- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cultural Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Colin McCahon was a prominent late-modernist New Zealand painter who temporarily disappeared while visiting the Sydney Botanic Gardens on 11 and 12 April 1984. As Martin Edmond relates, ‘Colin went off to the toilet but didn’t return’, and subsequently ‘spent 28 hours lost on the streets of Sydney’. When discovered, ‘he could not say who he was, carried no identification and seemed disoriented’. This largely speechless disorientation persisted until McCahon’s death.

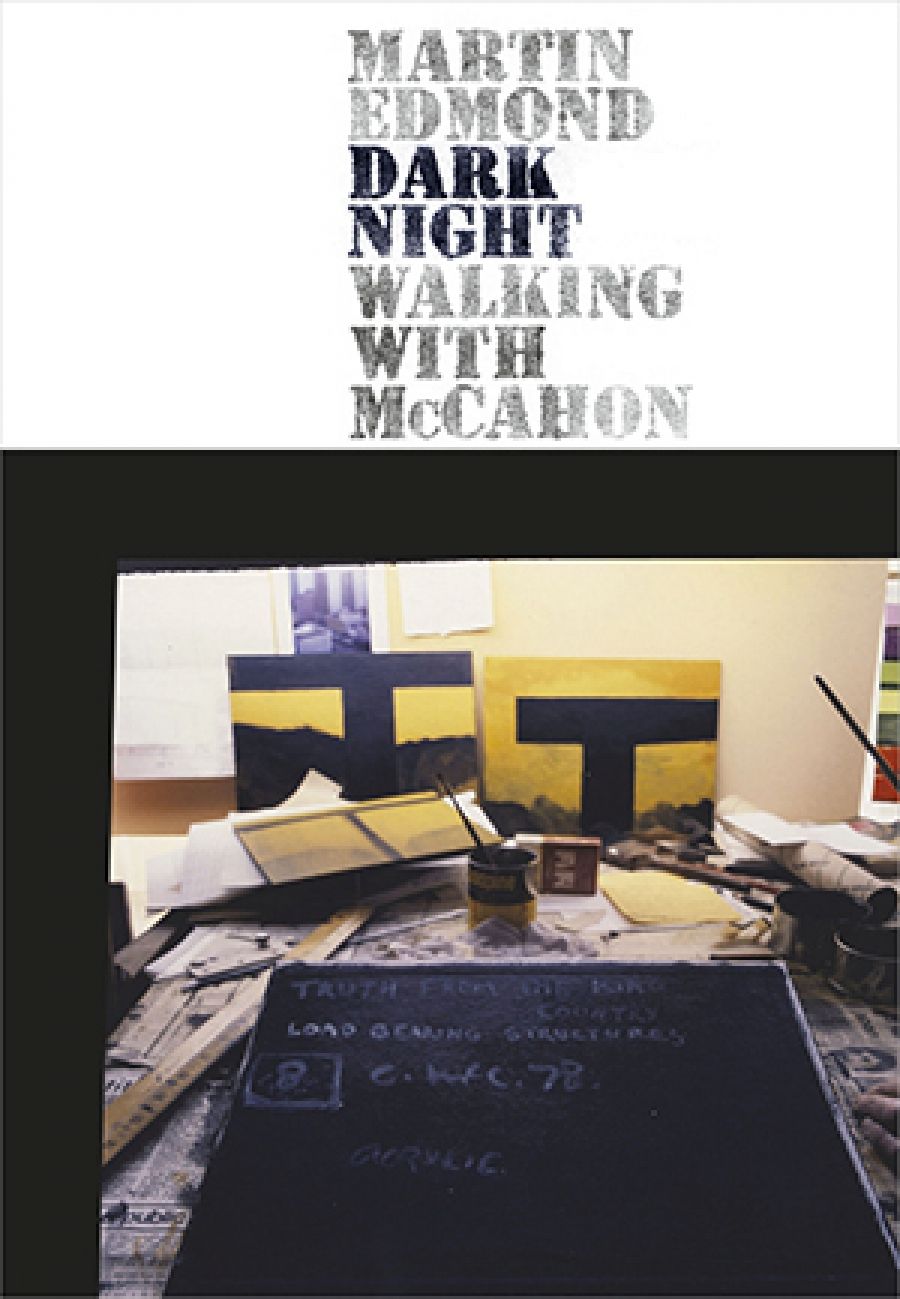

- Book 1 Title: Dark Night

- Book 1 Subtitle: Walking With McCahon

- Book 1 Biblio: Auckland University Press (Inbooks), $34.99 pb, 198 pp, 9781869404833

Such is the point of departure for Edmond’s latest literary quest. Dark Night: Walking with McCahon follows hard upon a series of books that have garnered high critical praise, if not popular attention – the most notable of these perhaps the magnificent Luca Antara (2006) and the deftly handled The Supply Party (2009) – and more than matches these in imaginative and emotional intensity, formal ingenuity, elegance, and insight. Dark Night is a meditation on the artistic life viewed through the biographical lens of one of last century’s most intriguing and serious painters, by one of today’s more innovative and compelling writers. Compounding its brilliance is the sheer intimacy of Edmond’s engagement with McCahon.

By comparison, The Supply Party is less satisfyingly opportunistic. In that book Edmond has some good ideas and interrogates them with uneven results. Dark Night, on the other hand, seems the product of a lifetime’s germinating interest and contemplation, compressed into a smaller physical space – primarily around Sydney – which intensifies the representation of, and speculation about, Edmond’s and McCahon’s inner worlds. Even the concluding journey to New Zealand takes on the aspect of a re-immersion into an inner, personal, and imagined history instead of an expanding external template.

Edmond describes the inception of Dark Night in its opening chapter:

I thought and thought about it and at some point conceived the idea of replicating that lost journey – not in search of authenticity, nor documentary truth, nor even simple verisimilitude, since all of these were by definition impossible. Rather I wondered if I could arbitrarily choose a route and along it find equivalents for the fourteen Stations of the Cross? And, further, if I spent a night alone in Centennial Park, as McCahon had done, might the events or non-events of that sojourn be configured in terms of the Dark Night of the Soul as written by sixteenth-century Spanish poet and monk St John of the Cross? McCahon several times mentions John of the Cross as an exemplar; and made many paintings of the fourteen stations.

Edmond here foreshadows the basic structure of the middle two chapters of Dark Night. He also openly declares and justifies the formal restraints employed. But in truth the reader has already been subjected to inventive reportage and speculation in the preceding descriptions of youthful encounters with McCahon and his work. Dark Night is, therefore, a fictional speculation prefigured by inventive observation.

The genre is hybrid, although Edmond implicitly refers to his own work as ‘literary non-fiction’, to which we might add Walter Benjamin’s notion of the ‘chronicler’, an inventive storyteller who produces speculative and instructive ‘versions’ of unverifiable histories. Edmond demonstrates, via a kind of literary performance, that connections can be made between objects, places, art, history, and people that deepen our relationship with them and enrich experience in multitudinous ways. This exhibits an anti-entropic world view, except in the resistance to arbitrary formal and generic categories that have been superimposed over writing practices and consumption – a happy instance where the collapse of categories enriches form and content instead of disintegrating them.

Edmond’s point of departure for such speculation is a metaphorical bridge between the drive and capacity for complex communicative expression – or art – and the complete loss of that drive and capacity. We learn that, ‘The toilet block [where McCahon disappeared] had two entrances, two exits; [McCahon] must have gone in one door and out the other.’ Edmond takes this fact and, drawing from the prominent formal and thematic content of McCahon’s paintings (where metaphors of bridging as communicative symbols abound), turns it into a running theme. The toilet morphs into a ‘portal’ or numinous space linking separate worlds: in this case, McCahon – a sentient consciousness super-adept at symbolic communication – is transformed into an almost insentient (un)consciousness deprived of basic language. And this is where things become interesting: for the purpose of his exposition, Edmond seeks to perform McCahon; to embody his subsequent adventures, on the one hand, but also to articulate those adventures in a way that McCahon never could. In one door, out the other; enter McCahon, exit Edmond; and so the quest begins.

Although Edmond is chiefly concerned to embody McCahon, Dark Night is by no means limited by its primary subject matter. Readers are warned early on that the work is staged as a literary performance – experimental and experiential – and because of this it is open to all kinds of incursions and digressions. Bringing this into tension, however, is the revelation that what manifests in the telling as a single pilgrimage is in fact the product of multiple pilgrimages.

A great strength of Edmond’s narrative is his remarkably empathetic engagement with the various marginal people encountered along the way. Stretching the limits of normalcy and challenging social and symbolic orders merely by existing, tramps, convicts, transvestites, prostitutes, rent boys, nocturnal bats, corpses, ghosts, and the parallel worlds they occupy are all linked in Dark Night, via a web of associations, to an originating ‘abject space’. This abjection manifests interchangeably as public urinal, purloined mother, painting, and poetry.

The first ‘Station of the Cross’ provides a general template for those that follow. Beginning with a history of vegetation in the gardens and its many visual and purposive transformations, followed by a gentle disquisition on nocturnal bats, creatures ‘revelatory of stories of darkness from old Europe’, Edmond soon shifts to ground zero: the former site of the public urinal from which McCahon failed to return decades before.

We learn that public toilets remind Edmond of watching rugby with his father as a boy, seeing men crammed alongside each other at half-time, urinating in voluminous connecting streams. This association branches into a memory Edmond has of his former primary school toilets, which stimulates a recollection of the ‘bizarre’ stories told among the boys about female genitalia and sex.

The final association is grim and incorporates all of those preceding it: a fusion at once suggesting deliberate or compulsive displacements of a central, powerful, and haunting recollection. Edmond writes: ‘It was either behind the adjoining girls’ toilets at Greytown Primary, or else behind the nearby bike sheds, that my sister, aged nine, was raped one afternoon by a youth who’d escaped from a mental hospital.’ Then: ‘All of these confronting, disreputable or sinister associations seem to gather in that dim, malodorous interior into which McCahon stepped through one door and, thoroughly and permanently changed, out the other.’

Such is the general pattern of each episode, where Edmond employs some combination of observation; marginal but interesting facts; linkages between these and McCahon; personal autobiographical associations; more unifying links to McCahon; and direct speculation. Edmond follows the strands of associative logic with such clarity and insight that this fairly explicit pattern is never rendered tedious.

With Dark Night, Martin Edmond stages a beguiling and affecting literary performance.

Comments powered by CComment