- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

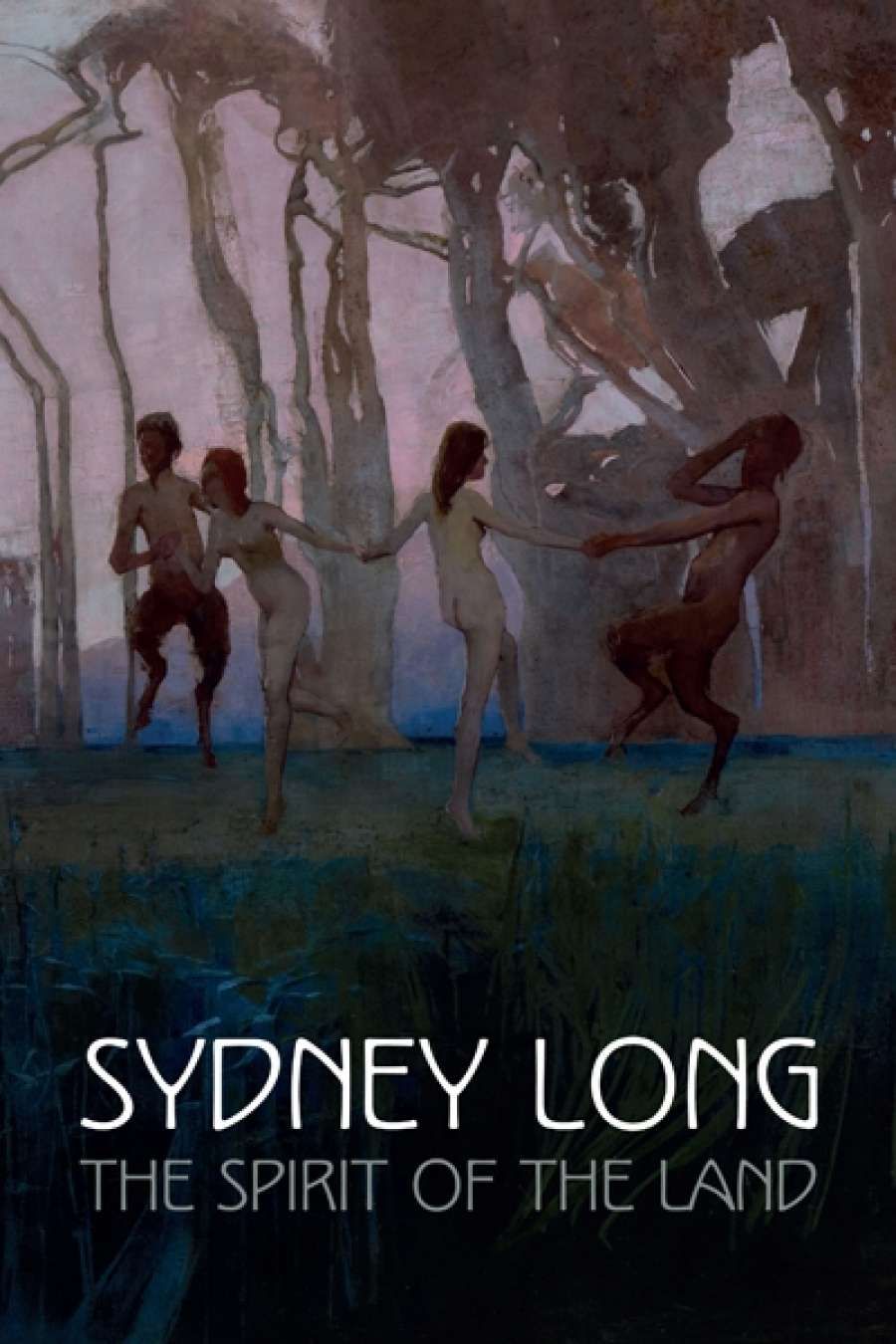

Symbolist art has received an unusual amount of attention recently. First there was Denise Mimmocchi’s Australian Symbolism: The Art of Dreams at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (which Jane Clark reviewed in the September 2012 issue of ABR). Now Sydney Long: The Spirit of the Land celebrates Australia’s foremost exponent of the movement. Sydney Long (1871–1955) was born in Goulburn, so the National Gallery in Canberra can claim him as a local talent. More importantly, they have staff with relevant expertise to mount this major retrospective. Anne Gray, the exhibition’s curator, is an authority on Edwardian Australian art. Ron Radford, the NGA director, was one of the first to look seriously at Art Nouveau in Australia; he curated a landmark exhibition on the subject as far back as 1981.

- Book 1 Title: Sydney Long

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Spirit of the Land

- Book 1 Biblio: National Gallery of Australia, $49.95 pb, 208 pp, 9780642334299

It is difficult to review a catalogue independently of the exhibition it documents. In the past, catalogues were primarily souvenirs. Today they are surrogates for the experience of viewing a show, as well as an important forum for critical writing. Sydney Long: The Spirit of the Land, shown at the National Gallery between August and November of 2012, made a memorable exhibition. All of Long’s major and well-loved paintings were there, displayed sensitively, with lesser-known works from private collections and an unexpected selection of watercolours and prints. The catalogue is a fine memento of the show, well produced, with colour reproductions that are faithful to the original works of art. Its quarto size allows for large reproductions and leaves sufficient space around the text for the inclusion of documentary imagery. Recently there has been a spate of much smaller exhibition catalogues, which look smart and sit nicely in the hand, but do not serve the imagery as well.

As a publication that aims at a longer shelf life, challenging and redefining our understanding of Long’s art, the catalogue is more synthetic than original, bringing together a wide range of recent scholarship in the field. Divided into four sections, the extended biography and critical essay on Long’s art are both the work of Gray. Roger Butler, senior curator of Australian prints and drawings at the National Gallery, contributes an essay on Long as a printmaker. The final section reproduces the 114 works from the show, with three hundred to six hundred words of text on each one. Gray has written the bulk of these, with other art historians contributing about a third.

Radford describes the introductory biography as ‘all-embracing’. To be fair to Joanna Mendelssohn, who wrote the first scholarly study of Long in 1979, online genealogical resources and digitised newspapers have made the biographer’s task much easier. Yet even with these resources, many aspects of Long’s life remain enigmatic. We cannot be sure, for example, when he was born or who his parents were. With such uncertainties, the biography often becomes conjectural (‘no doubt’, ‘he is likely’, ‘we can imagine’). Gray accepts the widely held view that Long was homosexual. This is based on artist Roy de Maistre’s disclosure that the two had an affair. Even if this is accepted, surely it is presumptive to advance such speculations about Long’s relationship with his wife as ‘it is possible Catherine did not need carnal love, taking refuge in household chores and assisting with Sid’s art’.

Gray suggests that Baron von Gloeden’s photographs of naked Sicilian boys, which began to be published in such popular magazines as The Studio from the early 1890s, might have inspired Long’s 1894 masterpiece By tranquil waters. Painted when Long was still a student, and showing a group of boys frolicking at the Cook’s River, it was purchased by the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Long’s first work to enter a public collection. Gray is on much firmer footing as she traces the artist’s development from the skilful but still conventional Impressionism of By tranquil waters to his proto-modernist works painted a number of years later. The Spirit of the Plains (1897) and Pan (1898) show Long’s characteristic decorative approach, harnessing the simplified and sinewy forms of Art Nouveau. Gray draws attention to an article that Long wrote in 1905 on ‘The trend of Australian art’. It reveals an artist who thought deeply about how the Australian landscape should be represented, as well as about technical questions of colour, composition, and iconography.

Long consciously attempted to create an alternate ‘Australian brand’ – as he himself described it – to the one of drovers and bushmen in expansive, sun-drenched landscapes. He did this through his subjects and palette, be-lieving that ‘if the delicate relation of colour values is not there, all the swagmen and crows in Australia will not make it Australian’. He thought that the more sombre side of the Australian landscape had been neglected; many of his images were set at twilight and dawn, painted in subdued greys, blue-greens, and purples. His aim was ‘to express the lonely and primitive feeling of this country. A feeling more suggestive of some melancholy pastoral to be rendered in music and perhaps beyond the limit of painting.’

Australian composers of the time, however, were not, unlike Long, up to the challenge. Debussy’s symphonic poem L’après-midi d’un faune, based on a Symbolist poem by Stéphane Mallarmé, was composed four years before Long’s Pan, but did not receive its first performance in Australia until the 1930s, typical of the much slower way innovations in music were transmitted. Gray admirably traces the complex web of stylistic sources that fed Long’s art, from Art Nouveau, made popular through publications, architecture, and the applied arts, to Symbolist subjects taken up by both painters and poets, along with older influences from Impressionism, French Realism, and Pre-Raphaelitism. Like the figure of Pan, who, Long said, was a hybrid, painted from an Irish model for the torso and a Sydney goat from the waist down, he skilfully fused all these sources to create some of the most compelling images in Australian art from the turn of the twentieth century.

A criticism made of Long, as indeed of many artists, is that he was inconsistent and that his works lost their vitality of expression after he moved to England in 1910. Gray manages to present a more multifaceted view of the artist than has been prevalent to date. Long himself was both modest and realistic about what an artist could achieve, writing that no one painter ‘can hope to play all the keys. His love for one particular theme in Nature’s rhapsodies will eventually colour all his work. And he is a clever man who prevents it becoming a mannerism.’

Comments powered by CComment