- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Natural History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Curious Minds sets out to explore the naturalists and scientists who brought Australia’s flora and fauna into the public consciousness: on the face of it a laudable aim, but one not totally fulfilled. From the title onwards the book seems confused in its aims and in its style. Is the book intended to be about people (the curious naturalists), flora and fauna (their discoveries), or both? Does it aim to provide new insights about the twenty-six selected naturalists and the culture within which they worked, or is the intent to provide a popular, even slightly scurrilous, account of the lives of selected individuals?

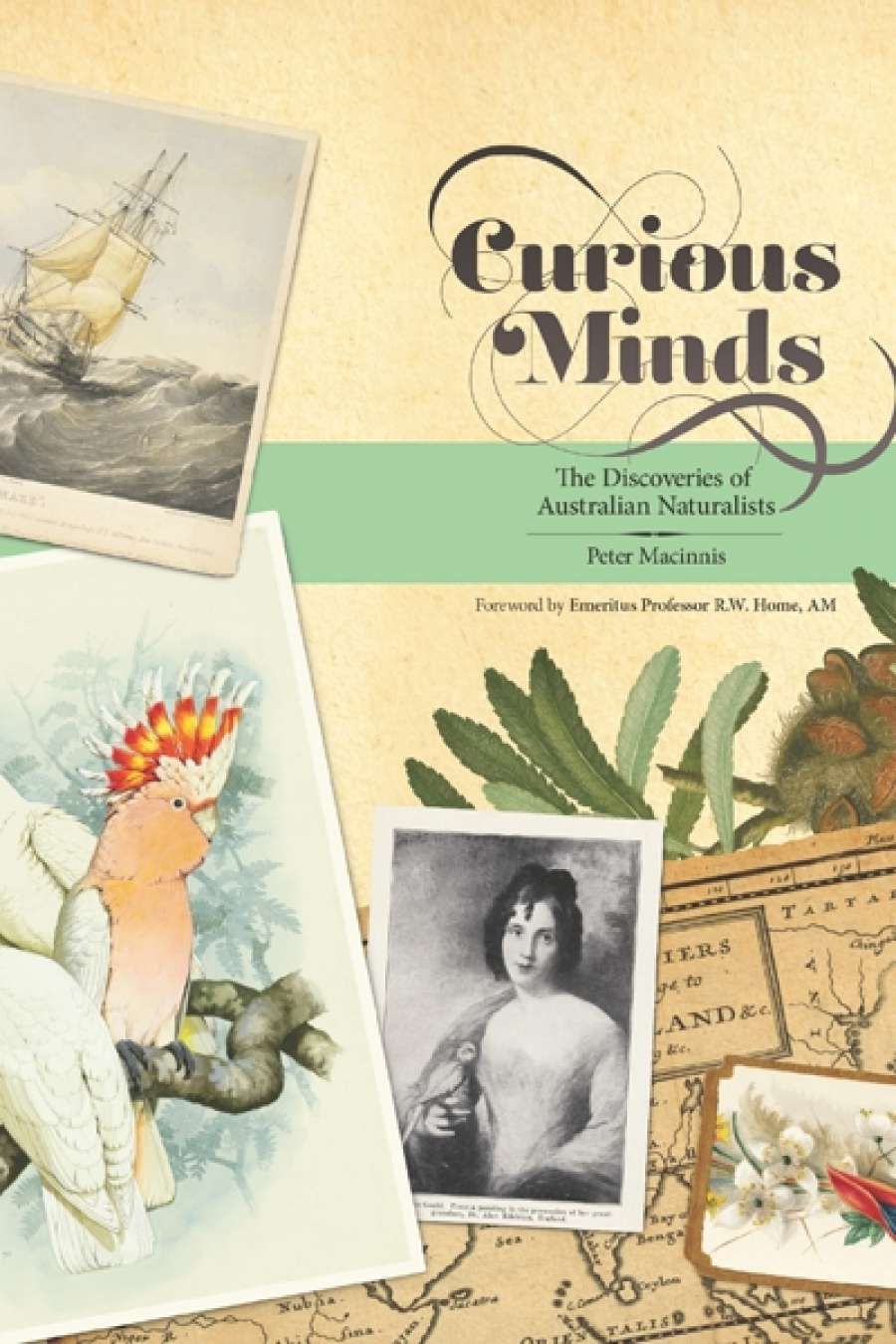

- Book 1 Title: Curious Minds: The Discoveries of Australian Naturalists

- Book 1 Biblio: National Library of Australia, $39.99 pb, 213 pp, 9780642277541

The book is copiously and beautifully illustrated with historical paintings, portraits, maps, and diagrams from the collections of the National Library of Australia. These are usually pertinent to the story, but sometimes the links seem tenuous, or the illustrations are not placed in context. In previous NLA titles that showcase the institution’s image library, the images have been the clear focus – for example, Penny Olsen’s Upside Down World: Early European Impressions of Australia’s Curious Animals (2010). Curious Minds, however, concentrates on the people, in which case one would expect the illustrations to be carefully chosen to supplement the text, rather than dominate it. I couldn’t help wondering whether the aim of publishing illustrations had a disproportionate influence, reducing the space available for words. It seemed that the illustrative icing overwhelmed the cake.

The book is divided into six chapters designed to cover stages in the evolution of European understanding of nature in Australia. Each chapter comprises between three and six accounts of an individual or team of scientists or artists and their work. These range in length from less than two pages of text (covering La Billardière and Riche, naturalists with D’Entrecasteaux’s expedition) to six pages (William Caldwell, a scientist from Cambridge, who finally solved the riddle of whether or not the platypus laid eggs).

The first chapter deals with the earliest explorers and how they interpreted Australian nature from a European perspective. The second looks at the more intensive explorations that specifically included naturalists/scientists. The third examines scientists who lived in Australia or visited for extended periods, allowing substantial, focused research to be undertaken. The fourth looks at naturalists who came to grief in various ways and for varied reasons. In the fifth chapter, home-grown naturalists (including pioneering women) who made long-term contributions are celebrated. The last chapter gives credit to natural history artists and entrepreneurs, notably John Gould, who, as Macinnis points out, was the equivalent of David Attenborough in his celebrity and impact, if not in his business ethics. These personal accounts make interesting reading, as would be expected for any group of high achievers (naturalists are only human, after all), but my overall impression is that they are too brief and tabloid in style, and ultimately left me wanting more detail and a less sensationalist approach. Digressions about the private lives of some of the subjects come at the cost of greater discussion of the significance of their work. The chapters are bound by artificial and arbitrary divisions that overlap extensively in time, and individual accounts are not necessarily chronological. I found myself wondering which years I was reading about, and how the work of the various naturalists fitted together in the history of Australian natural science.

A book’s bibliography provides a ready insight into the quality of research underlying the text, so I always head there early in any review. Even here I am perplexed. The endnotes for each chapter are extensive and indicate a detailed use of the NLA’s wonderful Trove database. This has revealed, for this reviewer at least, numerous newspaper articles on natural science, explorers, and scientists, important resources that I am keen to explore further. However, a number of standard published works are missing: for example, the reviews of Finney (1993) and Moyal (1976, 1986) on colonial science in Australia. Numerous works on individual naturalists seem not to be listed: for example, George (1999) on Dampier, McMinn (1970) on Alan Cunningham, Marshal (1970) and the Nicholsons (2002) on Darwin and Huxley. In the case of Ludwig Leichhardt, the highly critical and somewhat discredited views of Chisholm (1955) dominate over more recent and carefully considered accounts, such as that of Webster (1980). This is just a small selection of sources that came readily to mind; there are numerous others that should have been consulted. My concern was partly allayed when I found an obscure editor’s note at the foot of the imprint page, giving a web address for a ‘full list of references’. However, the titles mentioned above are not to be found there either. The impression remains that the author has been rather selective in his research, while bringing to light some previously less accessible material via Trove.

In the first paragraph I questioned the purpose of this book. I am still unsure of the answer. A fascinating set of characters was chosen for inclusion, but the biographies are too brief, chatty, and disjointed to be satisfying, and there is disappointingly little information about the subjects’ discoveries. It is, however, a handsome production that showcases many beautiful historical works of art, and is exceptional value for money.

Comments powered by CComment