- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

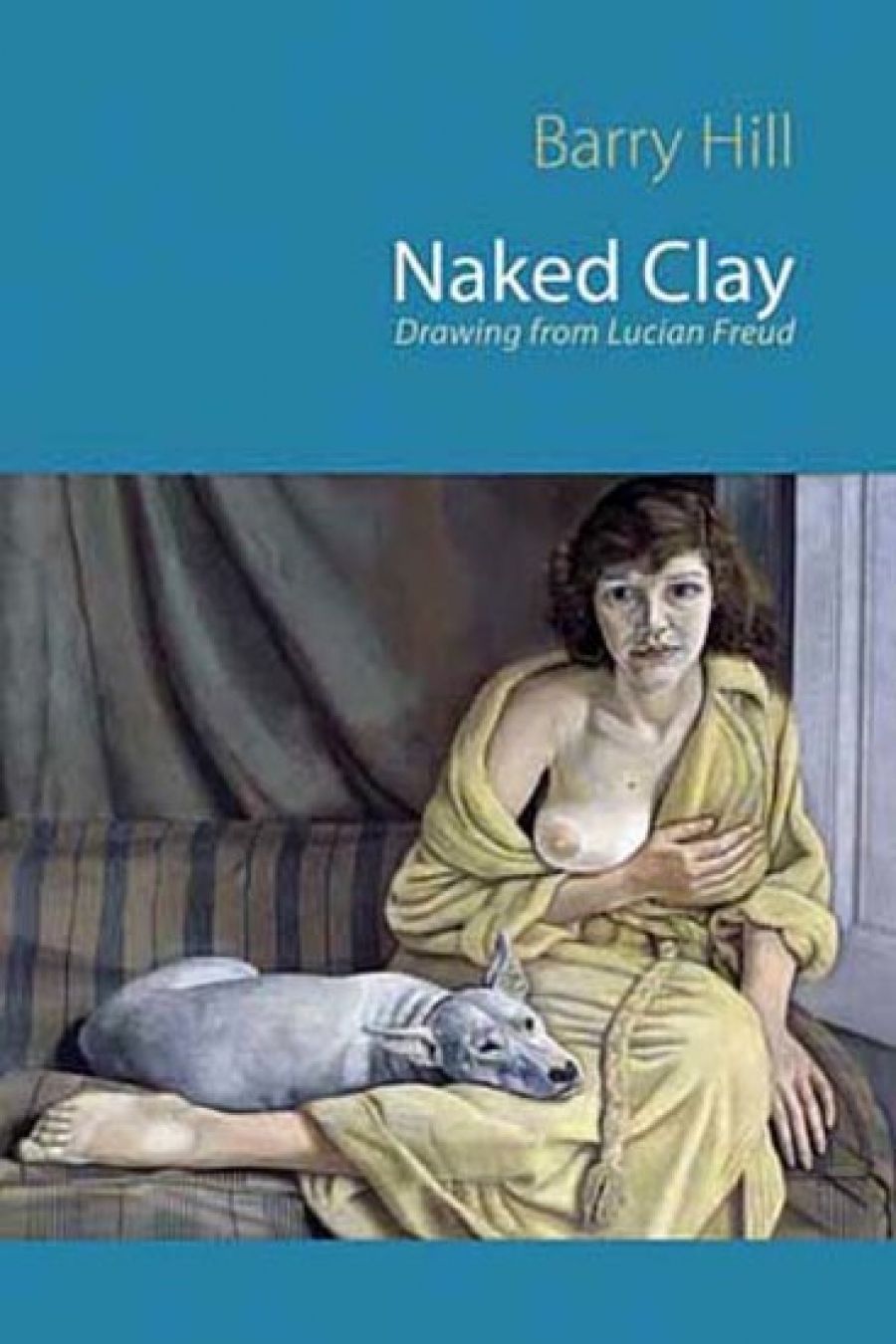

With his new volume of poetry, Barry Hill has set himself the challenge of writing a book focused on the visual art of the recently deceased Lucian Freud without, excepting the cover image, accompanying reproductions of the paintings to which he responds. Naked Clay: Drawing from Lucian Freud is a collection of ekphrastic poems born out of the obsessive return to a body of painting that spanned much of the latter half of the twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty-first.

- Book 1 Title: Naked Clay

- Book 1 Subtitle: Drawing from Lucian Freud

- Book 1 Biblio: Shearsman Books, $25 pb, 160 pp, 9781848611780

As a figurative painter, Freud made the human his subject, and is particularly known for the nudes he rendered replete with their bodily flaws. The human subject is both narrow and endless, and just as the viewer is struck by repeated gestures made by the artist when viewing Freud’s paintings in succession, so too is Hill’s poetry here marked by its subject of a single artist’s oeuvre.

In many poems, Hill stays within the frame of the image he is describing; he does, however, depart from the paintings themselves frequently throughout the collection, allowing the reader to sense the speaker of the poems as a consciousness affected by the works of art. The poet’s subjective response invites the reader to experience it, too – as in ‘Mother: Portraits’, when Hill writes, ‘You can feel her settling, uninquiring / listening to the brush patterning her in, in’. This poem, looking collectively at portraits of Freud’s mother painted over the course of years, stands out for its concentrated meditation on mortality and the relationship between mother and son.

Elsewhere, Hill’s response is driven by his own inability to look away, as in ‘Getting to Grips with Naked’ when he asks

How do they bear it

endure such brutal looking?

All the while knowing

even settling into weary

sleep is no shelter from his slow turning

of their bodies on the wheel

his handling of their clay?

The brutal gaze of the painter becomes first the brutal gaze of the viewer and then of the reader; the brutality of seeing and being seen is one of the primary interests of the collection.

In the book’s third section, ‘In Sight of Death’, comprised of a long poem of the same title, the poet explores his relationship with the paintings he describes throughout the collection, again in a personal way. The poem begins with the words ‘My body, its secret insides I hardly know …’ and the unknown insides of the speaker’s body are contrasted with the subjects he witnesses, whose bodies ‘are like horses in stables’. He later describes these subjects to himself as ‘the strangers you’ve come to love’.

Just as Freud’s paintings are unflinching in their portrayal of the human body, Hill likewise looks intently at the body. His rendering of Freud’s vision into words is confronting and often visceral. While he does at times fall back on familiar descriptions of colour – ‘pale as milk’, ‘pearly white’ – often his descriptions are animalistic: we see ‘lips the plummy mauve of a dog’s balls’; we are asked to imagine ‘a soft monkey-bum pink’. Although these descriptions can be startling, the cumulative effect is lessened when once again the body is shown as animal.

Moving past the mere evocation of colour, Hill brings the other senses into play. In ‘Lying by the Rags, 1989–90’, he writes of the woman depicted ‘Her underarms sour, the pelvic stubble / bristly as a lavatory brush.’ Hill repeatedly confronts the reader with the fact of the body, imagining the scene fully beyond the texture of the painted surface. While repetition allows the reader to discover or rediscover Lucian Freud’s obsessions through this textual exploration, as poems return to these naked bodies, the sense of discovery wanes.

Nonetheless, over the course of a large collection, Hill retains the reader’s interest, and it is the infusion of playfulness and occasional song-like moments that sustains the volume.

By stepping beyond the frame of the painting and into an imaginative zone, the poet renews the painting itself. In ‘Wasteground with Houses, Paddington, 1970–72’ Hill creates a long catalogue of the scene of a father’s death: the act of listing ordinary objects and settings becomes a moving exercise, and, just as the painter has transformed the scene, so too does the poet achieve an incantatory style when he looks

at the top of the thick brick fence below

at the rooftops in the near distance

the slate, the chimneys and flues

at the backs of flats mostly with windows closed

at the end of a single-storey run

of stables or mews studios facing the

lane

In Naked Clay’s final long poem, ‘Magnanimity’, Hill addresses the reader directly: ‘You to whom I have been speaking of these bodies / painted and unpainted, drawn and hung …’ The public and private moments hinted at by this gesture towards what has been put on the canvas and what has not, alongside the language common to both art and the executioner’s block, draws together the concerns of this collection.

Comments powered by CComment