercise one wouldn’t usually suspect him of undertaking. We soon find out why: around all this he has interwoven the deaths of gangster Alphonse Gangitano and Wearne’s great friend, the poet John Forbes: ‘John at fourteen, intending to be a poet / told himself how that would be the finest way / to spend a lifetime. We are glad he did. / He was our conscience, the voice announcing / ‘Near enough isn’t even remotely near enough.’

Now we have it. All the book’s dialectical clash of rhyme and distemper has been in the service of this very well-tempered truth: Alan Wearne is not a Johnson, but a Boswell, and a fine one too.

Comments powered by CComment