- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

David McKee Wright is a curious figure in Australian poetry – and in New Zealand poetry, for that matter. As editor of the Bulletin’s Red Page from 1916 to 1926, he was a well-liked and -respected figure in his own time (1869–1928), but he has seriously faded since. He is thinly represented in a number of anthologies, both here and in New Zealand, and was omitted altogether from Robert Gray and Geoffrey Lehmann’s anthology Australian Poetry Since 1788 (2011).

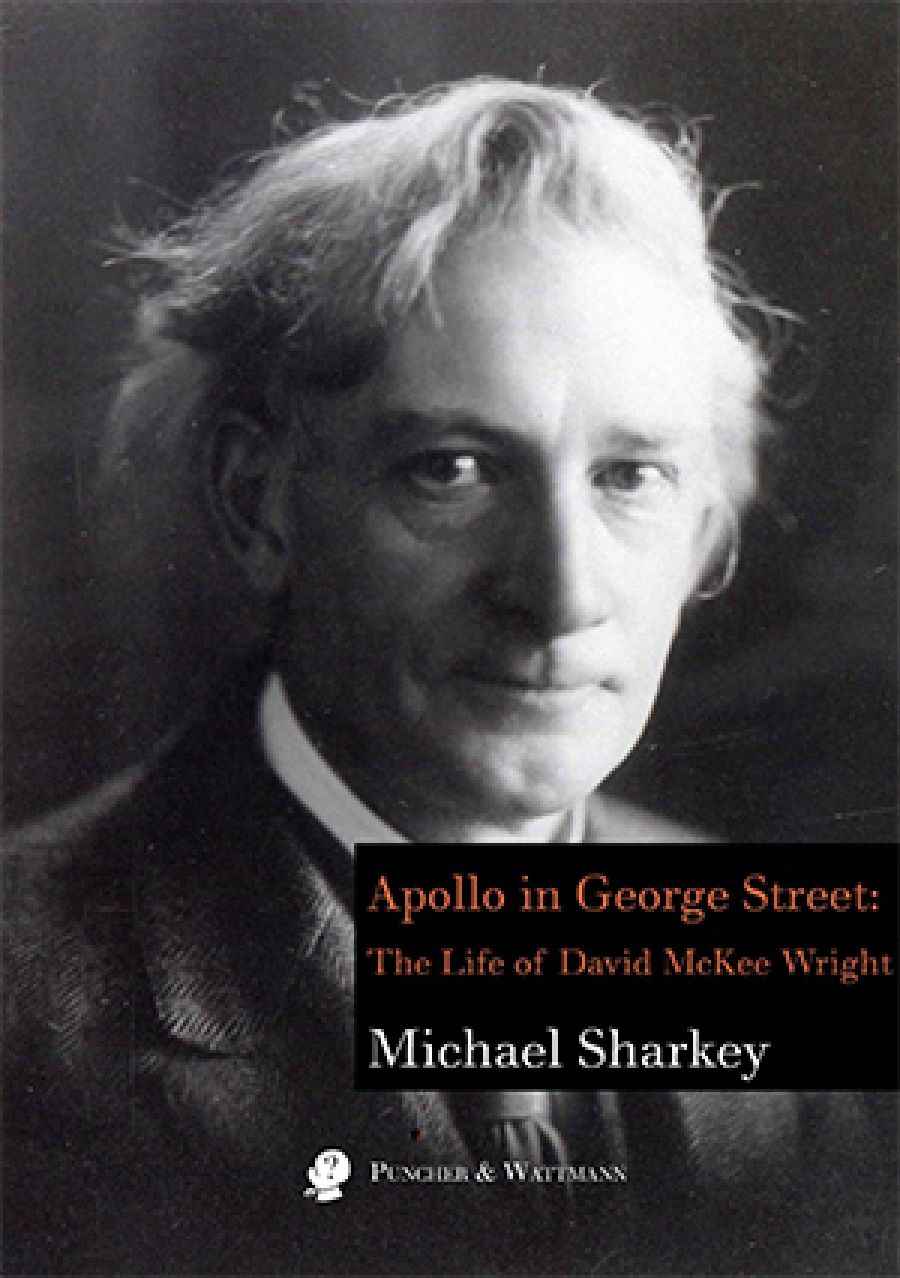

- Book 1 Title: Apollo in George Street

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Life of David McKee Wright

- Book 1 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $34.95 pb, 439 pp

In an appendix to this surely definitive biography, Apollo in George Street, Michael Sharkey traces the dismissal of Wright’s work in the decades after his death and agrees, largely, with the reasons given for it. He does insist, however, that ‘Wright performed a useful role as provocateur in demolishing the vestiges of the bush fixation and dragging Australian literature into the twentieth century’ – even though, paradoxically, he was, as Sharkey points out, a resolute opponent of Modernism.

McKee Wright was born in County Down, Ireland, in 1869 of Presbyterian stock; emigrated to New Zealand in 1887 and thence to Sydney in 1910. He established himself as a Congregational pastor in Oamaru and as a poet with three books to his name before leaving the country (and a wife and son) due to financial difficulties.

Sharkey, with strong New Zealand connections himself, treats this period in detail and gives a vivid impression of the issues with which Wright was involved, including the temperance movement, from which Wright was destined to resile. A similar energy marks Sharkey’s evocation of literary Sydney in the years leading up to World War I. Wright sustained himself (plus two successive de facto wives and a growing number of children) almost entirely from literary journalism, though his position at the Bulletin was important, if not well paid.

To some readers, Sharkey’s biography may prove a revelation. Most will have had no idea how lively was the literary and journalistic scene in pre-World War I Sydney. Each year Wright placed literally scores, sometimes hundreds, of poems in magazines such as the Bulletin, the Triad, the Worker, and others. He also, often under a range of pseudonyms, contributed short fiction, plays, critical essays, paragraphs of literary gossip, and much else. Wright was just one of dozens who worked this way, though probably the most prolific. It was also a time of transition: the bush balladry of the 1890s was more or less over, but Modernism, as represented by Kenneth Slessor, had yet to arrive. Radio and cinema were still to make an impact. Magazines and newspapers (and the books they reviewed) were, along with theatre, the main source of entertainment and intellectual debate.

Without reading Wright’s five (out-of-print) collections, it is hard to assess the quality of the poems. Sharkey’s generous quotation from at least 350 of them does, however, deter one. It is clear that Wright had talent and a definite facility for rhyming and scanning, but almost all of the examples that Sharkey quotes favourably have serious defects that make one wonder just how bad the poems as a whole must have been. Even Wright himself noted, in 1910, that he had written ‘Bad verse, mostly, twisted prose tufted with jingle, echoes of old fragments of rhyme gathered by mistake for poetry in the days of a misguided childhood – never a song with a living note in it.’

An additional problem is the huge number of ‘topicals’ that Wright published under a range of pseudonyms. These poems treat political and social issues, and are generally no better or worse than their numerous competitors. While often defective as poetry, they do enable Sharkey, and us, to traverse the range of Wright’s thought – and some of its contradictions. Not only did the poet shift his ground totally on, for instance, the temperance movement, but he was also simultaneously writing pro and con verses on the 1916 conscription referendum for the Bulletin and the Worker. Wright was very much a writer of his time, swimming easily in its currents and prejudices.

Several of the latter are, of course, unacceptable today – notably Wright’s belief in white supremacy and his disdain for other races. At the time there were few to disagree, but the poems embodying these ideas have not worn well. Paradoxically, however, Wright seems to have been generous to a fault and congenial in company. If the poet was ‘of his time’, then one distinct virtue of Sharkey’s book is that it shows just how complex that time was. One may now shrink from some of the ideas then commonly held, but one cannot deny the liveliness of the participants.

A related virtue of the book is the picture that Sharkey creates of Wright’s successive female companions and the milieux in which they lived. Given their differences of personality, Wright’s 1899 marriage in New Zealand to Elizabeth Couperwas almost certain to fail, despite their producing a son and Wright’s becoming for a time a successful Congregational clergyman whom many admired. His de facto relationship in Sydney with Beatrice Osborn (who wrote under the name ‘Margaret Fane’) was much happier. Together they had four sons, but this relationship too ended when, in 1919, Wright set up house with the poet and novelist Zora Cross, who bore him two more children and stayed with him until his death in 1928.

The conflict between Wright’s last two women – and its partial resolution – is, as detailed by Sharkey, good gossip by any standard. The fact that this all took place at a time when ‘illegitimacy’ was still an issue makes it even more interesting. Certainly, Zora Cross was a forceful lady, and the fact that she loved Wrightand stayed with him to the end is surely to his credit as a man – though not necessarily as a poet. Cross admired Wright’s work as well as the man, but her own poetry has travelled rather better.

The book’s gossip widens to include characters such as Christopher Brennan, a good friend of Wright’s last family and popular with his children. It also includes the writer Hilary Lofting, brother of Hugh Lofting, who wrote the Doctor Dolittlebooks. Hilary moved in with Beatrice soon after Wright left, and Wright more or less maintained Lofting along with Beatrice and the four boys – plus the two more that Lofting and Beatrice had afterwards.

Sustaining such a tribe on a Bulletin wage, with bits and pieces from poetry and literary journalism, was difficult. It is probably the reason why Wright’s poetry rarely rose to the heights he himself would have wanted – and why he died relatively young at fifty-eight. He was, however, a dedicated and talented gardener, as well as a connoisseur of china and a great book collector. If Sharkey refers to Cross’s mother as ‘an athlete of self-pity’, Wright certainly had none of it himself, although he was probably entitled to some.

It is not easy to identify the likely audience for this lively and well-written book. Certainly, scholars of Australian literature will read it, and be relieved to see it thoroughly footnoted. Australian poets may be tempted, but at 439 pages it is not a casual read, and Wright’s fate may seem chastening. Historians wanting more on Australian intellectual trends in the pre- and post-World War I period will also find it absorbing. Whether Wright deserves such extensive treatment is debatable, but I for one am glad that he has received it.

Comments powered by CComment