- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Michael Farrell was the 2012 winner of the Peter Porter Poetry Prize, awarded by this magazine. open sesame is his latest collection of poetry, and an earlier version of it won the inaugural Barrett Reid Award for a radical poetry manuscript, in 2008. It has 123 pages.

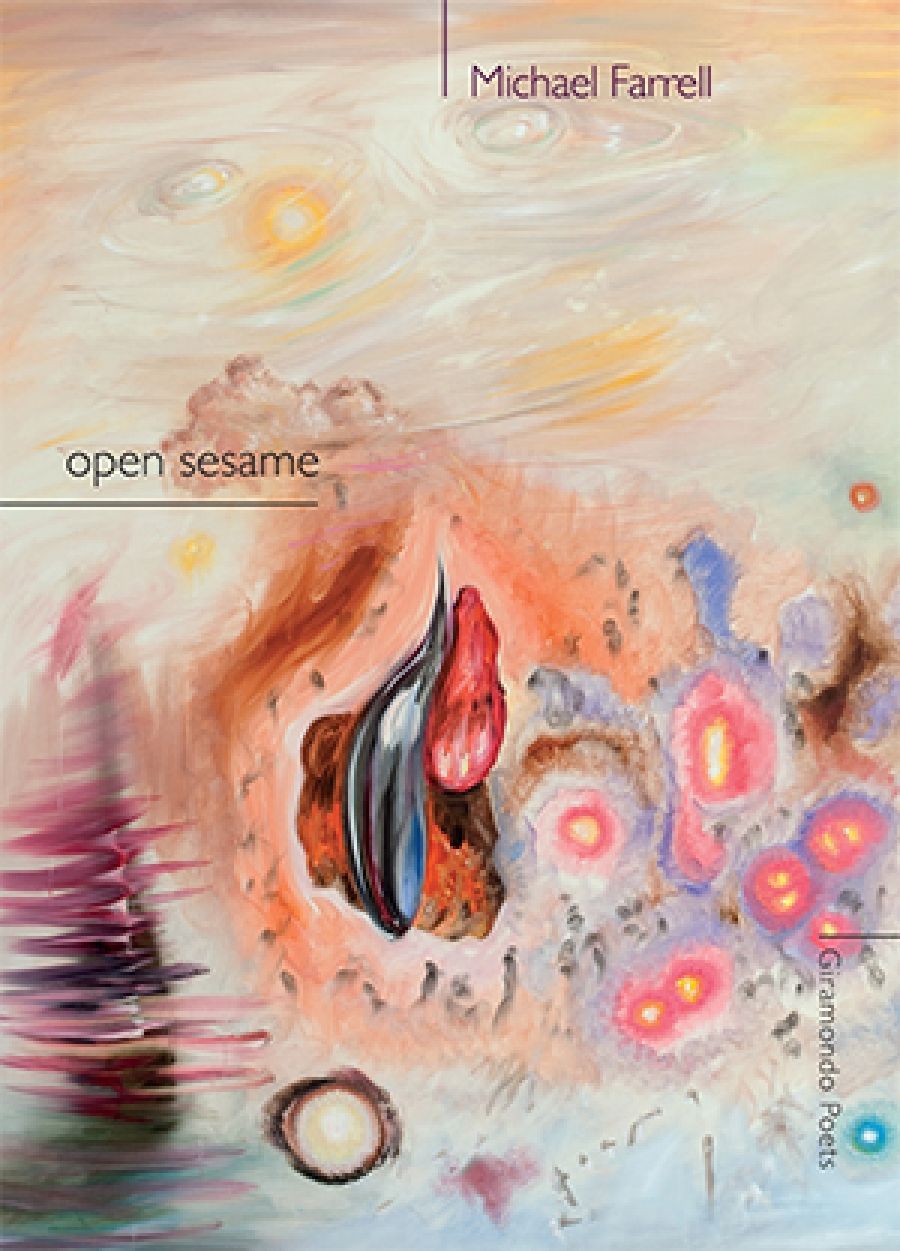

- Book 1 Title: open sesame

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $24 pb, 123 pp, 9781920882846

Those are statements that can be made about this book with certainty. There are not too many others. Farrell, as ever, plays relentlessly with the structure and punctuation of poetry, employing chance and the enabling constraint, sometimes with the numbers showing through the paint, but more often with the paint in unlabelled tins sitting next to the canvases, which have been cut up and reassembled at random.

Much of the pleasure in reading Farrell lies in trying to work out exactly what he is up to at any given moment. In ‘o+n+e’, letters explode like power chords among the lines of what could be the synopsis of one of those sprawling ‘generational’ novels:

a sun on you like

a painter d f h b e & your pet makes

friends with emptiness because its

cool

& when

they got

it home it wasnt an

elixir at all q n g w k o l a wry face.

This is followed immediately by ‘minimalism over two pages’, two pages of text with nearly all the letters plucked out by some ludic text bot – a kind of inversion of Tom Phillips’s text mining in ‘A Humument’, but without the pictures. This sort of thing is not for everyone, and while it can be exhilarating, surprising, or shocking by turns, too much of it at a sitting has an enervating effect.

There is, however, more to open sesame than endless novelty. What Farrell’s poetry demands is not so much that the reader gets it all, but that the reader pays attention. To everything. Punctuation, for instance. Sometimes there isn’t any at all, and sometimes it is all there but there aren’t any capitals, or only a few, and no apostrophes, and the sense is that there is a reason for every variation. At a certain point, which could be anywhere in the book, there is a revelation: it is like the world. We hear, half-hear, and fail to hear an endless stream of words and fragments all the time. Some we hear in ordered packages, and others are inchoate, harsh noises, or faint hints, like someone talking in another room, possibly about us.

Apart from ignoring anything we do not immediately comprehend, all we can do is infer and deduce facts about the world. Reading open sesame requires the same application, and it rewards the effort with varied, ineffable delights and also, to be sure, annoyances.

Delights include six sonnets based on characters from The Bill, conjuring up all the roiling magic at work beneath the streets of Sun Hill: ‘brandon / last night was a spice cigarette / long sweet & heady after a turbulent day, / i dont mean im going to tell you, / cathy to butt out or find another flame, / music has its rise and fall, / the smokiest jazz tends to the impromptu,’ And indeed, like a free-jazz musician casually dropping thirty seconds of ‘My Funny Valentine’ into an evening of atonality, he gives us a sestina (‘What goes around’) that is pure heart-lifting swing: ‘in the magazine paparazzi shots of bad plastic surgery stars / no one like that in the laundry / were all beautiful in the laundry / smiles across our dials white and sweet as marshmallow sandwiches’.

Those stories we hear, half-read books, movies watched while half asleep, people we once knew, or places that speak of youth or passion: Michael Farrell has a strange archetype for them all. ‘the ballad of bubble and squeak’ is a semi-nonsensical skip through an amour fou that is half Belmondo andSeberg, half Sid and Nancy. While the abstract wordplay can sometimes seem arid, there is a real, if slightly ironic, affection in a poem like ‘friends’, which takes a group of young poets and shines them up until they are like the young lawyers in This Life – all sexy, louche, and necessary. In fact it is like an Alan Wearne triple-decker, except that it doesn’t rhyme or glower, and it is only four pages long.

Annoyances include the tendency Farrell has, in common with many academic poets, towards the lame, donnish squib: ‘Substitute’, for example, which reads (in total): ‘You think my shoes are made of / weather’. Cue a pained smile from the assembled undergrads.

The book fades out on a humdrum note with some collage poems, and a concluding one that has two pages of numbers with random words alongside them. All very puzzling. Is it an Oulipo poem? No. Here Farrell has the last laugh: it is the index.

Comments powered by CComment