- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What makes a good architectural photograph? In an ideal world, it is the product of a dialogue between the architect’s intentions for his or her building; the built form and its synergy with its environment; and the photographer’s ability to interpret these elements in a creative and dynamic way. A successful photograph should offer a clear visual representation of a building, but it should also capture its defining spirit. And there is one final element which often remains an unspoken, if fundamental, part of this process: the role of photography in ‘selling’ a building. So it is interesting that this large book celebrating the work of John Gollings begins with a quote by the great American architectural photographer Julius Shulman, which states, in part, ‘the truth is that I am a merchandiser. I sell architecture better and more directly and more vividly than the architect does.’

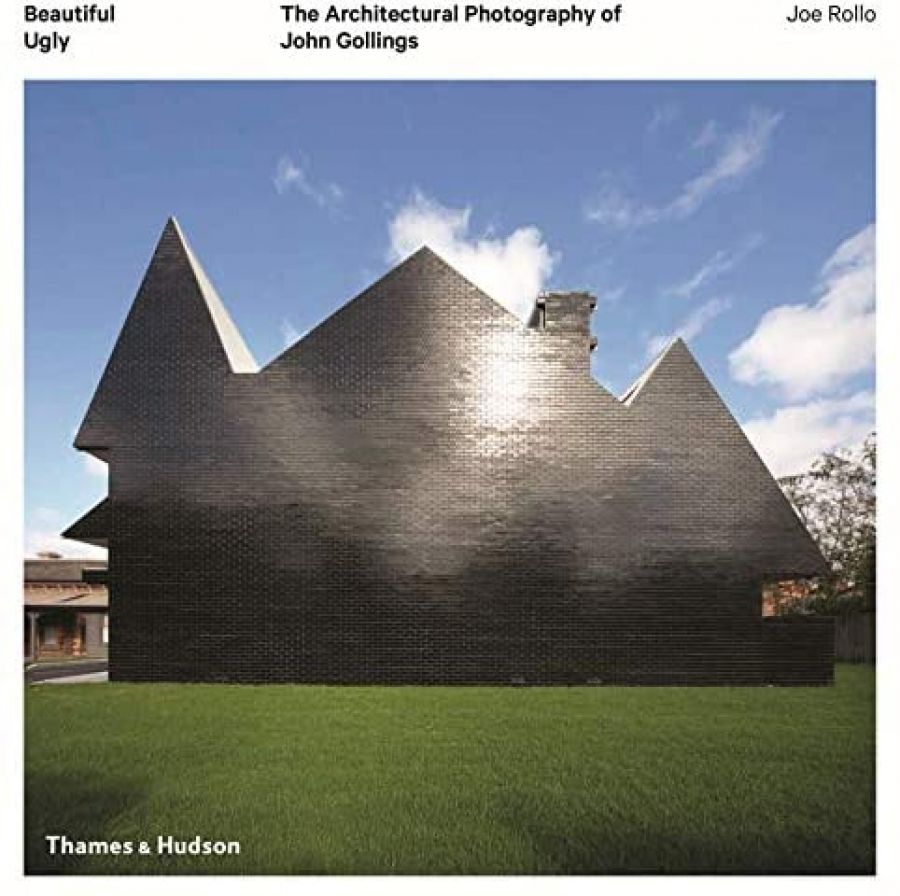

- Book 1 Title: Beautiful Ugly

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Architectural Photography of John Gollings

- Book 1 Biblio: Thames & Hudson, $120 hb, 332 pp

The quote seems to answer those critics of Gollings who, over the years, have accused him of overly ‘flattering’ buildings: a claim that seems to have left him unfazed. Gollings has no problem, as he writes, with turning modest architecture into a heroic structure; he believes that it is simply his ‘take on it’. He also maintains that ‘The camera can’t make a bad building look good, but you can’t define architecture without good photography.’

There is, as Gollings suggests, a long-standing symbiotic relationship between architecture and photography. Most people have limited access to private homes or architecture in remote locations, and this means that the only opportunity to see these buildings is through photographs. Over time, too, many structures are destroyed or altered, leaving photographs as the only lasting record of their original appearance. Even with those buildings that are accessible, their complexity or scale may mean that only a photographer can capture their totality or suggest how it is that the architect wished them to be viewed. In short, as Gollings observes, a good photograph may be better than actuality.

The chief purpose of this book is to highlight some of Gollings’s key projects over his forty-year career to date. It includes a generous number of full-plate illustrations of both Australian and international commissions selected by the photographer from the eight million images in his archive. The emphasis is on the visual, but the addition of short captions, technical information, and several feature stories throughout the book offer a good insight into how he works and his philosophy of photography. What emerges is a distinctive ‘Gollings style’: dynamic, inventive, heroic. He frequently takes aerial photographs; often works at dusk or night; is known to adopt exaggerated perspectives for added drama; and uses flash, double exposures, and floodlights. In one recent act of creative bravado, Gollings worked at night flying in helicopters at 610 metres (leaning out of an open door in harness) to take two images precisely twenty metres apart that were then merged in the studio to produce three-dimensional photographs. Gollings – and his team of assistants and post-production staff – were among the first in Australia to maximise the pictorial possibilities of the new digital processes, and it has undoubtedly given a sophisticated edge to his work.

Given his passionate embrace of new technologies, it was interesting to read in Joe Rollo’s short overview of his career that Gollings cites Charles Meere’s painting Australian beach pattern (1940) as an ongoing inspiration. It seems that this iconic tableau helped give him the confidence to create his own narratives. One could also conjecture that Meere’s muscular celebration of beach life spoke to Gollings about the creation of a heroic Australian identity; a quality with which his work often engages.

Gollings was fortunate that his energetic, highly orchestrated, and often narrative photographic style coincided with a new moment in Australian architecture, which appreciated his fresh approach. In the mid-1970s a new generation of progressive architects no longer wanted the ordered modernist images with which outstanding photographers such as Mark Strizic, Max Dupain, and Wolfgang Sievers had supplied them, and turned to new artists, most notably Gollings, who was eager to break established pictorial rules for the sake of impact. Gollings forged enduring relationships with Australian architects Peter Corrigan, Philip Cox, Nonda Katsalidis, and Denton Corker Marshall, among many others, and several contribute revealing vignettes to this book about how Gollings approached photographing their buildings.

Gollings may state that ‘Buildings control the photography’, but the evidence of this book is that the relationship is not one-way. Gollings has worked tirelessly to bring Australian contemporary architecture, in particular, into public consciousness. Many of his iconic photographs now define how we have come to view certain buildings and, on occasion, have helped to shape our view of modern Australia. This book, the most substantial overview of his career, does great credit in showing how John Gollings’s considerable talents have brought to life the essence of contemporary architecture.

Comments powered by CComment