- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1959, as part of the Rex Nan Kivell collection, the National Library of Australia received a remarkable volume of First Fleet paintings. Inscribed Birds & Flowers of New South Wales, Drawn on the Spot in 1788, ’89 & ’90, it comprises 100 watercolours of birds, flowers, fish, animals, and a small number of Indigenous portraits, and was owned by Captain John Hunter, one of the key naval officers of the First Fleet, who painted most of the watercolours. A substantial publication about the sketchbook, edited by John Calaby, was produced by the National Library of Australia in 1989, but critical new information came to light in 2005 when the Library acquired the Ducie Collection, comprising fifty-six watercolours attributed to George Raper, midshipman on board HMS Sirius. Previously unknown to art historians, Raper’s paintings proved to be the source for many of the images in Hunter’s sketchbook. Linda Groom, then-curator of pictures at the Library, had the enviable task of researching and publishing on Raper’s work (First Fleet Artist: George Raper’s Birds & Plants of Australia, 2009). A Steady Hand may be regarded as the inevitable sequel.

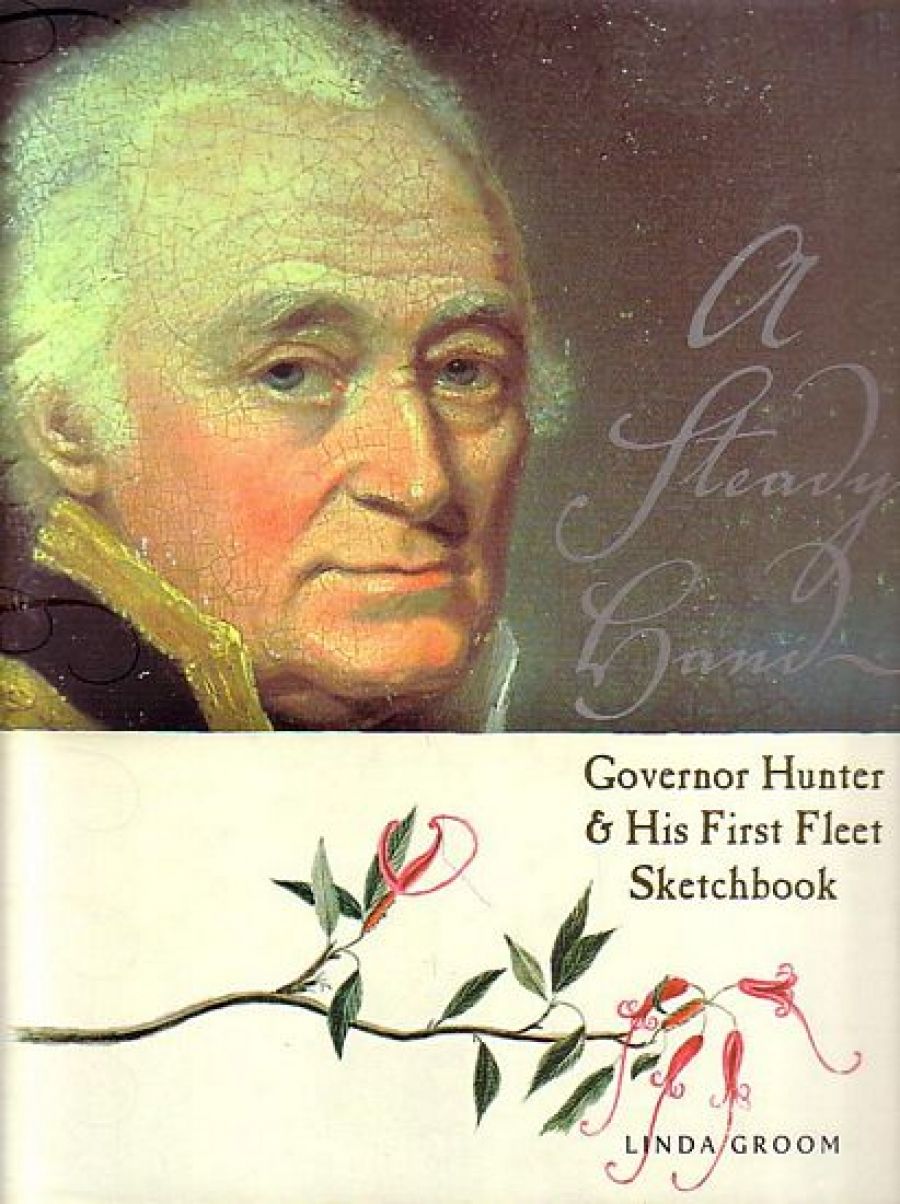

- Book 1 Title: A Steady Hand

- Book 1 Subtitle: Governor Hunter & His First Fleet Sketchbook

- Book 1 Biblio: National Library of Australia, $49.95 hb, 235 pp, 9780642277077

As the subtitle indicates, and following the format and design of First Fleet Artist, this book is divided almost equally into an illustrated biography and full-page, to-scale reproductions of the sketchbook. Groom’s in-depth research covers the facts of Hunter’s life, and explores his personality, achievements, and controversial governorship (1795–1800). Born in 1737, he began in the Royal Navy, aged sixteen, and his long service included time in Canadian, West Indian, and American waters. Appointed in 1786 to the Sirius, flagship of the First Fleet, Hunter was second in command of the new settlement at Port Jackson, under Governor Arthur Phillip. His speedy circumnavigation of the globe to collect supplies from Cape Town in 1788–89 kept the colony from starvation, yet his skilful seamanship failed to save the Sirius – one of only two ships in the colony – from shipwreck on Norfolk Island. His skills were required once again on his difficult voyage back to England, where he published An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island (1793) for an eager European audience. Two years later he returned to New South Wales as the second, long-delayed governor to find the colony much changed and power firmly in the hands of the military settlers. Frustrated by this and by ill-informed commands from the distant secretary of state, Hunter was recalled to England in 1800. He died an admiral in 1821.

Hunter was recognised by colleagues as an expert surveyor and maker of maps and coastal profiles, for which purpose naval officers received training in draughtsmanship. Being principally at sea, he had little opportunity to develop skills in other forms of drawing. In his Historical Journal, he wrote: ‘there are a great variety of birds in this country; all ... are cloathed with the most beautiful plumage that can be conceived; it would require the pencil of an able limner [artist] to give a stranger an idea of them.’ He clearly did not regard himself as such. It is noteworthy that illustrations of Australian flora and fauna are absent from his Journal, unlike the earlier publications of Phillip (1789) and John White (1790), both of which catered lavishly to the huge interest in ‘non-descript’ species. However, the first published representation of a wombat, and one of the earliest of a platypus, were based upon drawings by Hunter while governor, appearing in David Collins’s An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales (Vol. 2, 1802). The crudity and inaccuracy of these images suggest that Hunter was, actually, pretty awful at natural history images when he was not copying the work of others. A Steady Hand is possibly not a very apt title. Unless as-yet-undiscovered material proves otherwise, his sketchbook was an anomaly, but an undeniably charming one. His watercolours are endearingly naïve, with what can now be recognised as personal touches added to his interpretations of Raper’s, and possibly others’, paintings.

A general overview of the sketchbook itself is presented in a dedicated chapter within the biography, describing the format, comparing examples of Raper and Hunter’s work (Hunter’s always being the simpler and less accurate), evident differences, and Hunter’s painting technique. Copying was then an accepted form of visual transmission, and Raper may have been flattered that his commanding officer wished to replicate his watercolours for, it is presumed, his own personal record.

The relationship between artists and copyists within the colony, back in England, probably also in India, and possibly even Batavia, is a fascinating one, and warrants ongoing research (as with the unidentified artists known as the Port Jackson Painter and the Sydney Bird Painter). Often the physical components of the works provide critical evidence, and it is a great pity that less information is provided by Groom about the sketchbook than was provided by Andrew Sayers in the 1989 publication: watermarks, for example, or the fact that Hunter had access to only eight pigments, which inevitably limited his colouring. A physical description to introduce the reproductions would have unified information included elsewhere about the size, layout, binding, and minor digital cleaning of the images (admirably acknowledged but unnecessary in my opinion, given their surprisingly good condition). These reproductions give the confusing impression of a facsimile, which encourages the assumption that these watercolours are on facing pages rather than, principally, on the recto. A list of plates would have been useful, and, with the new evidence available from the Ducie Collection, an appendix listing connections between known Hunter and Raper works (in the National Library and the Natural History Museum) would have assisted researchers.

A Steady Hand is in many ways an elegant, enjoyable, well-researched, and well-written book, pleasurable to hold and to read. The images are treated respectfully, rarely overlapped or skewed (a regrettable current trend for colonial publications), and subtle choices enhance the physical experience, such as the use of laid paper (which was standard in Hunter’s time) for the endpapers. Groom has undertaken extensive research into Hunter’s life; but, given that this is the first publication to examine Hunter’s work in the light of the Ducie discovery, it is a pity that the art-historical analysis is not more expansive. A fine publication for the interested general public, it misses the opportunity to provide facts to assist scholars, and to explore these wonderful watercolours not only within Hunter’s life, but also within the body of natural history watercolours made during that intense first decade of Australian colonial history.

As an example, the strict alternation of bird then flower watercolours copied into the first two-thirds of the sketchbook was clearly a decorative and considered arrangement – this was in fact not a sketchbook, for impromptu studies, at all. Was it a consecutively worked book (as Groom suggests) or largely done during a period of concentrated painting? Could it possibly have helped pass the eleven months spent waiting on Norfolk Island, one of the few times in Hunter’s life when he would have had time on his hands?

Images

John Hunter, King parrot (Alisterus scapularis), c.1788–90, watercolour (National Library of Australia)

John Hunter, Wa-ra-ta, c.1788–90, watercolour, (National Library of Australia)

John Hunter, Small fish of Norfolk Island, c.1790, watercolour (National Library of Australia)

John Hunter, Man of Duke of York’s Island, c.1791, watercolour (National Library of Australia)

Comments powered by CComment