- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

How can Australians write fiction about Indigenous Australia? It is one of the most contentious literary questions today. There aren’t any rules, but writers – particularly white writers – are driven by a strange mix of passion and caution.

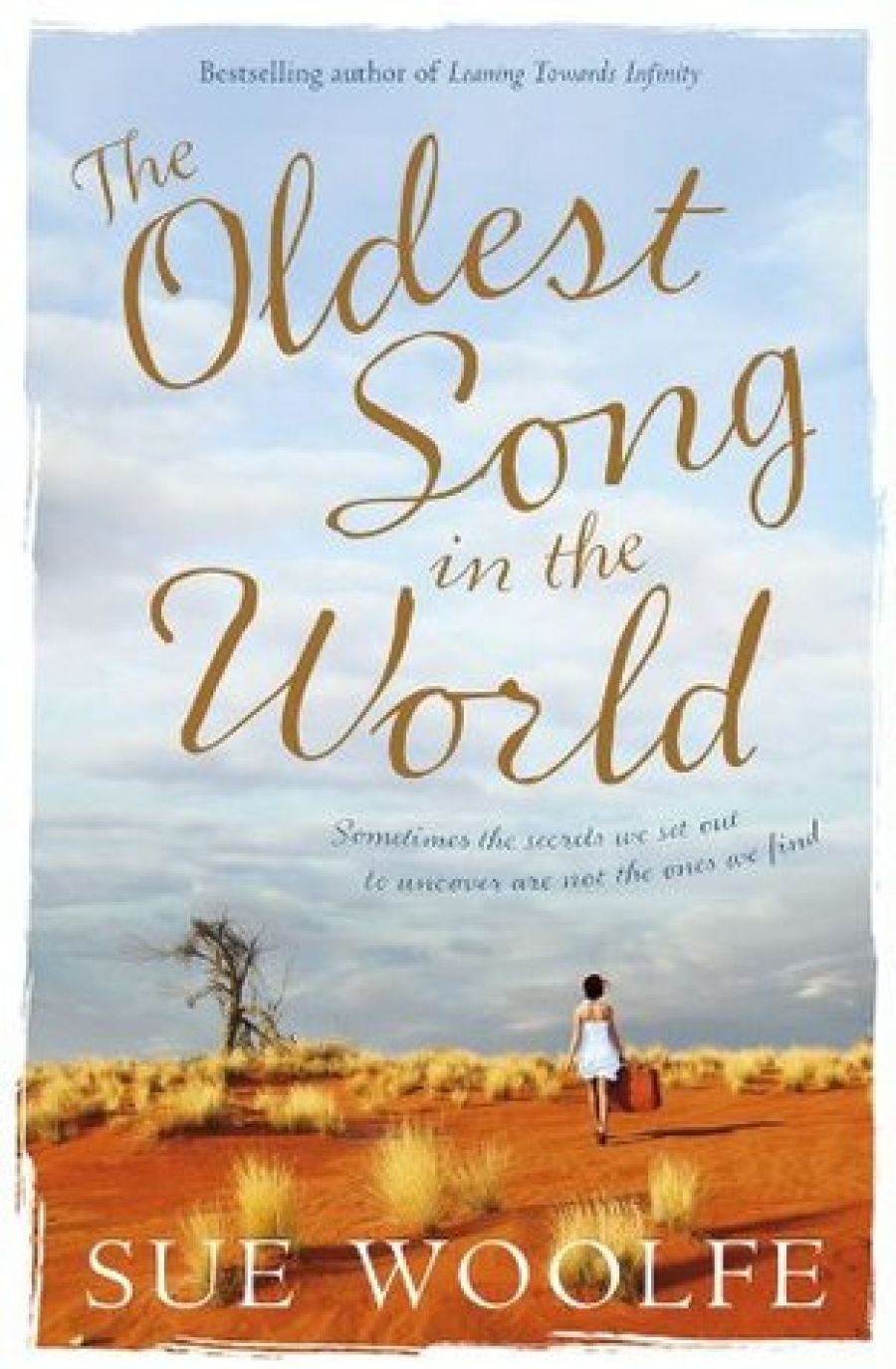

- Book 1 Title: THE OLDEST SONG IN THE WORLD

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $29.99 pb, 393 pp, 9780732294991

You can write from the inside, of course. Writers who draw on their heritage, their special knowledge and kinship, their empathy and imagination, can produce stellar Miles Franklin-winning books, as we have seen in the work of Kim Scott and Alexis Wright. You can also write from the outside and achieve spectacular results. But the consensus seems to be that there is a limit to how far you can go. White writers who wouldn’t hesitate to get inside the mind of a nineteenth-century colonist or a child or a serial killer draw the line at entering the thoughts and feelings of an Aborigine. Kate Grenville has said that she would never try it, and Thomas Keneally has said that he would never attempt a book like The Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith in today’s climate.

Sue Woolfe is no stranger to entering different minds, such as the mathematical genius in her splendid novel Leaning Towards Infinity (1996).But in The Oldest Song in the World she deliberately stands back. For most of the novel we are in a remote Aboriginal community, but we see it through white eyes. And her theme is how farcically distorted that vision can get.

Woolfe’s narrator, Kate, isn’t interested in Indigenous culture. She is studying linguistics because she wants her charismatic tutor to notice her, but she is not a good student. Now in her mid-thirties, she has drifted through life, through brief relationships. All she wants, it seems, is to be noticed. When the tutor offers her a chance to go to a desert settlement and record an old woman’s song in the Djerimanga language – a song that may date back to the Dreamtime – she takes it, but again, her motivation is all about Kate. Adrian, the boss at the clinic who sent the invitation, is someone she thinks she knows from long ago: a boy with silver eyes. They grew up together, they share the heritage of a mysterious family tragedy. His memory has haunted her whole life and she can’t resist the call, described with ironic Hollywood flourish: ‘Then a banner floated across the screen. There was a single word on it: Destiny.’

From the moment Kate arrives in Alice Springs, the misperceptions begin. ‘Welcome to my land,’ says a smiling black woman. City girl Kate assumes the woman is talking about land she owns. On the long, bone-shaking journey to the settlement in Adrian’s troopie, Kate’s gaffes continue. You wonder how she is ever going to talk to anybody, let alone record a secret song.

Well, this is just the failing of a naïve, self-centred young woman who has never been near ‘real-life Aboriginal people’ before, the reader may think. Surely Adrian and the other whites at the settlement will have the experience and knowledge to put her straight, right down to the etiquette of when to look someone in the eye. Surely she will get her song, and maybe a nice romantic moment of epiphany to go with it. But Woolfe doesn’t let us off the hook. Gradually we realise that it is not just Kate. None of the whites – from know-all Adrian to the teachers at the school, the doctors and nurses, the builder, the administrator – has a clue about ‘the mob’. In this sense, the settlement may act as a microcosm of white responses to Indigenous dispossession. They have taken away the land, and in return they ‘hold’ the people. They think they understand, and some mean well and try hard. Others are impatient, controlling, and punitive. But whatever approaches they make, they fall woefully short.

In the details of day-to-day confrontation, Woolfe uses vivid comedy and drama to show up the gaps in commun-ication. There is a cringingly funny visit from a politician who tries to charm the local grandmothers with sentimental stories of his own childhood. In a horrifying incident, one of the elders runs amok with a nulla nulla, but no white has the faintest idea what has sparked off his rage.

Woolfe is adept at portraying the extraordinary seduction of the desert landscape and its treacherous charm: the changing colours of a pink river of sand, the spinifex that spears you when you touch it, the disorienting blackness of night. She is terrific at showing us animals: the donkey and the feral dogs that hang around the dusty streets. The mob remains largely shadowy creatures, but that illustrates Woolfe’s point: if you’re white, you can’t ever assume you know them and their ways. She is less convincing in her depiction of the evolving relationship between Kate and Adrian. Kate remains besotted by her memories, but the reader becomes impatient waiting for the scales to fall from her eyes. Adrian is simply awful. We are led to believe that he is mesmerising, but we see mostly bad, arrogant behaviour.

Woolfe’s refusal to romanticise her subject falters a little towards the end, when Kate strays dangerously close to a nice tidy epiphany. But there is still a moving finale to a captivating and challenging story, and the reader is left with a sense that reconciliation is possible. Kate is shifting from someone who wants to be noticed to someone who is at last noticing herself and others.

Comments powered by CComment