- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cricket

- Custom Article Title: Brian Matthews reviews 'On Warne'

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In his The Art of Wrist-Spin Bowling (1995), Peter Philpott remarks: ‘If there is one factor in spin bowling which all spinners should accept … it is the concept that the ball should be spun hard. Not rolled, not gently turned, but flicked, ripped, fizzed.’ Richie Benaud agrees: ‘Spin it fiercely. Spin it hard.’ The intensity of the grip that produces ‘fizz’ will also often result in the ball either floating high and free in the air or thumping into the pitch a few yards ahead of the popping crease.

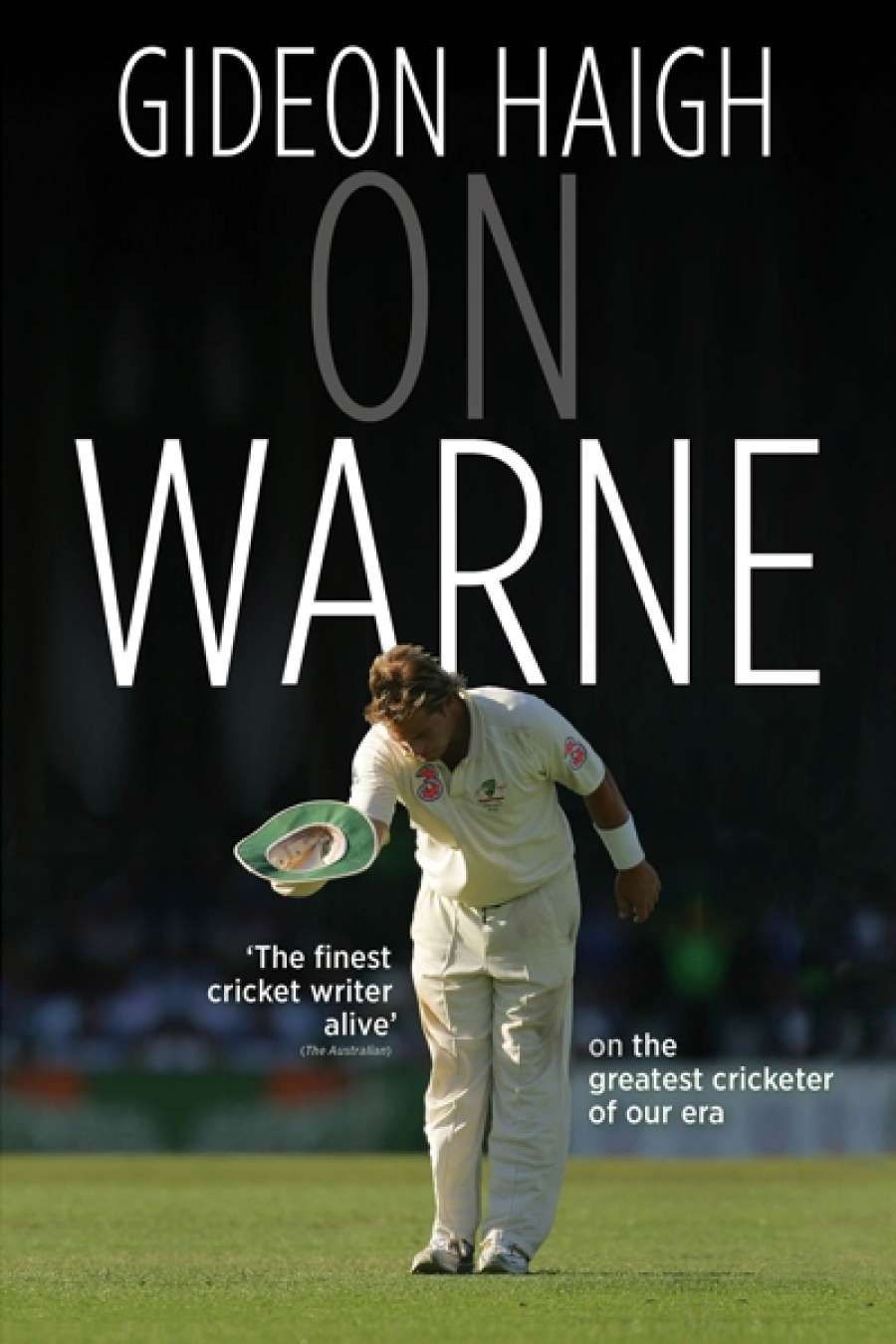

- Book 1 Title: On Warne

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $35 hb, 211 pp

Shane Warne, as Gideon Haigh points out, gave it a rip: ‘Leaving his hand, the ball emitted an audible flit-flit-flit-flit, then, on descending to earth, deviated as much as half a pitch’s width.’ It was the descent to earth that was the problem. In his early leg-spinning days, as Warne recalled, like the rest of us he ‘could never land the bloody thing’. But he didn’t stay like the rest of us for long.

Haigh’s utterly addictive book traces how and why Warne became different, sui generis, and is framed as an anatomy of the phenomenon – ‘The Making of Warne’, ‘The Art of …’, ‘The Trials of …’, ‘The Sport of Warne’ – reminiscent in its methodology of the classic essay mode: Hazlitt’s ‘On Poetry’ and ‘On Prejudice’, for example, or Montaigne’s ‘Of Constancy’ and ‘Of Fear’. This format and the references it suggests are important because it is a method that allows, above all, for a sense of calm, an experience of measured, point-by-point consideration, a refusal either to be rushed to judgement or easily impressed by received wisdom. And if ever there were a subject that cried out for this kind of general literary decorum and reasoning it is Shane Warne.

Haigh does not duck the challenge of dealing with Warne’s sometimes spectacular off-field adventures. They are all there – the texting, the Saleem Malik affair, the banned diuretic, and the rest – and sensibly considered, as are Warne’s own, scarcely heard objections on those rare occasions when he had any reasonable defence: ‘Explicit talk on the telephone did not mean all of a sudden I’d lost my flipper or forgotten how to set a field.’ But Haigh is rightly much more interested in, and before anything else attentive to, the cricketer and his genius. ‘I have some expertise about Warne the cricketer,’ he explains, ‘… but not much about Warne the person … And … that suits me fine. I only wished to watch him play cricket; I didn’t want to marry him.’

The section on the art of Warne includes a masterly evocation of the Warne leg break. The brief approach, ‘eight paces, that’s all it was’; the mannerisms: ‘an unconscious but unvarying rubbing of the right hand in the disturbed dirt of the popping crease’; ‘the easy relaxed saunter’ to his bowling mark, ‘whether he’d just beaten the outside edge or been hit for six’; the pause, ‘the best pause cricket has known, pregnant, predatory’. Anyone who has sat in the sun at the MCG or under the Moreton Bay Figs at Adelaide Oval or at any other of his famous hunting grounds here and overseas watching Warne will feel the hair on the back of the neck rise reading this description, because it is exactly right; it is the action portrait of the greatest spin bowler any of us will ever see.

The section on the art of Warne includes a masterly evocation of the Warne leg break. The brief approach, ‘eight paces, that’s all it was’; the mannerisms: ‘an unconscious but unvarying rubbing of the right hand in the disturbed dirt of the popping crease’; ‘the easy relaxed saunter’ to his bowling mark, ‘whether he’d just beaten the outside edge or been hit for six’; the pause, ‘the best pause cricket has known, pregnant, predatory’. Anyone who has sat in the sun at the MCG or under the Moreton Bay Figs at Adelaide Oval or at any other of his famous hunting grounds here and overseas watching Warne will feel the hair on the back of the neck rise reading this description, because it is exactly right; it is the action portrait of the greatest spin bowler any of us will ever see.

Like a composer reprising a great theme, Haigh returns pages later to ‘the pause’, to examine its psychology.

He presented his opponent with a narrative. I am better than you, he said; everybody knows this, but circumstances decree that we should go through the motions of proving the obvious. I am better than you … therefore I dictate the terms of our engagement, bowling my overs at my own pace … There stood Warne at the end of his mark, curling the ball from hand to hand … Through his unhurried survey of the scene, he could keep the batsman in his crouch that little longer than perhaps was comfortable … That pause: it was almost imperceptible, yet time would seem to stand still.

Haigh here detects and examines Warne’s ‘narrative’ and then inhabits it. The result, to which a précis scarcely does justice, is a marvellous analysis of the Warne mystique and the prodigious talent feeding it. This is cricket writing as art, turning the creative leaps familiar in fiction or literary non-fiction to the task of anatomising the ungraspable nature of genius.

Haigh’s own narrative is fluent, confident, and notable for an unselfconsciously adduced broad range of reference. Cavaliers and Roundheads, Donald Rumsfeld, Philip Roth, Ernst Blofeld and his cat, Rashomon, William Faulkner, Mandy Rice-Davies, and The Good Soldier are just some of those that emerge, each with its own ironic, witty, or enlightening enrichment of the story. You keep up if you can.

On Warne is a sublime treat. It concludes with a reference to Hazlitt’s description of John Cavanagh, the fives (handball) champion of his day. ‘In describing Cavanagh,’ Haigh explains, ‘the essayist invited his readers to consider not so much fives, or even sport, but mastery. “He could do what he pleased, and he always knew exactly what to do,” wrote Hazlitt. “He saw the whole game, and played it.”’

‘Just like Warnie,’ Haigh says.

Just like Haigh, we might add.

Comments powered by CComment