- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Two biographies of Gina Rinehart

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Reading two books about Gina Rinehart back to back is far from edifying. So rich, so controlling, so opinionated, so entitled – and these are among her less objectionable qualities, as described in the two biographies published since she burst into the headlines amid reports of family litigation, media buy-ins, and escalating wealth. Indeed, whatever she did would captivate widespread interest, given that her worth ballooned from a tidy $900 million in 2006 to $20 billion this year.

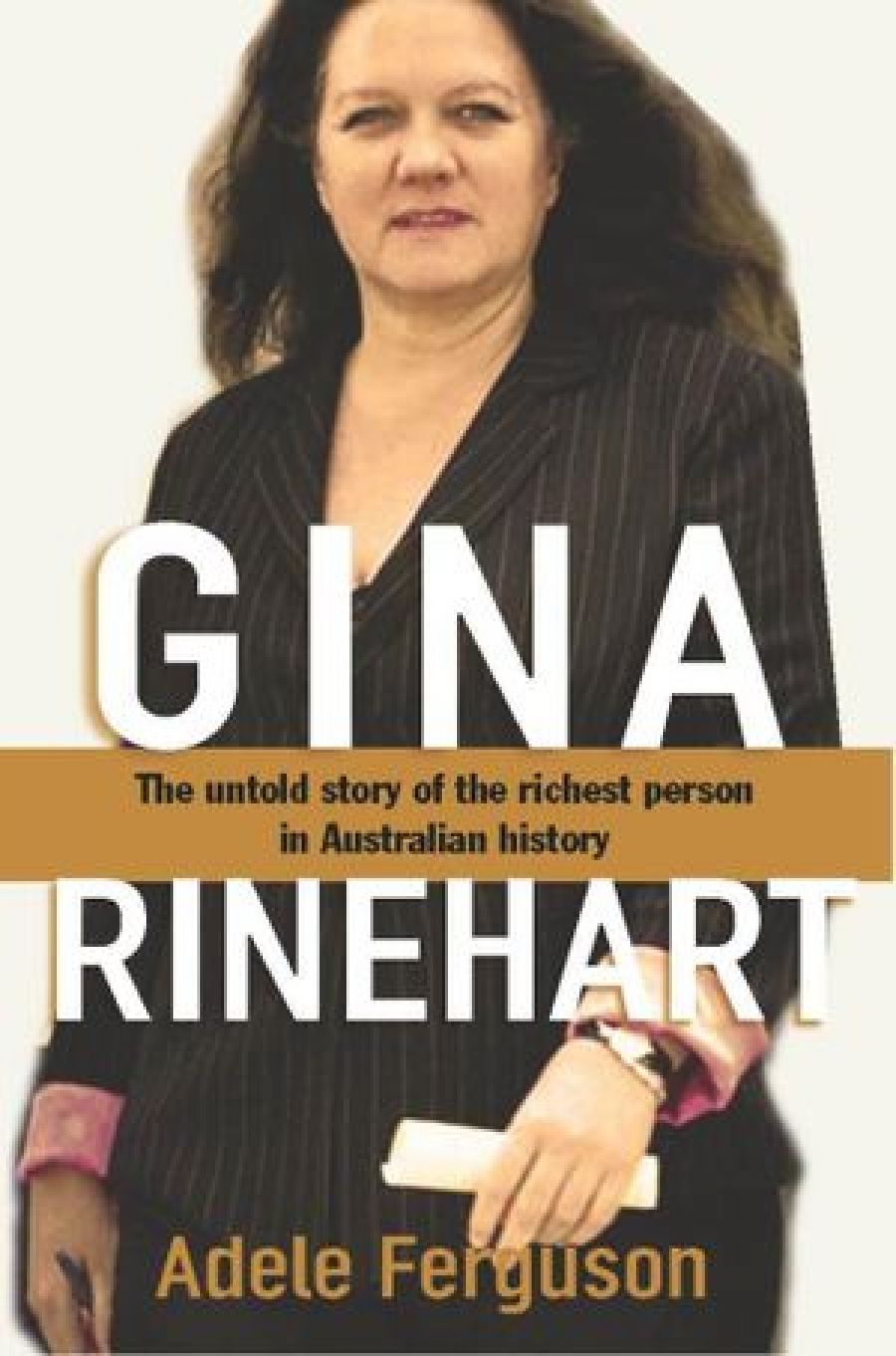

- Book 1 Title: Gina Rinehart

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Untold Story of the Richest Person in Australian History

- Book 1 Biblio: Pan Macmillan, $34.99 pb, 480 pp, 9781742610979

- Book 2 Title: The House of Hancock

- Book 2 Subtitle: The Rise and Rise of Gina Rinehart

- Book 2 Biblio: William Heinemann, $34.95 pb, 381 pp, 9781742756745

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_SocialMedia/2021/Dec_2021/META/9781742756745 copy.jpg

What she has done, when bullying and manipulation failed, is to face down her children in court over their share of the fortune. It is not the first time Gina has litigated her way into the headlines. In 1983 she bizarrely hired the Filipino exotic Rose Lacson as house-keeper to her recently widowed and lonely father, Lang. Rose soon extended her duties to include all home comforts, and Lang was happy. Gina was not, and even less so following her father’s death in 1992, when she began pursuing Rose through the courts to reclaim millions that the formerly frugal and knockabout Lang had lavished on Rose in a flush of nouveau riche excess. In the process of crushing Rose, Gina bankrupted her father’s estate so that his legacies to various family members and loyal staff were dishonoured. The assets ended up in Hancock Prospecting, controlled by Gina.

Lang, Gina, and Hope Hancock in 1962She did not stop there and earned her stripes as a relentless litigant in no fewer than fifteen major stoushes against business associates and rivals, according to Debi Marshall. These include going after assets held by the children of her father’s former partner Peter Wright. Marshall describes this as a case of taking her half of the lollies (as per an agreement between the original partners) and wanting half of the Wright heirs’ share too. Not on Marshall’s list but described by Adele Ferguson are the lengths to which Gina went in order to recover the New York apartment of her late husband Frank Rinehart’s mistress. The woman had lived in the apartment for years and believed that she owned it.

Lang, Gina, and Hope Hancock in 1962She did not stop there and earned her stripes as a relentless litigant in no fewer than fifteen major stoushes against business associates and rivals, according to Debi Marshall. These include going after assets held by the children of her father’s former partner Peter Wright. Marshall describes this as a case of taking her half of the lollies (as per an agreement between the original partners) and wanting half of the Wright heirs’ share too. Not on Marshall’s list but described by Adele Ferguson are the lengths to which Gina went in order to recover the New York apartment of her late husband Frank Rinehart’s mistress. The woman had lived in the apartment for years and believed that she owned it.

Continuing on a well-practised cold streak, Gina strives to airbrush from history those who helped her father. While celebrating Lang’s memory and the Pilbara iron ore discovery that changed the Hancocks’ and Australia’s fortunes, she is determined to take credit for being a better businesswoman.

What forged this powerful personality? Both biographers indicate that in grooming Gina as a ‘mini-me’, Lang created something bigger than both of them, such that Gina could say as a young woman and thus far stand uncorrected: ‘Whatever I do, whatever I do, the House of Hancock comes first. Nothing will stand in the way of that. Nothing.’ Underpinning that declaration is a belief in rampant free enterprise, less government, development of Australia’s North-West, and, above all, ownership of a Hancock mine. Lang’s wealth was built on royalties from finding and selling tenements to mining companies. The dream shared with Gina of actually owning a mine is now within reach. But to realise it she must raise about $7.2 billion, and she needs every cent, including the handy $2.4 billion residing in the family trust. Hence the source of the latest tangle with three of her four children, who, not unreasonably, have their own plans for the trust dividends bequeathed by their grandfather.

All is explained to varying degrees by Marshall and Ferguson. Marshall, as the author of an earlier Lang Hancock biography (2001), spends more time on the family’s origins, describing tough and hardy antecedents who pioneered Western Australia’s remote and empty North-West. While farming the family’s 30,000 acres and mining asbestos at nearby Wittenoom (the first Hancock and Wright venture), Lang discovered the biggest iron ore deposits ever found in 1952, two years before Gina’s birth. Yet it took another decade of persistently lobbying state and federal governments to overturn an embargo on exporting iron ore, then to secure a deal with the mining giant Rio Tinto that gave Lang and Wright a 2.5 per cent royalty on every tonne of iron ore exported from the Hamersley Ranges. Lang was already a tough, strong-willed, and determined individual; Marshall describes how the challenges magnified these qualities.

Young Gina, Lang’s only child – his apprentice and companion – absorbed it all. When she was four, the family moved to Perth where Gina attended St Hilda’sAnglican School for Girls as a weekly boarder. Marshall describes her isolation and reserve at school, but Ferguson explains it. While her peers were allowed only three exeats a term, Gina came and went at will. She was the only girl with a television set in her room, and even the headmistress commented on Gina’s iron will and her parents’ indulgence. Envy and special treatment would set her apart, such that she never quite fitted in or bonded with her school fellows. Spending time with her father – on the family farm, in the Pilbara, interstate, and overseas – she soaked up his views on mining, interfering governments, and procrastinating politicians. During her formative years, Gina never got close enough to anyone for anything other than the House of Hancock doctrine to take hold.

Besides, it was all so exciting – a childhood like no other. Gina accompanied her father on frequent overseas business trips, sitting in on negotiations and meeting world leaders, politicians, and company leaders. How could she not think she was special? Not surprisingly, she idolised Lang.

A Bachelor of Economics at Sydney University provided little scope for exploring other ways of thinking and being. Dismissing university as a socialist kindergarten and a waste of time, Gina dropped out and went to work for Hancock Prospecting. Cue more exposure to Lang while producing two children with her first husband, Greg Milton, before outgrowing him.

Enter Frank Rinehart. Thirty-seven years her senior, a more sophisticated and urbane version of Lang, with a sound knowledge of both mining and the law, Frank topped the Harvard Law School and went on to be convicted for criminal tax fraud. He alone made any impact on the mould cast by Lang. While Ferguson devotes some space to his influence on Gina and her children, two of whom they had together, Marshall hardly mentions Frank beyond registering Lang’s disapproval. Yet according to Ferguson they were happy, and, more importantly, the combative Frank gave Gina a taste for litigation. If Lang forged her ruthless behaviour, Frank (who died suddenly in 1990) provided the armoury with which to execute it.

So much conjecture swirls around Gina Rinehart, particularly in Perth, where everyone knows everyone else. How much easier must it have been for the two biographers who spent months investigating her on her home patch. Yet only Ferguson comes close to suggesting what has shaped her and driven her to wealth and prominence, while providing some context for what it means to be Gina. Gina, of course, wouldn’t speak to either biographer unless she had editorial control.

While using some of the same sources and research material, Marshall complains about the legions too wary of Gina’s influence to be interviewed. She relies heavily for information and clarity on an anonymous mining source. Ferguson’s book is richer for its many telling anecdotes (including news of Bob, Gina’s older companion of the past decade), a range of colourful sources, and her details of the intense filial relationship and the rift that fractured it.

The point of a biography is to get to the essence of the subject. Marshall concludes that Gina is the quintessential poor little rich girl who, not being the boy her father wanted, became tougher and more effective than any man. Ferguson paints a more nuanced portrait of a life abnormally filtered and focused, yet exaggerated at every level. While Lang was pugnacious and meat-axe crazy enough to suggest exterminating half-caste Aborigines and mining with small nuclear bombs, he had warmth and charm. On the evidence of her biographers, his daughter emerges as an unevolved, unsocialised, over-indulged brat programmed to defend and expand the House of Hancock above and beyond what she was heir to and against all comers. Interesting, yes, compelling, no, and definitely not someone with whom you would care to break bread.

Comments powered by CComment