- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: David McCooey reviews the new biography of Leonard Cohen by Sylvie Simmons

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

One day in 1984, Leonard Cohen played his latest album to Walter Yetnikoff, the head of the music division of Cohen’s record label, Columbia. Yetnikoff listened to the album, and then said, ‘Leonard, we know you’re great, we just don’t know if you are any good.’ Columbia subsequently decided against releasing the album, Various Positions (1985), in the United States, the lucrative market that Cohen had failed to crack since his début album, Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967). Columbia failed to foresee that Various Positions contained the song that would become Cohen’s most famous, ‘Hallelujah’, which Sylvie Simmons describes as an ‘all-purpose, ecumenical/secular hymn for the New Millennium’. It’s been covered by countless singers and X Factor contestants.

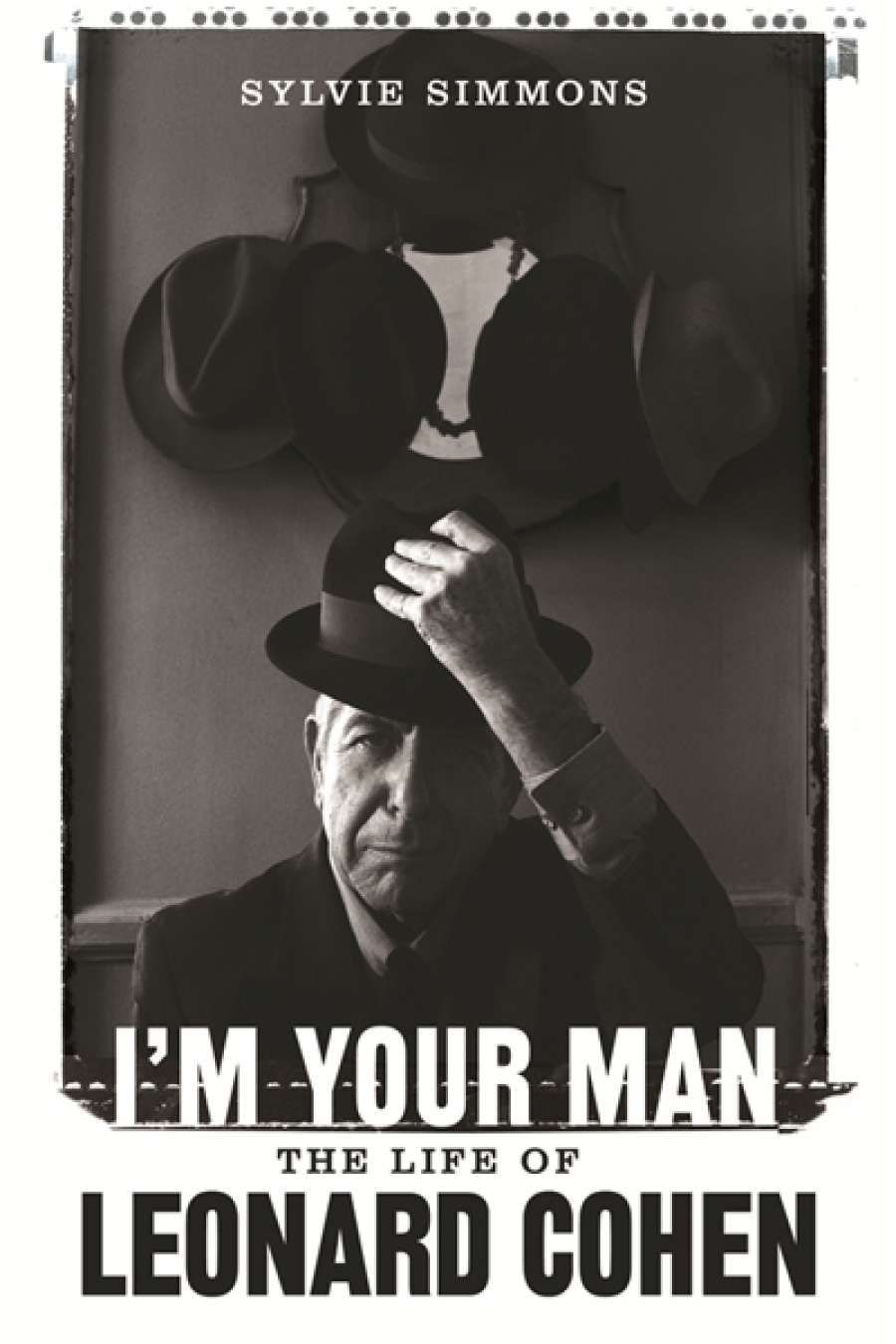

- Book 1 Title: I'm Your Man

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Life of Leonard Cohen

- Book 1 Biblio: Jonathan Cape, $35 pb, 564 pp

Yetnikoff’s ambivalence about Cohen’s talent may not have surprised Cohen; he himself never made large claims for his musical ability. In Michael Palmer’s film of Cohen’s 1972 European tour, Bird on a Wire (1974), Cohen admits to journalists that ‘I don’t have a good voice; everybody knows that’, adding that ‘the fact that my work is popular does not necessarily mean that it is good’.

What comes across more powerfully in Palmer’s film than in Simmons’s biography is Cohen’s enigmatic quality, a quality to which Yetnikoff’s comment surely adverts. For a figure so universally described (at least in the first part of his musical career) as ‘depressing’, Cohen is surprisingly mercurial. In Bird on a Wire he engages in funny self-mockery on stage, and is quickly moved from laughter to tears. In an earlier film, Ladies and Gentlemen ... Mr. Leonard Cohen (1965), Cohen is like a stand-up comic in his banter with his audience, not something one might expect from the master of ‘music to slit your wrists to’ (as he was known for a time in the 1970s).Cohen’s mysterious quality can also be seen in the way he regards the world of celebrity – journalists, adulatory crowds, young women making sexual advances – with a mixture of resignation, confusion, and amusement. (Cohen’s band on this tour dubbed him ‘Captain Mandrax’, in recognition of his drug du jour, so his use of the eponymous sedative no doubt had something to do with the ‘dazed’ part of his demeanour.)

If Simmons downplays Cohen’s enigmatic quality (though not his sense of humour), she does note two things central to the enigma of his career in popular music: its longevity and its unlikelihood. For a pop star in the 1960s, Cohen was improbable on a number of counts. He had an haut-bourgeois background (a well-connected Jewish business family in Montreal); he had wanted as a child to attend a military school; he had a Bachelor of Arts from McGill, and had begun a higher degree at Columbia (the university, not the record label).

Most of all, he was not young. When Songs of Leonard Cohen was released at Christmas 1967, Cohen was thirty-three years old, having spent the previous decade building a reputation as a poet and novelist. Whereas John Lennon and Bob Dylan flirted with being writers rather than ‘just’ songwriters, Leonard Cohen actually was one. He had been a prize-winning writer in Canada, someone on the fringes of the Beat movement in New York, and a member of the bohemian community on the Greek island of Hydra (which included the Australian expatriate writers George Johnston and Charmian Clift, with whom Cohen was friendly).

Unlikelihood is also a feature of many of the anecdotes in I’m Your Man, such as the story of Cohenvisiting Cuba just in time for the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, like a real-life Woody Allen in Bananas. This, like so many aspects of Cohen’s life, reads like fiction. When Cohen is told that his presence at the Canadian embassy is urgently requested, only to be told by the vice-consul there that ‘Your mother’s very worried about you,’ the writer of that fiction could have been Evelyn Waugh.

Other stories are unlikely (to the point of sounding apocryphal), because they so neatly prefigure major themes or events in Cohen’s life. An example of this is the story of Cohen’s youthful interest in hypnotism. Acquiring in his early teens a book called 25 Lessons in Hypnotism: How to Become an Expert Operator, Cohen has ‘instant success with animals’. Turning to human subjects, he hypnotises the family’s maid and tells her to undress. Unable to wake the undressed woman from her trance, the young Cohen begins to panic, fearing his mother’s imminent return. As Simmons notes, the mix of eroticism, impending doom, and loss is ‘exquisitely Leonard Cohenesque’. As Simmons also suggests, Cohen’s powers as a singer and performer have always been notably mesmeric.

What Simmons does not note is that poetry is itself a mesmeric power. Metrical speech, as some have posited, may have come into being as a form of hypnotism, a way to maintain ‘power’ over an audience. Cohen, whether in print, recording, poetry, or song, routinely relies on this power. ‘Suzanne’, his first well-known song, illustrates this: ‘Suzanne takes you down / to her place near the river / you can hear the boats go by / you can spend the night beside her / and you know that she’s half crazy / but that’s why you want to be there.’ The use of accentual metre here, rather than the more traditional accentual-syllabic, produces a hypnotic tension between the recurring three stresses per line within unpredictable line lengths.

There are plenty of biographies of Cohen on the market. Ira B. Nadel’s Various Positions: A Life of Leonard Cohen (1996) remains the most literary in approach.Simmons’s biography updates the story, covering Cohen’s period as a Buddhist monk (another enigmatic move) and his late-career flowering as a septuagenarian performer, undertaking a massive world tour after discovering that his manager had misappropriated his riches. Given that it seems obligatory for trade biographies to be the size of a brick, Simmons’s biography is more detailed than Nadel’s, especially with regard to Cohen’s early life (though most of the Q&A sections between Simmons and her subject could easily have been cut).

Simmons is at her weakest when attempting to be literary, and at her best when most journalistic. She gives compelling accounts of, for instance, Cohen’s appearance at the 1970 Isle of Wight festival, the recording of his albums (with 1977’s Phil Spector-produced Death of a Ladies’ Man, not surprisingly, offering plenty of anecdotes), and Cohen’s long romantic history.

For someone like me, born the year Songs of Leonard Cohen was released, Cohen has been a lifelong presence. It may be impossible to decide whether he is good rather than simply ‘great’, but certain moments in Cohen’s long and unlikely career, such as ‘Stranger Song’, ‘You Know Who I Am’, ‘Dress Rehearsal Rag’, ‘Joan of Arc’, and ‘Chelsea Hotel #2’, have an extraordinary staying power. Cohen, whose last album, Old Ideas (2012), made him the oldest chart-topper in Finland at the age of seventy-seven, seems to just keep going. Simmons quotes him as saying that he ‘has no sense of or appetite for retirement’. It is hard to imagine him dying. It would be more appropriate for an unseen hand simply to pull down the master fader mid-phrase, just as it does at the end of the title track of I’m Your Man (1988). If so, the hypnotic spell might finally be broken.

Comments powered by CComment