- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cricket

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At last, new Bradman territory to be conquered: the Don 1939–45 or, if we discount the ‘phoney war’ (‘Business as Usual’, as Robert Menzies said of that first phase in World War II), perhaps 1941–45. I imagined a slim volume. Not so! Instead, there is a catch to the subtitle of Bradman’s War: How the 1948 Invincibles Turned the Cricket Pitch into a Battlefield, which indicates that we will be on more familiar terrain.‘More familiar’ because this book is an attempt at revisionist history. Questioning the Bradman idolatry and the invincibility of the Invincibles is a suitable aim. However, the main task for the revisionist historian is to provide either fresh new evidence or a powerful reinterpretation of existing evidence as part of formulating a balanced argument: Malcolm Knox does neither.

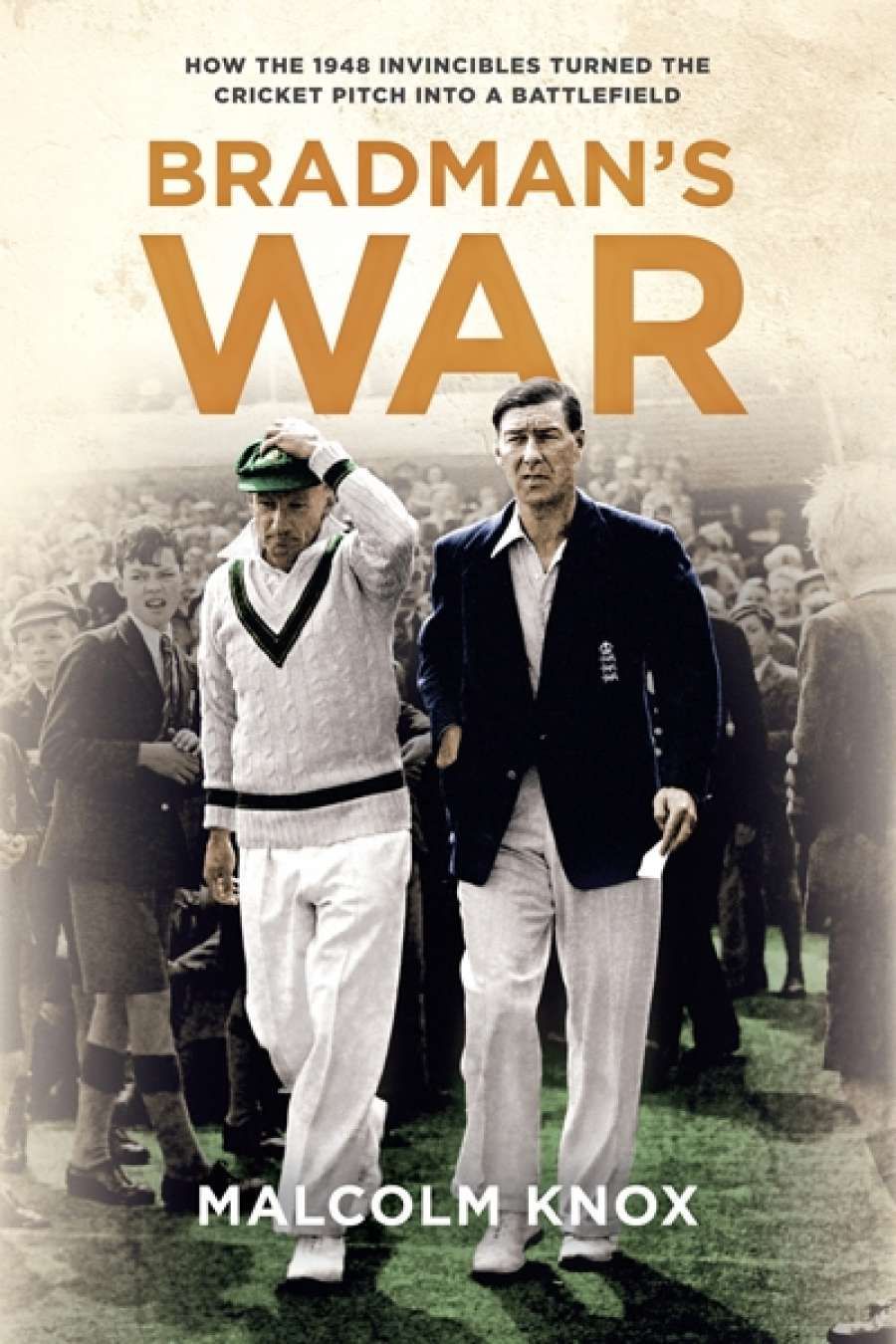

- Book 1 Title: Bradman’s War

- Book 1 Subtitle: How the 1948 Invincibles Turned the Cricket Pitch into a Battlefield

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $39.99 hb, 447 pp,

Knox’s central thesis is that, at the end of World War II, many test cricketers (Australian and English) wanted to play in the cavalier spirit of the 1945 Victory Tests rather than the brutal game of the 1930s, but that Bradman single-handedly killed that spirit. It is a weak thesis. Certainly, it is not difficult to understand the joy with which the servicemen of both countries (led by Wally Hammond and Lindsay Hassett) embraced the game at the end of the war, but to imagine that a new pattern of play would be established in Ashes matches is fanciful. The history of Anglo-Australian test cricket had been based on fierce competition; English professionals (particularly from the north) played hard – witness Yorkshire versus Lancashire encounters – as did professional turned amateur Hammond; and the same could be said of Australian cricketers and matches between New South Wales and Victoria.

Bradman’s War is a big book, nearly 400 pages of text and four centimetres across the spine. Knox spends 100 pages discussing the service backgrounds of Australian players (contrasting these with Bradman’s war), the Ashes series of 1946–47, the first Indian tour of Australia in 1947–48, and the voyage to England; two-thirds of the book is then devoted to the tour; and a final thirty-two pages to the tour’s legacy. I have no complaint with the structure.

The content is a different matter. While interesting points are raised regarding Keith Miller’s self-mythologising (particularly about his duck against Essex); Sid Barnes’s intimidatory presence at short leg; the use of leg theory as a defensive measure; the absurd distinction between gentlemen and players; the consuming of a ‘cold hamper meal and soft drinks’ on the train to Derby after the brilliant win at Headingley to seal the Ashes; and no discussion of Bradman having to make four runs in his final test innings to achieve an average 100, to mention a few – the most striking impression is of a long-winded hatchet job on the chief protagonist.

Knox prosecutes, Bradman is the defendant in the dock, and the roll-call of witnesses is long. According to the argument, Bradman has a soft war (following a brief role as a supervisor of physical training in the army and several bouts of fibrositis), unlike several of his fellow players:

By the time the Allied forces evacuated Dunkirk, when Bill Edrich was suffering the double-vision of death in the morning, and village cricket in the afternoon, when Lindsay Hassett was sitting on unexploded mines and Keith Miller was contemplating taking to the air, Don Bradman’s war was already over. In June 1941, he was formally discharged.

Bradman apparently also carries grudges against England: from his first test at Brisbane in 1928, from Bodyline, and from the Oval in 1938, when his side was defeated by an innings and 579 runs. He turns cricket into war to destroy his opponents.

A peculiarity of the book relates to its sources and how they are deployed. Knox relies almost exclusively on secondary literature – player autobiographies and tour accounts – except for recent interviews with Arthur Morris, Neil Harvey, Sam Loxton, and Englishman John Dewes. Why didn’t he use contemporary press accounts of the tour? Furthermore, what I cannot understand is why a writer with so many literary runs on the board – four novels, ten non-fiction works (including four previous cricket books), as well as being a Walkley Award-winning journalist – would take the role of substitute by relentlessly quoting other people’s work.

Loxton, Harvey, and Ian Johnson may be Bradman’s defenders among the witnesses Knox calls (a few players sit on the fence), but his prime antagonists are, unsurprisingly, his old foes Bill O’Reilly and Jack Fingleton, Keith Miller, Dick Whitington (subsequently Miller’s frequent co-author), and Miller’s English mate Denis Compton. After reading Bradman’s War, I did something that I have never done before for the purpose of a review. I conducted a content analysis of every tenth page of the book and counted how many lines were quoted. From thirty-eight pages and 1184 lines, 584 (or 49.3 per cent) were direct quotes. What is the author’s voice for if not to use?

In his final chapter, ‘The Legacy’, it might be expected that Knox would adopt judicial tones and draw his own conclusions. He does and he doesn’t. He makes a fair judgement comparing the 1948 team to earlier great Australian sides of 1902 and 1921, but saves the nastiest barb for Bradman, spending the war ‘on his wife’s parents’ farm at Bowral, and stockbroking for a crook in Adelaide’.

Knox is a one-eyed barracker, if not a hanging judge. His book leaves a sour aftertaste.

Comments powered by CComment