- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Long before the era of digital media, the catalogue raisonné evolved as a virtual art museum to house the oeuvre of a single artist. Such scholarly tomes are known by the French adjective meaning a ‘reasoned’ catalogue, implying a tool for making sense. Thus by assembling each work with precise details on medium, dating, and provenance, an artist’s career can be fully understood and any attribution can be tested.

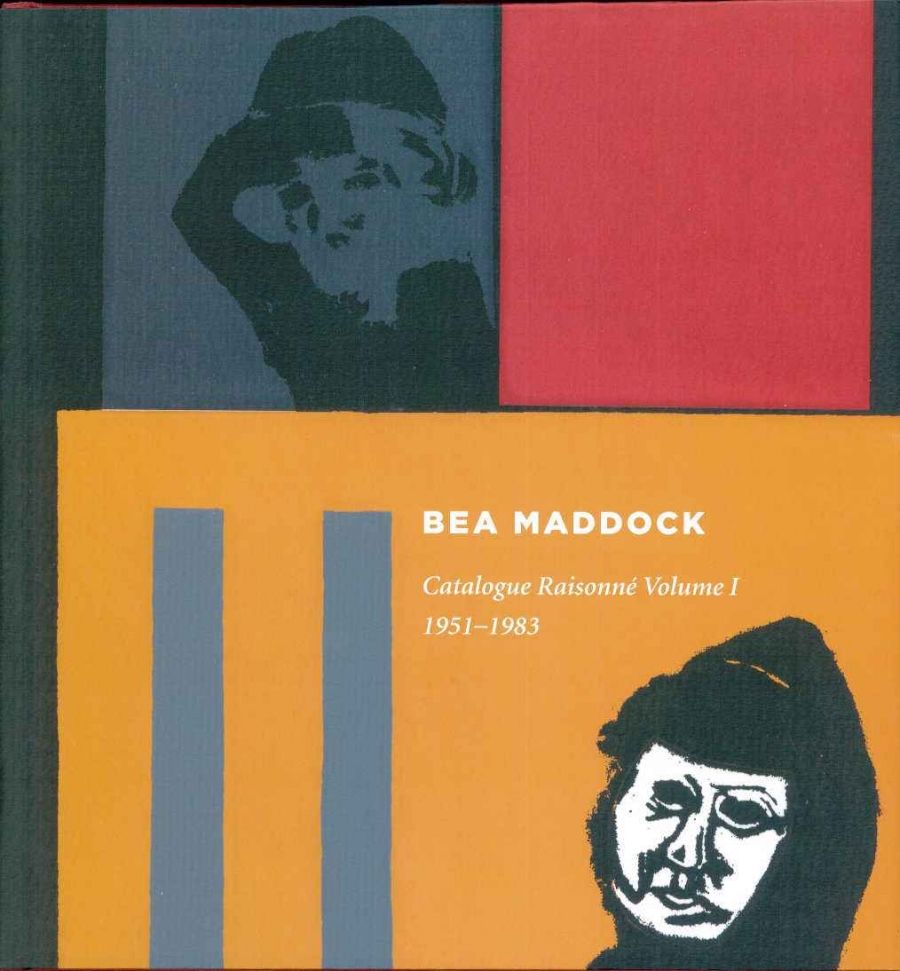

- Book 1 Title: Bea Maddock

- Book 1 Subtitle: Catalogue Raisonné Volume I 1951–1983

- Book 1 Biblio: Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, $99 hb, 302 pp, 9780977595563

The ideal circumstances for a catalogue raisonné are threefold: a major artist willing to commit time to a probing investigator searching for facts; a curator cum art historian with a deep knowledge of the artist’s practice, an eye for meticulous detail and the big picture; and a publisher prepared to support such a massive, long-term project. Famously, Christian Zervos undertook the epic task for Picasso in the early 1930s and, at his death, had completed thirty-three volumes, though the catalogue has since been overtaken by more voluminous scholarship.

In the case of the Australian artist Bea Maddock, the stars have aligned. The eminent curator Daniel Thomas, editor and chief collaborator on the catalogue, outlines Maddock’s extraordinary engagement in the project. Many entries ‘include her comments, helped by extracts from letters written at the time of making … No other Australian artist has been so extensively involved … no other such catalogue has presented so much of the artist’s own thinking about art making.’

Thomas is her perfect interlocutor; their lives have uncanny parallels. They were born only three years apart, at different ends of Tasmania. Both left their island home to study in the United Kingdom in the 1950s: Thomas to Cambridge, Maddock to the Slade. They went on to have outstanding careers in Australia over the following decades. Throughout the 1960s Maddock, with a bipolar relation to her origins, was drawn back and forth between Melbourne and Launceston, finally returning permanently to Launceston in 1983. Thomas remarks that ‘a generalised feeling for turning points and reversals in time and space is present in most of her work’. By the 1990s both were living not far from each other.

With great vision, the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery (QVMAG), Launceston’s regional art museum, harnessed its resources for the project, backed up by its staff, who contributed research, including an outstanding biographical essay by Therese Mulford. While Maddock is by character a loner, throughout her career she has taught, and much of her work is a response to interactions with students and fellow artists. The two major essays – by Thomas and Mulford – are followed by a collaborative entry on materials and techniques and a selection of the artist’s writings, including poems and statement, all beautifully illustrated. The production values are excellent. The rest of the volume is dedicated to the detailed catalogue. My one, possibly unreasonable, complaint is that I wanted all the reproductions in the book, rather than on the accompanying CD.

Volume I lists almost 1000 works and will be a remarkable resource for Australasian art history; it is shot through with all sorts of revelations: for instance, the formative role of religion, which gives all her work a raw intensity, like that other great regional artist, Colin McCahon. Even in the secular 1980s, when undertaking her sole commission for a major work of public art, the mural (1979–80) for the new High Court of Australia, the twelve wax-coated handmade paper panels have the look of ‘Old Testament tablets of the law’ as much as of found newspaper columns.

Another surprise is the recurring role of mirrors in her work, as testified by hundreds of self-portraits, as well as her ambidextrous play with text in printmaking. One of her artist books, Black Bible: Genesis (1983), encapsulates both these concerns, as she explains: ‘The idea was to start at the back of the sketchbook transcribing from the beginning of Genesis with mirror writing ... The two column layout … was based on traditional Bibles, and it suited the horizontal format of the sketchbook.’

Maddock has a brilliant, though at times quite dark, imagination. As Thomas notes in an aside, ‘Black humour was the response when I once asked Maddock for a one-liner to characterise her work.’ He adds elsewhere ‘She is good at doubt.’ As a young artist she was drawn to German Expressionism and later to existential philosophy. Her postgraduate study in London exposed her to cosmopolitan cultures, though it also turned her to reflect more deeply on her own origins.

A definitive move in her work took place some years later in 1968 after returning via Melbourne to Launceston, when hard-edge colour with cool, pop imagery and photography transformed her work. Take the early screen print entitled Personality A.W. (1969): ‘I made a strict grid composition – influenced by Victor Vasarely and Josef Albers and using colour-perception exercises from my Basic Design classes – in order to surround a single photo-based image. The image, of Andy Warhol … Of course I was interested in Warhol’s work (he was a very Sixties personage) but it was chiefly a matter of a good photo-image being available in one of my books.’

While not closely associated with any movement, her self-reflective practice and profound interest in language made her a fellow traveller of conceptual art. Among her finest achievements are the three large word paintings cut from newsagents’ posters, collaged onto canvas, over-painted with grey acrylic, and covered with clear wax. Made into dictionary definitions like those by Mel Ramsden or Joseph Kosuth, hers are strangely moving autobiographical incursions into the terrain of conceptual terror. She writes of Mutable (1978), ‘the last line had to begin with Mutiny, echoing Mutable at the beginning of the first line. I liked these words a lot. They were strong, and Mutable and Mutinous seemed specially applicable to me.’

Mulford notes in her biographical essay how Maddock always turns difficulty into something productive. For instance, when she lost her house, studio, and much of her work in the Ash Wednesday bushfire, ‘rather than being defeated by the disaster she was cleansed and revived by it’. Like a phoenix she rose from the ashes, returning to Tasmania in 1983. Her remarkable new body of work will be the subject of Volume II.

Comments powered by CComment