- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Test cricket and the novel are two pinnacles of modern cultural achievement, long-haul enterprises of intricacy and complexity. Why, then, have the two rarely intersected? It is especially strange given that cricket has arguably had more books devoted to it than has any other sport. Literary-minded cricket lovers will rhapsodise over the prose style of C.L.R. James or the nostalgic elegance of Neville Cardus, but few books about cricket have been fiction, and even fewer of them have been much good. While Joseph O’Neill’s recent Netherland (2008) was a fine offbeat novel that featured cricket, there have been no great works of cricket fiction. Until now.

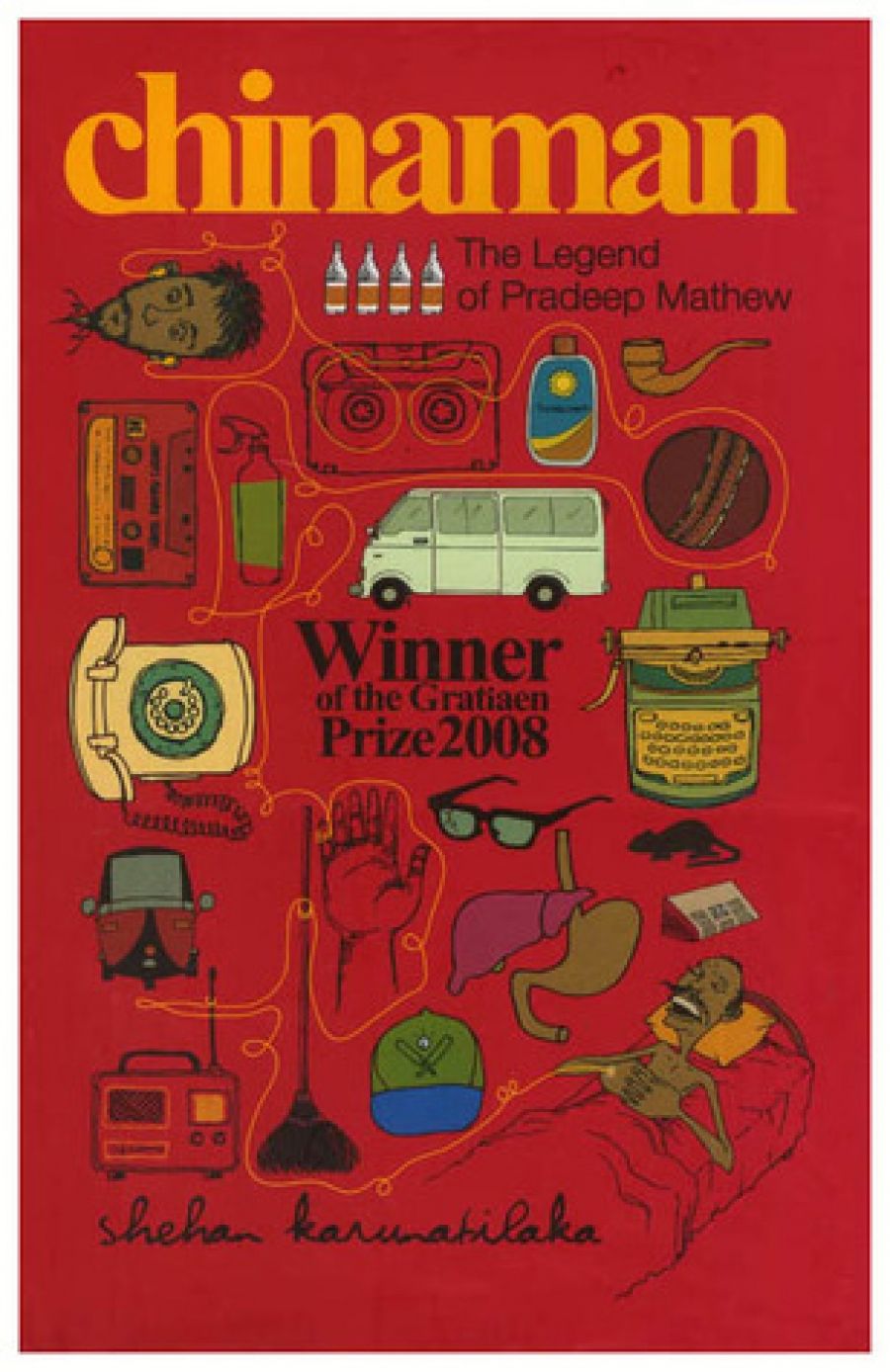

- Book 1 Title: Chinaman

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Legend of Pradeep Mathew

Shehan Karunatilaka’s Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Mathew, which this year won both the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature and the Commonwealth Literary Prize, is possibly the first masterpiece of cricket fiction. Told from the perspective of alcoholic Sri Lankan sportswriter W.G. Karunasena, it is a witty and scabrous novel about both the sport and contemporary Sri Lankan society. W.G. and his next-door neighbour and drinking buddy, Ari Byrd, are cricket tragics, grown men who, when not watching the sport on the television, spend much of their time reliving the highlights of their spectating careers, or compiling best-ever elevens and arguing about them while drunk.

Signed up to produce a series of documentaries on Sri Lanka’s greatest ever cricketers, W.G. decides to begin the book that he has promised to write for decades. However, his body is collapsing because of his drinking. Unless he gives up alcohol, he won’t have long to live; unless he drinks, he can’t write. Also distracting him are the politics of Sri Lankan cricket, particularly the inclusion in his pantheon of Chinaman bowler (a left-arm wrist spinner) Pradeep Mathew. According to W.G. and Ari, Mathew, despite his erratic career, is the greatest Sri Lankan bowler of all time. Yet W.G.’s insistence upon his inclusion meets with considerable resistance from the cricket ‘uncles’ (the generic title for a Sri Lankan man who has reached middle age) who rule the game, while his enquiries about Mathew lead him into dealings with gangsters, cricket groupies, debauched commentators, and grounds-keeping dwarves. All the while he must battle with the internal demons brought on by his love of the grog and his consequent failure as a husband, father, and provider.

This fabulous tale riffs off the true history of Sri Lankan cricket and throws Mathew as a stirrer into the mix. Real characters ranging from Arjuna Ranathunga to Richie Benaud are the targets of Karunatilaka’s biting wit. Part of the pleasure of this book is trying to untangle the mischief of his roman-à-clef. Some characters are simply referred to as GLOBs (great left-handed opening batsmen); others are slightly cryptic hybrids of real cricketers. The plot turns in unexpected and absurd directions as W.G. pursues the enigmatic spinner. In doing so Karunatilaka shows up the paradoxes, idiosyncrasies, and tensions that drive Sri Lankan culture, a place designed for ease that has ended up with a deeply fractured polity and thirty years of civil war. Indeed, the career of Mathew may well be interpreted as an allegory for that of Sri Lanka since its independence from Britain in 1948, a lament commonly expressed by Sri Lankans of W.G.’s generation.

Australian readers will be interested to see how the world views our cricketers, as famous for their abrasive arrogance as for their abilities. The satirising of our commentators is also amusing. Yet this is not so much a novel about the giants of the sport as it is about what it means to be a sports fan. Anyone who has sat down with a copy of Wisden and perused scoreboards and series averages will understand the obsessions of W.G. and Ari. If Chinaman is a tragicomic sporting allegory of Sri Lanka, it is also about the tragi-comedy of being a middle-aged man, for whom following sport can be a huge, if frustrating, compensation for a vanishing life inadequately lived.

Karunatilaka’s background is as a copywriter, and he has a superb ability to capture something via an oblique approach. Take his account of Dehiwala Zoo, which he turns into an emblem for Sri Lanka.

At the zoo, the animals are as shabby as the people looking at them. This was once the largest and finest menagerie in all of South Asia. Alas, the zoo’s great Burgher superintendent migrated along with most of our good ideas to Singapore. Now they have the best zoo in Asia, and Dehiwala is a half-dismantled prison filled with emaciated giraffes and black panthers that look like cartoon pink ones … And even though the price of admission is less than half a pack of cigarettes, I’m sure that vast quantities of money flow into this place and go into building enclosures for biped mammals who wear white sarongs and drive Pajeros.

This caustic wit pervades the whole book. The play between fantasy and cynicism, two distinct responses to the single problem of disillusionment, is superb. Chinaman takes the ‘gentleman’s game’ and reveals it for the political quagmire it is; nonetheless a love for cricket shines through. This is magic realism in a feral mode. If Chinaman were an Australian cricketer, it would be Doug Walters scoring a Test century after a big night on the turps.

Comments powered by CComment