- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Venero Armanno’s latest novel begins implausibly. A young man is troubled by a recurring dream about a faceless, one-armed, blob-like creature being throttled by someone wearing a pale blue shirt. This troubled dreamer is Mark Alter (the unsubtle last name underlines one of the book’s central concerns), a university drop-out estranged from his parents and now leading a grungy existence in a seaside shack. The cavalcade of unlikely events starts on page four. After watching a so-called ‘cheap slasher film’ at his local cinema, Mark decides to turn his nightmare into a screenplay about ‘a shape-shifting demon from the Id’. The title? No-Face, of course. Mark sends his work to various producer types. One of these bigwigs replies by telephone (this is a novel where implausibilities are piled very high indeed) and accuses Mark of plagiarism. According to this famous producer, No-Face has ripped off the obscure novel Black Mountain, written five years before by the equally obscure Cesare Montenero.

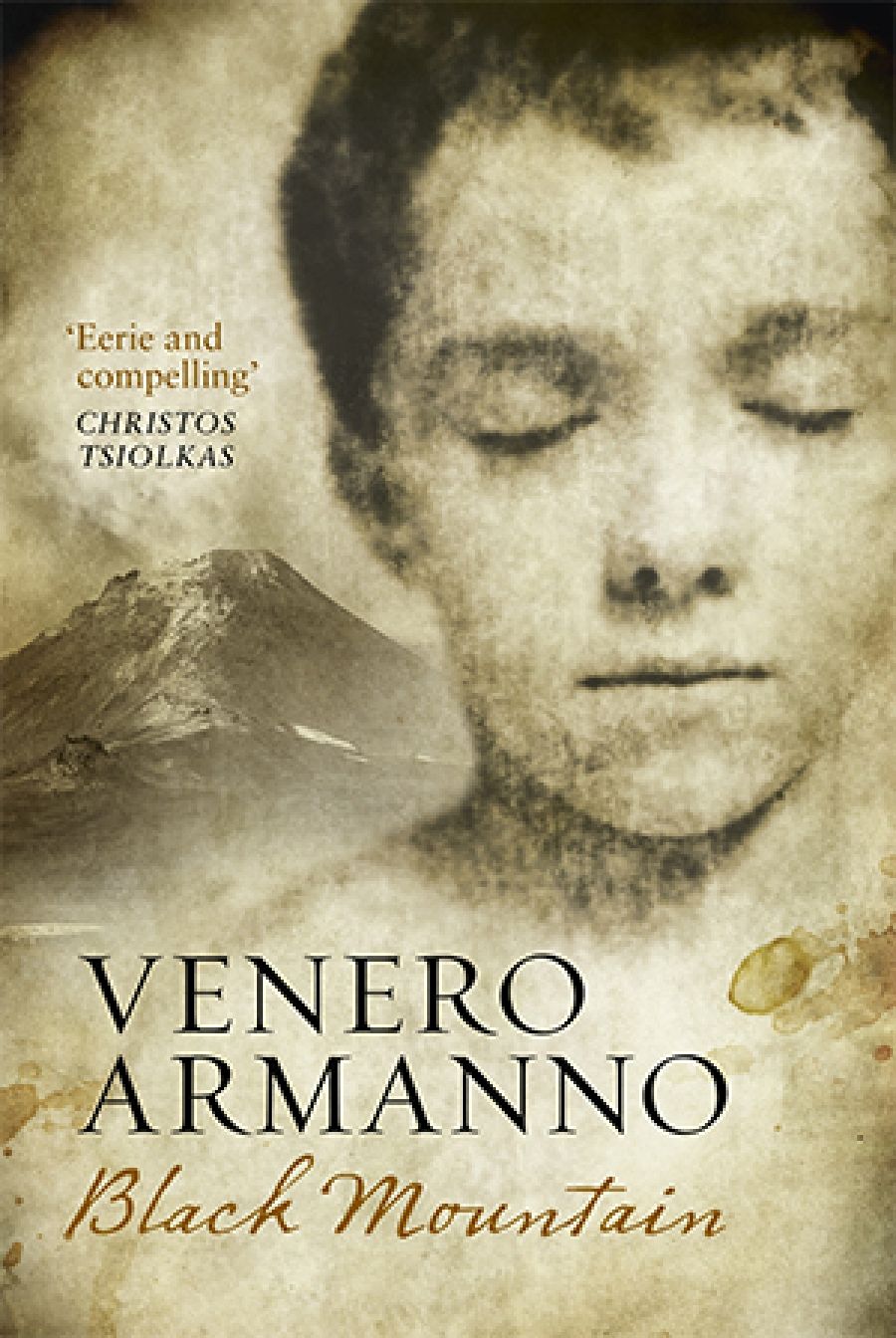

- Book 1 Title: Black Mountain

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $29.95 pb, 279 pp, 9780702239151

Curiously, Mark is more ashamed by this accusation than incensed. Thanks to the Internet, he learns that Montenero published two novels in Italy before the war. A copy of Montenero’s Black Mountain is eventually tracked down by Mark’s local library and, sure enough, it describes a faceless, one-armed, blob-like creature being throttled by someone wearing a pale blue shirt. Mark is, to say the least, violently perplexed by this narrative similarity: ‘he felt as if an unseen fist had punched him in the belly and a great hand had slammed his head against a wall.’ Even worse, perhaps, he is now ‘all twisted up inside’. Naturally, he tries to contact Montenero. At first he is thwarted by the stonewalling tactics of the old novelist’s publishers (that much seems plausible). Then, out of the blue, a stranger telephones and Mark ‘knew, instantly, without doubt, that this was Cesare Montenero’. A cryptic conversation ensues, with a few Sphinx-like riddles about wanting to live forever. A fortnight later, Montenero’s publisher coughs up its client’s rural address: ‘as if liberated from chains, Mark immediately readied his backpack.’

Montenero owns a mansion, of course. When Mark arrives, he finds no sign of life apart from a trio of tail-wagging dogs (though these are later whisked off to a pet motel, never to be seen again). The back door is unlocked (you knew that already, gentle reader), so Mark takes a tour. Property agents may be interested to learn that the house has a walk-in pantry, a formal dining room, a sunroom, a vast study, ‘two glistening bathrooms’, and ‘a well-appointed master bedroom with an ensuite’. After a night ‘curled up in the deep sofa’ (so deep, it seems, that he is in it, not on it), Mark spends the next day exploring Montenero’s lush estate. By another remarkable coincidence, he is impelled to start digging around a tree that resembles the faceless, one-armed, blob-like creature of his nightmare. This excavation uncovers a box containing a manuscript that seems meant for Mark. The next two hundred-odd pages are taken up by this novel-within-a-novel: namely, Cesare Montenero’s rags-to-riches life story.

As a boy, Montenero is owned by a series of increasingly brutal Sicilian masters who work him to the bone in the island’s hellish sulphur mines. Miraculously, he escapes, only to be pursued up the slopes of Mount Etna by his furious, gun-toting enslaver. Another miracle: he is saved by a mysterious local aristocrat, with the timely help of a blob-like guardian spirit. Predictably, the aristocrat adopts the bullet-ridden boy, schooling him in the palazzu’s ‘voluminous library’ and generally introducing him to the finer things in life (music, horse-riding, Fiats). Montenero learns that, like his aristocratic saviour, he is the product of a botched genetic experiment from which he has acquired certain superhuman powers; the two characters also share a literary vocation. The manuscript then whirls through pre-war Catania, Bologna, and Paris, its pages crowded with mad scientists, lavish bordellos, and unconvincing violence. All this, of course, has a particular connection with its putative reader – young Mark Alter, alone somewhere in the wilds of twenty-first-century Australia.

It is hard to know whether Black Mountain is intended as a work of genre fiction, designed for readers who already enjoy fantasy or supernatural themes. Like all fiction, genre fiction succeeds only when its style leads to a willing suspension of disbelief; put another way, a good genre novel is simply a good novel (think Simenon, Highsmith, or le Carré). Black Mountain misses this mark by a very long way. Style, though, is not the only problem here. What is really annoying about the book is its smugness. In one scene, for instance, we see Montenero reading Italo Svevo’s ‘fine novel’ Senilità; it is indeed a fine novel, but why patronise the reader by saying that? Elsewhere, we are constantly told about the aristocratic character’s refined aesthetic taste (though someone should tell UQP’s proofreaders that there is likely no musical composition called The Rites of Spring). Of course, facts hardly matter in this ridiculous book. Nevertheless, Black Mountain occasionally shows signs of wanting to escape the realms of fantasy into an altogether more serious mode (which might also explain the extravagant back cover blurb describing it as ‘a haunting exploration of what it means to be human’). But that sort of escape would need a far more powerful guardian spirit than the faceless blob in Mark Alter’s dreams.

Comments powered by CComment