- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

By its title, Tales from the Political Trenches promises reportage from the front line, eyewitness accounts of what really happens in the hidden zones of the political battlefield. The tales told here follow a rollercoaster sequence of political events: the meteoric rise of Kevin Rudd, Maxine McKew’s triumph over ...

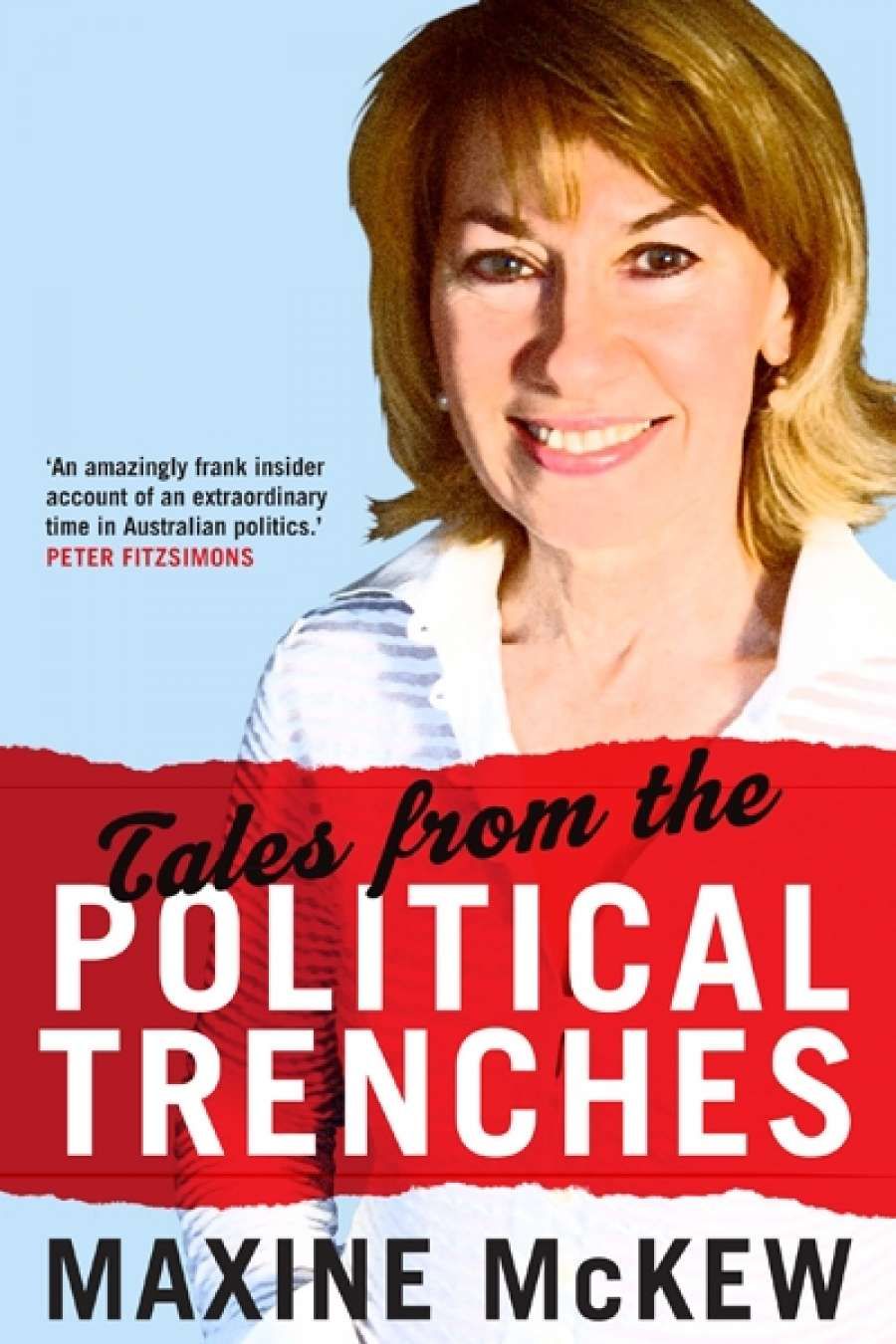

- Book 1 Title: Tales from the Political Trenches

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $29.99 pb, 256 pp, 9780522862218

The larger dramas of power and government take time to stabilise in the public consciousness, and this particular sequence of events is still churning. There are high political stakes in the way the narrative is presented. The Gillard government remains balanced on a knife-edge, and Gillard’s own standing in the polls is precarious. Why does McKew need to come forward with her version of the story at this particular point? By her own account, she didn’t start work on the book until late 2011, so the whole process of writing and publication has been fast-tracked.

It is traditional for leading political figures to publish their autobiographical reflections with some retrospective distance, but increasingly, it seems, publishers want to produce books that will sell for their catalytic appeal as game-changers in the steerage of public opinion on current issues. Bob Carr is reportedly working on a book about his adventures in Australian foreign policy, taking notes between meetings. Lindsay Tanner drew fire from ALP colleagues last year for the scathing critique of his own party in Sideshow, at a time when the hung parliament was hanging by a thread.

This phenomenon of book-driven politics is in its own way quite disturbing. There is a correlation between authorship and authority that lends a special clout to the book as a form of public communication; it involves a longer and deeper commitment than an article or essay, and implies that there is an attempt on the author’s part to offer a definitive overview.

In her opening chapter, McKew describes some encounters with Paul Keating, who is one of her mentors. He urges her to focus on ‘the contest of ideas’ in Canberra. He inspires her with a vision of how politicians can change the world, and plants in her mind the maxim that ‘there are two types in this world, voyeurs and players’. From this, she derives her own equation: the voyeur is the journalist and the politician is the player. When she makes the move to cross the divide, leaving her job as one of the ABC’s leading current affairs presenters to take on the challenge of standing for Bennelong, she is driven by the conviction that she is entering the main game. ‘I didn’t want to sit out another election,’ she says, ‘as observer, analyst and scourge.’

McKew is one of Australia’s most experienced political commentators, but as a narrator she lacks a sense of irony and seems unaware of the ways in which the voyeur–player motif becomes twisted in her story. She also comes across as alarmingly naïve, a tendency which is fed by her dream run in 2007 election. ‘It felt as if someone had sprinkled fairy dust, such was the benign mood and sense of goodwill moving our way.’ And so the tale continues, until the crusader becomes the giant-slayer.

Any sense that McKew has become a player in the big league, though, is then rapidly dispelled as she finds herself relegated to a relatively minor supporting role in government, working through Julia Gillard’s office. It is not so much the subordinate position in policy formation that bothers McKew, but the experience of routine veto on public communications. ‘It’s not the message we want out there today.’ A speech she is to give at the Sydney Institute has to pass though three stages of vetting and approval before she is ‘allowed’ to deliver it.

Clearly, something is gravely amiss when a major political party not only fails to make an asset of one of the nation’s most skilled and high-profile public communicators, but also works to gag her at every turn. Here, though, is the irony. In the main game of power politics, the roles of the player who holds political office and the voyeur who belongs to the commentariat are radically intertwined, and in ways that do not necessarily give the upper hand to an elected member of parliament. If McKew wanted to be a player, she should have retained her position as presenter of Lateline, a role in which she had freedom of speech and could command respect from the leaders on both sides of politics.

After all, what is she doing in this book other than reclaiming the prerogatives of the reporter in a bid to set the record straight and settle a few scores? I am not wanting to suggest that there are machiavellian intentions here, but after her brutal immersion in realpolitik, McKew must surely be aware that writers and commentators, and, most especially, those who present as literary authors, are not just voyeurs. They can be lethal players.

In the unfolding drama she chronicles, this has been most graphically demonstrated by David Marr, whose Quarterly Essay ‘Power Trip’ appeared in the first week of June 2010, two weeks prior to the unseating of Kevin Rudd. There is no evident causal relationship, but unquestionably Marr’s venomous exercise in personality profiling had an influence on Canberra insiders already nervous about Rudd’s plummeting approval ratings.

McKew’s book might be a welcome counterbalance to Marr’s view of Rudd as ‘a weird guy and a failing prime minister’, but she has a character assassination of her own to pursue. In the chapter titled ‘Ambush’, which offers a forensic account of the circumstances leading to Rudd’s overthrow, Gillard is portrayed as a ruthless and scheming operator, formidable in her efficiency, with a career course set in fast forward for the top job. Her bid for the hearts and minds of the voting public in the 2010 election is summarised as ‘a low-rent, timid, inglorious campaign that shamed us all’.

As a public figure, McKew impresses with her poise and with a cool presence of mind that rarely falters, but it is quite evident from these pages that she is still reeling from the Rudd débâcle, her own loss of Bennelong in 2010, and, perhaps more than anything, from the damage to her political ideals. If she wanted to write a good book about her experiences during this extraordinary period of Australian political life, she should have waited. She should have taken more time over it.

What we have here is not so much a book as a publisher’s book product, compiled to an editor’s template and designed to cause a stir. As a writer and thinker, McKew could do so much better. I hope that one day she will.

Comments powered by CComment