- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Throw the name Lucio Fontana into any dinner table discussion about twentieth-century art, and chances are the first comment thrown back will be, ‘He’s the Italian guy who slashed his canvases.’ He certainly was. But there is much more to him than that, as this exquisitely produced and exhaustively researched book by Anthony White shows.

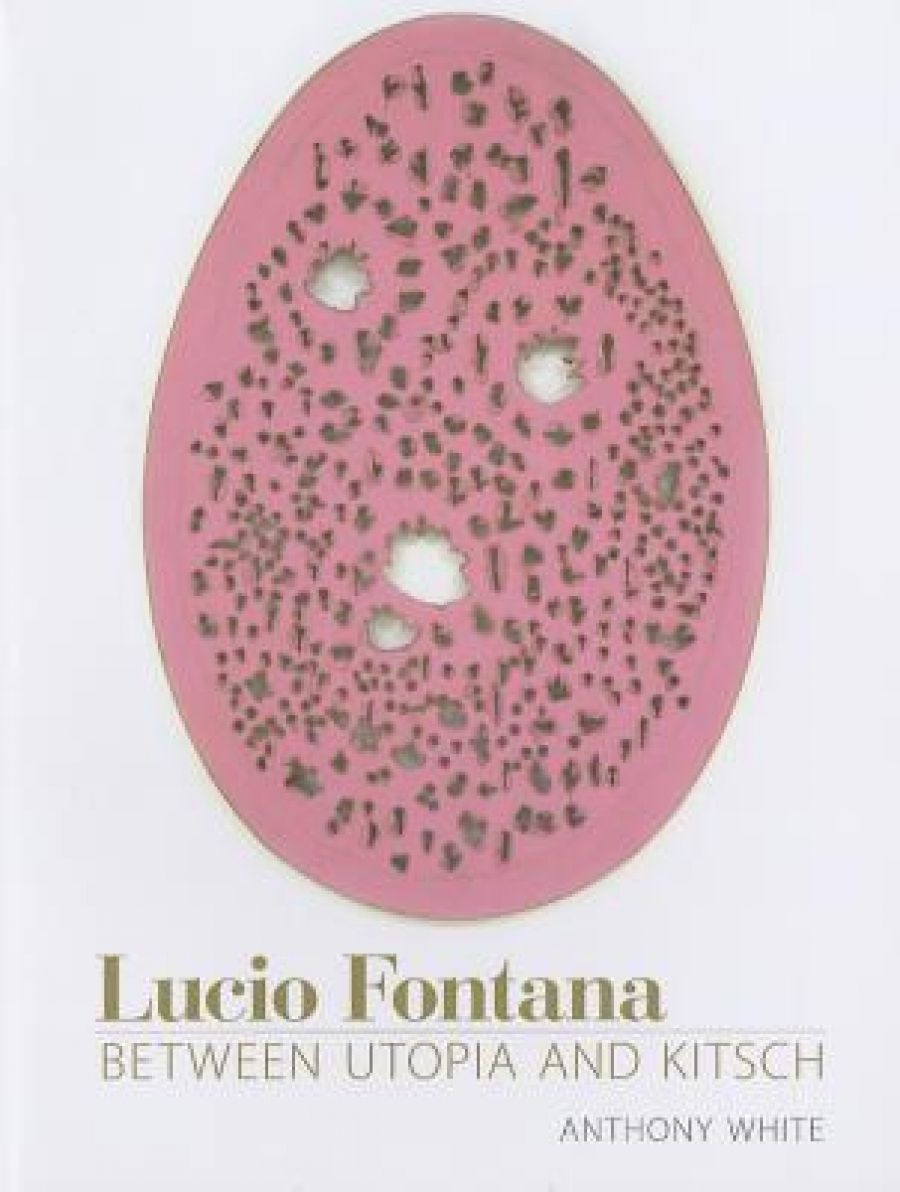

- Book 1 Title: Lucio Fontana

- Book 1 Subtitle: Between Utopia and Kitsch

- Book 1 Biblio: MIT Press (Footprint Books), $29.95 hb, 338 pp

Much of it was new to me. A more informed dinner guestwould likely interject that Fontana was actually born in Argentina, to Italian parents. His father was a commercial sculptor who specialised in works for civic squares and graveyards. He was successful in his business, but not so much in his marriage. When he and his wife separated, Fontana’s father took his young son back to Italy. Lucio attended many schools, including one for master masons, and later his father’s alma mater, the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera.

White tells us, ‘Fontana’s artistic education was interrupted by World War I; he enlisted to fight on the eastern front. As he later recalled, “I was seventeen years old. I enrolled, as a volunteer, in the Italian army. I saw and lived all the horror of the battlefield for two years.” Although he was awarded a medal for bravery, Fontana also suffered a severe case of frostbite to the arm and was consequently relieved of combat duties.’ By 1920, a grinning photograph shows him ‘proudly sporting the black shirt and fascist emblem badge. Nevertheless, the experience of war weighed heavily upon Fontana and left him with “a bitter taste of tragedy and the pressing desire to return to my native country, tormented and deceived”.’ By 1922 he was back in Argentina, making figurative sculptures, and setting up his own studio and workshop.

Over the past one hundred years a number of significant artists have combined creativity with acts of destruction. Joan Miró, as last year’s huge show at Tate Modern revealed, partially burnt many of his large canvases in a passionate anti-fascist statement. These were hung sympathetically from the ceiling in such a way that they could be viewed, through the holes, from both sides. Jean Tinguely specialised in self-destructing sculptures, while Yves Klein also used fire as a creative-destructive element in his work. Both can be seen on YouTube collaborating on some of these historic performances. More recently, in London, Michael Landy, in his work Breakdown (2001), destroyed all of his possessions – passport, car, clothing, CDs, and, controversially, the work of other artists, which he had bought or been given – in a vacant Oxford Street store equipped with a conveyor belt and manned by numerous assistants dressed in blue overalls. Everything was eventually reduced to landfill.

Lucio Fontana – the guy who slashed his canvases – arrived at this position via the 1958 Venice Biennale, where he was given, at short notice, a solo retrospective of his work. He hadn’t yet taken a knife to canvas, and wouldn’t do so until after the event. However, he had been building up to it in works where small, circular holes puncture the canvas surface in a way that White describes as ‘machine-gunning’. When the slashes, or ‘Cuts’, as Fontana referred to them, began in earnest between 1958 and 1966, the term ‘guillotine’ would be used in an equally precise way. But let us return to the Venice Biennale of 1958. ‘On the eve of the exhibition opening,’ the author tells us, ‘the artist wrote to a former pupil expressing concern about how his work would be received: “It’s a shame that they only sent me the invitation two months ago, and that for such an important exhibition the time has been very brief, however between the old works and the new ones I hope I won’t cut a really bad figure.”’

Given a space large enough to hang forty works, he delivered in the short time frame available. However, the critics said his work, which he referred to as ‘spatial concepts’, was ‘too elegant and refined’. Some said it didn’t live up to the revolutionary days of the Dada movement. It might be enough to cause any self-respecting artist, caught in the publicity lights of the Grand Canal, to take a knife to his canvases. And that is what he did.

White writes, ‘By the end of the year, Fontana had come up with a startling new solution: the cut canvas. The first public appearance of these works was on the cover of La Biennale, a periodical published by the Venice Biennale, where Fontana threw down the gauntlet to the lukewarm reception given him earlier that year at Venice.’

This scarified cover, reproduced on page 210 of the book, is probably the best evidence we have of how Fontana’s – what I would call ‘minimal expressionism’ – unfolded. There is also a tantalisingly verbal account of his state of mind at that time. It comes from Jan van der Marck, who claimed that in a conversation the artist stated how he had become ‘irritated by his own indulgence in surface embellishment. In frustration he slashed into an unsuccessful canvas and suddenly realised the potential of that gesture.’

Throughout his life, Fontana moved back and forth between Argentina and Italy. He worked with different avant-garde groups in both countries and was part of a larger, international movement. In 1961 he had a solo exhibition in New York, where he showed ten slashed and punctured canvases, which didn’t please the local critics but cemented his reputation. By this point he was using chunks of broken glass set into the picture plane. This is ‘halfway between constructivism and costume jewellery’, one of the Manhattan scribes responded.

I love his work, as I love this book. Back in the 1980s I coined the term (out of frustration) ‘Minimal Baroque’ to describe the work of a young Dutch artist Harald Vlugt. He projected a street plan of Paris onto a linoleum-covered armature that looked like the wing of a stealth bomber. He then gouged out the streets and filled them with red candle wax. Several years later I saw the work of Australian artist Paul Zika, who was experimenting with the ‘Franconium Baroque’ in his exquisitely fashioned three-dimensional paintings. If anyone has a vacant gallery or museum space, I would be honoured to bring all three artists together.

Comments powered by CComment