- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

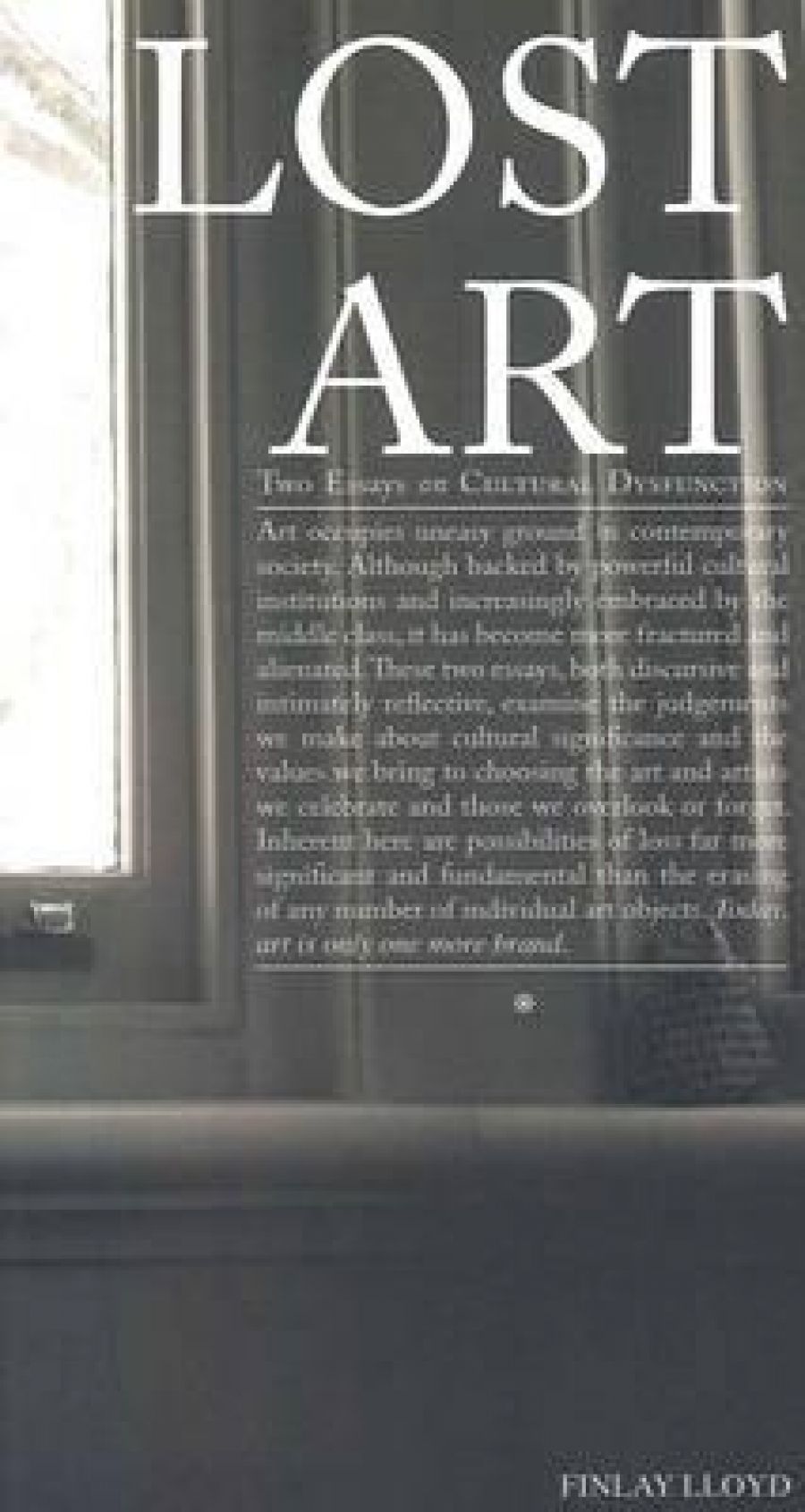

Lost Art: Two Essays on Cultural Dysfunction is an absorbing and lyrical journey through the contemporary art world. Combining a sensibility that is both highly critical and deeply personal, Julian Davies and Phil Day analyse what is celebrated and what is forgotten in an increasingly ruthless and commercial industry.

- Book 1 Title: Lost Art

- Book 1 Subtitle: Two Essays on Cultural Dysfunction

- Book 1 Biblio: Finlay Lloyd, $15 pb, 90 pp, 9780977567768

Lost Art contends that the art world, in a state of dysfunction, is splitting open like a bad wound. Monolithic and industrialised, much of the culture that is produced is left unseen, unheard, obscured, marginalised – or, as Antonin Artaud described Vincent van Gogh, ‘suicided by society’ (le suicidé de la société). With so much loss, how can we keep track of our ghosts? Will most art be categorised as ‘outsider’ or ‘naïve’ in order to clear the path for more ‘professional’ work? Is there more pressure on artists to be professional than artistic? How does this alter our reception of art in the public sphere?

We recall Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s study of creative practice and mental illness, Capitalism and Schizophrenia: The Anti-Oedipus: (1977). The art world has long accepted, perhaps even encouraged, spasms of creative neurosis, and comprehensively dismissed signs of psychosis:

we draw a line between the eventually creative neurotic aspect, and the psychotic aspect, alienating and destructive. As if the great voices, which were capable of performing a breakthrough in grammar and syntax, and of making all language a desire, were not speaking from the depths of psychosis, and as if they were not demonstrating for our benefit an eminently psychotic and revolutionary means of escape.

We make judgements of what is culturally significant in an almost evangelical way, which only rectifies paternalistic conquests of trying to define the world – its people, their work, their illnesses. Davies addresses this in his musings on the reception of Goya’s later work:

Knowledge about Goya, for instance that he was a successful court painter for much of his career who later withdrew to make strange pictures that are sometimes regarded as resulting from illness or mental breakdown, can get between us and the paintings. Information is a tool that frequently comes between looking and understanding, predisposing our judgements to the influence of imposed ideas.

Davies is confounded as to how canons make us realise how much fodder there is. At the Louvre he battles through the crowd to see the Mona Lisa, while Leonardo’s Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, equally extraordinary, goes unobserved.

Equally spontaneous in his approach, Day utilises various bits of visual information: tables, lists, Shakespeare quotes, typography that verges on concrete poetry. He bends and mangles these characters in the book to contend that Damien Hirst’s sculpture of a shark in a box of formaldehyde, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, is little more than art-less murder, a burial in mid-air – playboy art; big business. In Day’s view there is more to be learned from making a cat out of the letters M and Q – which he does – with the M marking the ears and the Q sitting just beneath for the body and tail. Day justifies the way a cat kills a mouse to contrast Hirst’s senseless, tasteless killing.

Day’s use of a self-defined ‘analogous’ approach is coupled with personalanecdotes. This gives the book complexity and colour to shake off the laziness that is all too prevalent in contemporary art criticism. Both Day and Davies dance and side-step, placing famous and historical cultural figures alongside Hugo Ball’s Dada poems, Peter Cook jokes, and even betting equations for the Melbourne Cup. It sounds messy, but the connections and slippages of these digressions make for an intoxicating and dissonant piece of prose: ‘Out vile jelly. Art needs to be playful, naughty, confronting, visceral.’

The way these two essays move around and through each other is reminiscent of Correspondence: Jonas Mekas–J.L. Guerín (2011). The pair, each shooting half of the film, exchange filmic letters that reflect on cinema, their methodologies and intentions, and their overall philosophies on life. Like Lost Art, these ‘letters’ alternate between the theoretical and the jovial. One of the scenes is an immensely long take in Mekas’s studio. It is as though Samuel Pepys is behind the camera, meticulous as it rolls. After being led through most of Mekas’s home, we are brought to a modest editing desk where the film-maker cuts his films by hand. Rushes play for some time until our ninety-year-old narrator explains that he is working on what he believes will be his last film. The film is to collect all the out-takes of all the films he has ever made, and is to be simply called Footage.

What lies here is a purity of creative expression, an arrow to pierce the complacency of the art world’s focus on money and professionalism. Mekas and Guerín, Davies and Day make art simply because they must. It is a tenacity that cannot be measured and that should not be forfeited.

The words of Davies and Day play out in the key of an ecstatic truth, at once lilting and rigorous. Lost Art is both welcomingly critical and magnetically alive. I applaud its passion and romance of expression, and as I close its pages I smile at the cat that sits on the back cover, perched at a glass window, looking out to kill.

Comments powered by CComment