- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

State governors hold a curious role across Australia, one that will be called into question when – one of these fine days, but none too soon – our nation becomes a republic. There will be lots of fine-tuning to be done before that, from the roles of Her Majesty’s representatives here all the way down to Royal Park, Royal Melbourne Golf Club, and the RACV. But this book is the biography of a state governor, one who was also an influential minister of religion, among other things. Above all, he was Master of Ormond College, at Melbourne University.

- Book 1 Title: Davis McCaughey

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Life

- Book 1 Biblio: UNSW Press, $59.99 hb, 400 pp, 9781742233611

Hilaire Belloc’s Lord Lundy was destined for a career in politics, but lacked the gumption and wept too much: nothing menial enough could be found for him, so his grandpa cried out in despair, ‘But as it is! … My language fails! / Go out and govern New South Wales!’ No doubt we have had plenty of such, over the decades, tottery generals and doddery aristocrats sent off to serve their time as governors in the colonies. But time moves on, with steady, staggering tread.

Victoria began with a governor of great flair in Charles Joseph La Trobe (1851–54), but none of his successors has served with more versatile distinction than Davis McCaughey (1986–92). His balance of ardour, intelligence, and charm stood out remarkably, and it is plain that in his maturity the Ulster Presbyterian minister had learned the ways of relaxation. We can, for instance, read him and his late wife, Jean, variously through their talented children.

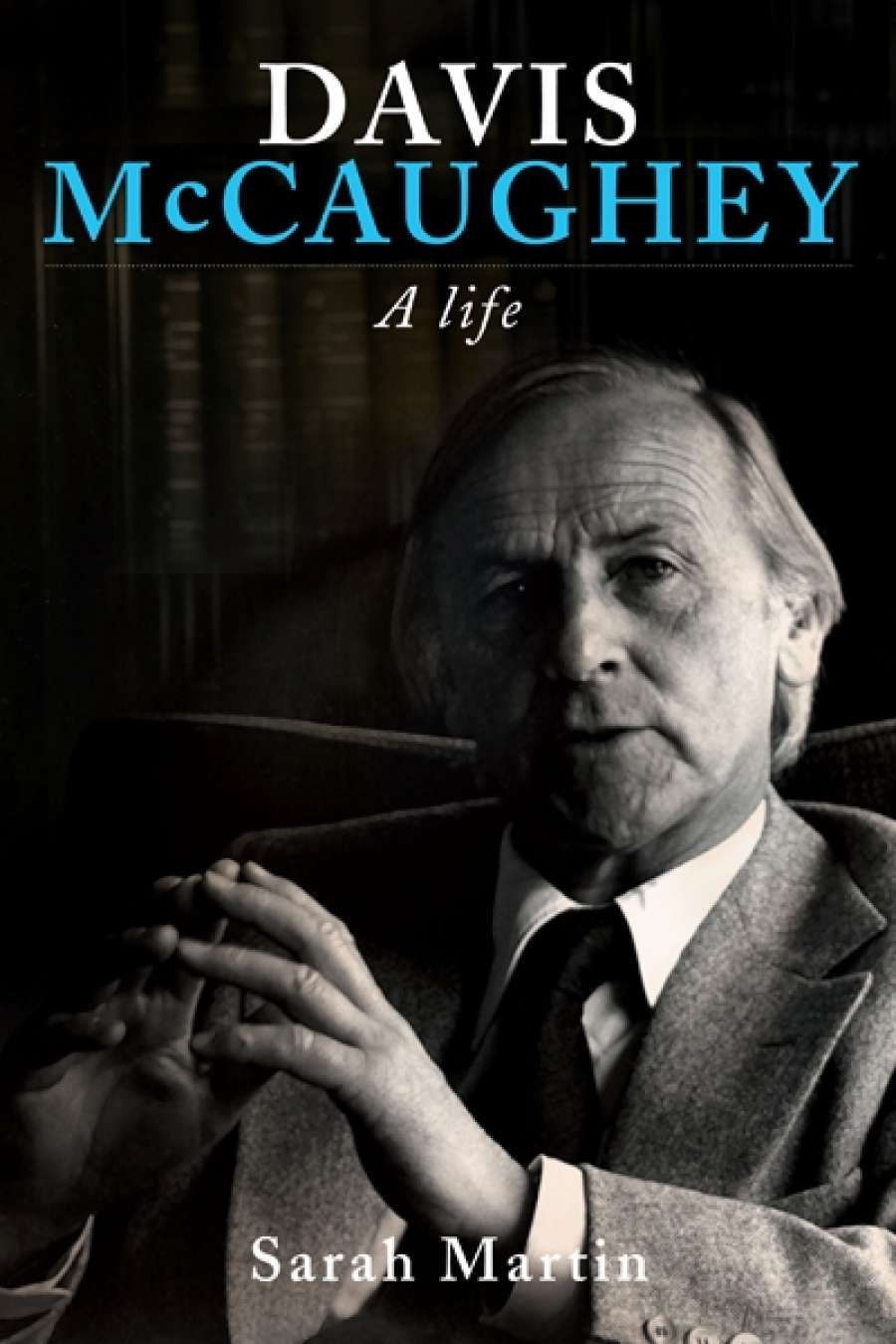

This new book is a ‘life’, with a dapper photograph of Davis on the front cover. The McCaugheys were sufficiently at ease in the world to look good in public without having to put on dog. Intelligence normally looks impressive. Interestingly, a portrait here of Davis’s grandfather looks strikingly like the James McCaughey of my generation. Genes are funny creatures; and cameras are something else.

Davis grew up in a settled family, enjoying Belfast bourgeois comfort, but with education and a strong backbone of Presbyterian faith: a familiar tradition in that passionately divided region of Ireland, where one man’s Derry is another chap’s Londonderry. His parents were conservative, not fissiparous, it seems, but we do not get an intimate feel of those early years in this book: Sarah Martin has a social historian’s telescope and touch. It could be said that she displays both the advantages and the limitations of this. She convincingly locates Davis’s development through the tides and eddies of mid-twentieth-century Protestantism, years that took in Karl Barth and Reinhold Niebuhr, but also the populist rise of Billy Graham. Yet often the book stands too far away from the man himself; the diction can be Latinate and judiciously abstract.

I think of passages like ‘Culture and behaviour could be interpreted and expressed in different ways, and tolerance and understanding were essential components of a healthy community’. Moreover, what specifically is meant by ‘the pluralist intellectual tradition where all knowledge was integrated’? I am not sure whether this is really a liberal humanist ideal or a kind of oxymoron. And one tiny point: Dinny O’Hearn should not appear as the feminine ‘Dinnie’: he wouldn’t have liked it at all.

Admittedly, Martin’s task is not an easy one, for this book exists also as an account of Presbyterian policy and practice after World War II: decades in which Christian belief had a diminishing hold. At the same time, ecumenical impulses were growing stronger. In practice the author is, as I have suggested, a socio-political writer about religious institutions, particularly the Student Christian Movement in Britain and sturdy Ormond College. Yet she also moves closer and writes that

there were ambiguities and contradictions in McCaughey’s character. To assume that he had always planned to go into the Church is to ignore the maverick element in his personality that was to become more obvious, a kind of daredevil approach to life.

Or that ‘His Irish lilt charmed those he met, as did the way his eyes lit up with interest and pleasure at chance encounters on the campus.’

The book follows Davis from his early SCM years into the ministry, to England for a while, and then way across the world to the Presbyterian Theological Hall, in the grounds of Ormond College, Parkville. When he, his wife, and five children had settled in, their impact was immediate. One former student said that meeting him ‘was like fresh air blowing in an open window’.

A spiritual chancer, but a Christian one. And tough, into the bargain. Davis fought hard in College and ecumenical battles, yet he always sought to reach out to others, treating them as fellow human beings. What is more, Jean was always there, solidly beside him, with her passion for social justice.

To revert to Davis’s Ormond years, it is quite hard these days to grasp how far those University colleges were badged with doctrinal difference, as was the broader community. My father would complain to me sometimes about ‘whining Micks’, regarding them as even worse than Masons. Meanwhile, back on campus, the Newman student ‘Black’ Jim Morrissey once appropriated Hobbes in the pages of Farrago, writing that the Ormond College XVIII was ‘nasty, brutish and short’. The colleges were unlike those comically celebrated by Evelyn Waugh and Anthony Powell, most of the time at least: yet there are some glimpses here of Ormond japes, amid the benign gravitas of Davis’s twenty-year rule.

Later on, his impact as governor of Victoria was to be similarly benign Indeed, in Martin’s words, ‘McCaughey saw his primary role as one of reaching as many people as possible’ and his years at bosky, Italianate Government House embraced poetry readings and all the signs of gracious informality: a certain diminution of the usual pomp. Once again, though, the author’s emphasis is on his socio-political role, particularly given the previous, conservative governor’s having been dismissed on grounds of perceived impropriety.

Davis McCaughey, having come to Melbourne from Ulster, like his persuasive successor on the campus, the late Graham Little, left a distinctive impress on our culture. Sarah Martin’s scholarly biography gives us his career, yet it might just as easily be taken as a study of ecumenism and the emergence of the Uniting Church in Australia. What is more, McCaughey governed Victoria in style for six years, which is not to be sneezed at. Incidentally, Fred Williams’s profile portrait of the man hints convincingly at the steel that went with the style.

Comments powered by CComment