- Free Article: Yes

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Having attempted to connect with the art of painting by submitting to instruction on how to represent ‘apples and bananas and pumpkins and plaster casts’, Danila Vassilieff realised ‘it was all a waste of time, it was meaningless to me … That was dead life and I wanted to paint living life, life and nature and people in action and movement.’

- Book 1 Title: Vassilieff and His Art

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan Art Books, $69.95 pb, 231 pp, 9781921394874

- Non-review Thumbnail:

Born in 1897 in Don Cossack country, caught up in World War I, and then fighting with the White Russians against the Bolsheviks, Vassilieff first made it to Australia in 1923. After working at a variety of jobs as well as doing some painting, in 1929 he headed for South America, the Caribbean, and just about everywhere else. He exhibited some work in London around 1934 and returned to Sydney in 1936, when, as Felicity St John Moore explains, Australian art was crying out for someone as passionate and socially disconnected as Vassilieff.

By 1936 the Australian art collectors’ landscape-art obsession had not developed much beyond those deft Heidelberg School representations of grazing country with blue hills at the back. There were occasional, various, and cautious adaptations of post-Cézanne and Cubist stylisations brought to Antipodean shores by arty travellers. In general, however, the expressionist notion that an artist should just go for it, with the brush directed by the mind more than by the eye, was considered degenerate. In 1937 Robert Menzies and a bunch of gentleman’s club-style painters formed the Australian Academy of Art to preserve us from moral collapse following exposure to wild brush strokes, random distortions, abrupt tonal changes, and disharmonious colour. At that time, Hitler was saving Germany from the same perceived danger of cultural disintegration.

The first five chapters of this book appeared in 1982 under the same title, published by Oxford University Press. Now, coinciding with the recent exhibition Danila Vassilieff: A New Art History at Melbourne’s Heide Museum of Modern Art, it is presented in a larger format, with more and superior reproductions of paintings and sculptures, as well as wonderful photographs of the artist ‘living life’ to the full. There are five additional chapters dealing with Vassilieff and folk images; sculptures celebrating Stenka Razin, a seventeenth-century Cossack peasant rebel; Angry Penguins and 1940s realist painting; icons and politics; the Ballets Russes; and Vassilieff’s influence on Nolan.

It is interesting to note that recent auction records show an average price for a Vassilieff of $2767, while the figure for an Arthur Boyd is $134,220. This is despite the fact – as St John Moore so powerfully argues – that Arthur Boyd, Sidney Nolan, John Perceval, and others were inspired by Vassilieff’s approach and by the paintings he produced in celebration of ‘living life’ rather than refining a personal style (brand?) for the market.

In ‘From Vassilieff to Nolan: The Secret of the Kelly Series’, the last of the new chapters, St John Moore comments that ‘Nolan admitted to being influenced by Vassilieff (the most spontaneous person he had ever met), arguing that it was the simplicity of what he said – the message not the aesthetic – that made him so effective. New evidence shows that Nolan also made a secret study of Vassilieff’s painterly visual language, extracting from it his method of burying layers of personal and cultural meaning into his iconic Kelly series.’

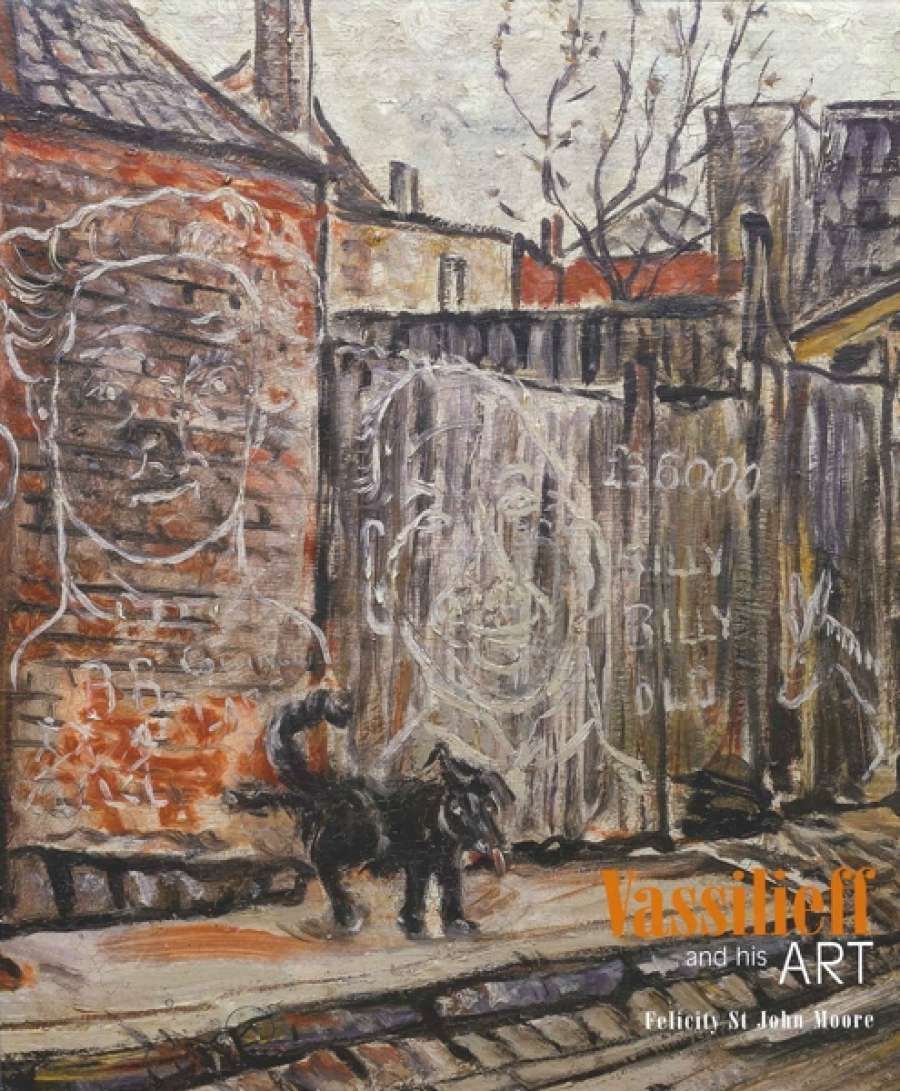

The rapid evolution of this footloose Cossack’s painting in Australia is almost as striking as the works themselves. Street in Surry Hills (1937),whichincludes a self-portrait, is a free and partially dry-brushed image that might well have been a stylistic signal for the social realists who emerged around 1938. St John Moore observes of paintings of this period that ‘[Vassilieff’s] austere palette, arguably the product of necessity, reflected both his own mood and the prevailing state of depression’. Regarding the late 1930s Sydney paintings, the leftist artist Noel Counihan is cited as one of those who ‘came to realise, however, that the work was not polemical; it derived from human sympathy, from Vassilieff’s identification with the people of the slums, and to some extent therefore, from the similarity between raw existence in Woolloomooloo and life in a Cossack village.’

Of course, Vassilieff didn’t sell back then. It was the Depression, and the affluent few didn’t favour his works. Street Scene with Graffiti (1938),the painting reproduced on the cover, presents viewers with a freely brushed affirmation of Melbourne’s urban poverty: there is a dog lifting its leg, a horse and cart creaking along a back lane, faces and writing scrawled on rear-lane fences, and backyard dunny walls.

In 1939 Vassilieff moved beyond Melbourne’s urban fringe to Warrandyte, as the foundation art teacher at Koornong Experimental School. As well as teaching he worked on the school’s buildings and went on to construct ‘Stonygrad’, an extraordinary house now on the Heritage register. In Warrandyte he also extended his visual imagination by working on stone figures that were stylistically modernist while connecting back to the very beginnings of art.

Three years before his death in 1958, Vassilieff was teaching at a government school in Mildura where, beyond the reach of Melbourne’s art world, his by now highly coloured paintings pushed the boundaries of modernist expressionism even further.

Art monographs often disappoint, but not this one. For readers with little interest in or contact with the art world, Vassilieff and His Art remains a valuable piece of social history presenting a larger-than-life central character of the kind many market-conscious novelists hunt after in their dreams. What’s more, the writing is focused: St John Moore eschews the waffle which so often clogs that space between image and language.

Comments powered by CComment