- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Robert Drewe’s first memoir, The Shark Net (2000) – an account of ‘memories and murder’ – opens in the transforming ‘different sunlight’ of a courtroom, a light that seems ‘harsher, dustier, more ancient looking’, making the figure in the dock somehow ‘uglier, smaller’, ‘like a criminal in a B-movie’, the very ‘stereotype of a crook’.

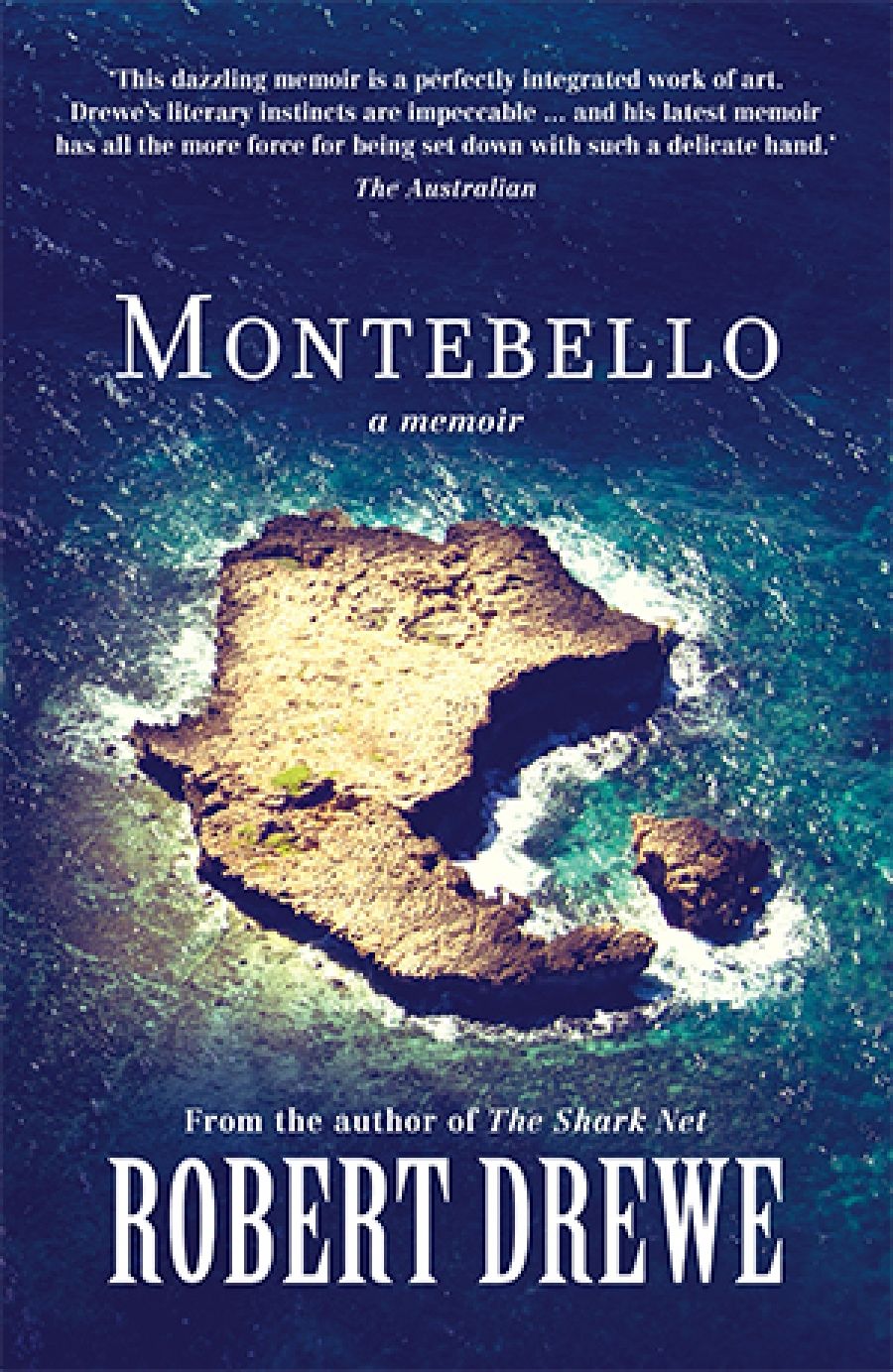

- Book 1 Title: Montebello

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $29.99 pb, 291 pp

Montebello, his second memoir, opens with a veritable volley of deliberately deployed stereotypes. It is ‘that fabled occasion, a dark and stormy night’, and Drewe – though peacefully crooning ‘Blueberry Hill’ to his youngest daughter, Anna, above the howling of a cyclonic storm – is suffering through a kind of ‘genuine self-awareness’ that is as tumultuous and potentially destructive as the battering rain and hammering winds. ‘I could either plummet to the depths or shape up, brush myself down, pick myself up, pull my finger out, turn a frown upside down. Basically, get a grip. The odds at that stage favoured plummeting.’

This is the Robert Drewe who, many years earlier, on his twenty-first birthday, three years married and with one child, had headed east. Now, about as far east as he could get without actually inhabiting the sharky waters off Byron Bay, he is making a meal of killing a brown snake that has invaded his ‘rented cottage on the cliff edge’. His weapon of choice – the only one quickly available – is a barbecue spatula, which turns out to be not ‘as sharp, weighty or deadly’ as he had hoped and with which it takes a long time, ‘years, decades it seems’, to subdue the thrashing snake.

Typically, Drewe recognises the unintended literary provenance of his parodic re-enactment: ‘It’s not an AustLit snake. It’s not the Snake of Capitalist Greed of Henry Lawson’s poetry, or hardly even the Snake of the Threat of Female Otherness of Lawson’s Drover’s Wife … If anything, it’s the Snake of Male Dazedness and Foggy Indecision.’ But for all his satiric and self-deprecatory wit, the snake episode nevertheless is ‘a turning point’.

In his Our Sunshine (1991), Drewe’s imagined Ned Kelly interprets the violence of a storm ‘as an omen, a clearing of the sullen air, fresh days ahead … Everything … is … on our side.’ Like his version of Kelly, Drewe feels once more ‘in control of events … The sky, the foliage and the fauna appear sharply etched and the whole passage of the day seems more optimistic’ as the storm clears. Not quite an epiphany, but a strange and welcome calm. And so he forces himself ‘to function’: that is, to write. A collection of stories (The Rip, 2008), fortnightly columns in The Age, edited collections, and Montebello get under way. The latter, with its fascinating ‘Islomania’, its skilful weaving of research with imagination, its dark nuclear secrets and their gradual, mordant unravelling, would seem to have a provenance quite different from that of both the earlier memoir and his novels and stories. But as that opening sequence of storm and snake and small vulnerable daughter immediately foreshadows, Drewe’s overarching themes are love and danger.

The Montebello story – the historical record threaded by the elements of Drewe’s imaginative encounter with it – enters the narrative unannounced, in medias res, in the form of the Tom Welsby, the squat, lumbering landing barge on which, one sudden midnight, he embarks and heads for the Montebellos. The story of his slow, partial recovery from ‘adrenaline surges of anxiety’, as he seeks to recover both his creative momentum and his equanimity, continues in a different register.

It was difficult to explain to my companions why I was aboard the Tom Welsby with them this night bound for a barren Indian Ocean archipelago of uninhabited, government-controlled islands with a notorious past. So I didn’t try. I hoped the trip would amount to something, even though the what exactly? wasn’t clear to me. It wasn’t only that I’d returned to the original backdrop of my writing – the West Australian coast – and that I was probably an islomaniac as well (I’d only recently heard of the term islomaniac – a fascination with islands), it was that ever since I was nine years old I’d been alarmed by the Montebello Islands.

The trip does ‘amount to something’. As a project designed to bring about ‘animal translocations’ to islands that ‘had endured the greatest negative impacts of any place on earth’, it is a triumph. ‘Fish jumped and flopped and fled in the lagoon nearby … immigrant animals were thriving and enthusiastically reproducing.’ Sitting next to the helicopter pilot on the flight out, Drewe scans the whole archipelago. ‘Into the deep indigo pit of the first bomb blast off Trimouille Island, from the open sea swam twenty or thirty turtles … swimming in from the Indian Ocean to lay their eggs, as they had always done’.

But the most resounding triumph is Drewe’s alone. The man who, on the edge of despair as he sang to his daughter over the shouting of the storm, and desperately fought off the brown snake before it reached her room, was ‘for the moment … saved’ by ‘overwhelming, indescribable love’. Love – for his children and, as the narrative develops, for Tracy, with whom he rekindles an old friendship and then finds a new love – animates much of what he thinks and feels as he struggles, with growing success, to cope with the island, his role in the project, and the insistent calls of memory, imagination, and art. Although it has many faces and shades, Montebello is at heart a moving and profound love story.

As for the danger, there is some on the island but much in his memory. Shark attacks, drowning, suicide, murder, and assaults stud the life of a news journalist. But some of these – especially the death by drowning of a boyhood friend, the apparently targeting onslaught of a Great White Shark, and the deadly irony of the ‘Harbour Story’ told to him as the result of a chance acquaintance on the eve of his departure for Montebello – haunt him for years and infiltrate his creative imagination, almost against his will. Not to mention, of course, his half-comprehending boyhood obsession with the terrors of the nuclear bomb.

Just as Montebello is a testament to, and is nourished and formed by, Drewe’s human, moral, and artistic concerns, it is also typically witty, fascinated by the curious, the bizarre, and the eccentric. Memories of writers’ weeks, journalists, news rooms, and academics provide a string of anecdotes. ‘This was Surry Hills. This was the Invicta Hotel, where my editor – nicknamed Romney Marsh for his woolly yellow hair and sheep-baa laugh – groped pretty young female journalists on their first day on the job and settled arguments by pouring beer on his reporters’ heads.’ Or, ‘Lifestyle [in mid-1970s Sydney] equalled literature. Lifestyle had no place for children. Lifestyle meant sex. English department lecturers across the land were immensely flattered at the sexual attention and remained so for the next twenty years.’

Amid such exuberant abundance of story there are no longueurs, but there is some indulgence. The ‘Prison Diary’, for example, though interesting in itself, seems less able to claim its relevant place in a narrative that is otherwise distinguished by tight and reverberant interconnections.

This is a splendid memoir with many moods – delicate, tough, ironic, compassionate – that are beautifully controlled and paced. Many episodes end with a perfectly judged ‘dying fall’, as does the whole work, with the lovers, reunited at last, cycling slowly home, ‘side by side and talking quietly’.

Comments powered by CComment