- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Do you remember them on the television news? Stumbling down gangplanks onto our shores, with flickering cubes of light instead of heads. Wearing strange clothes and eating stranger food. They harboured terror and disease. They were said to sacrifice their children. How did it come to this?

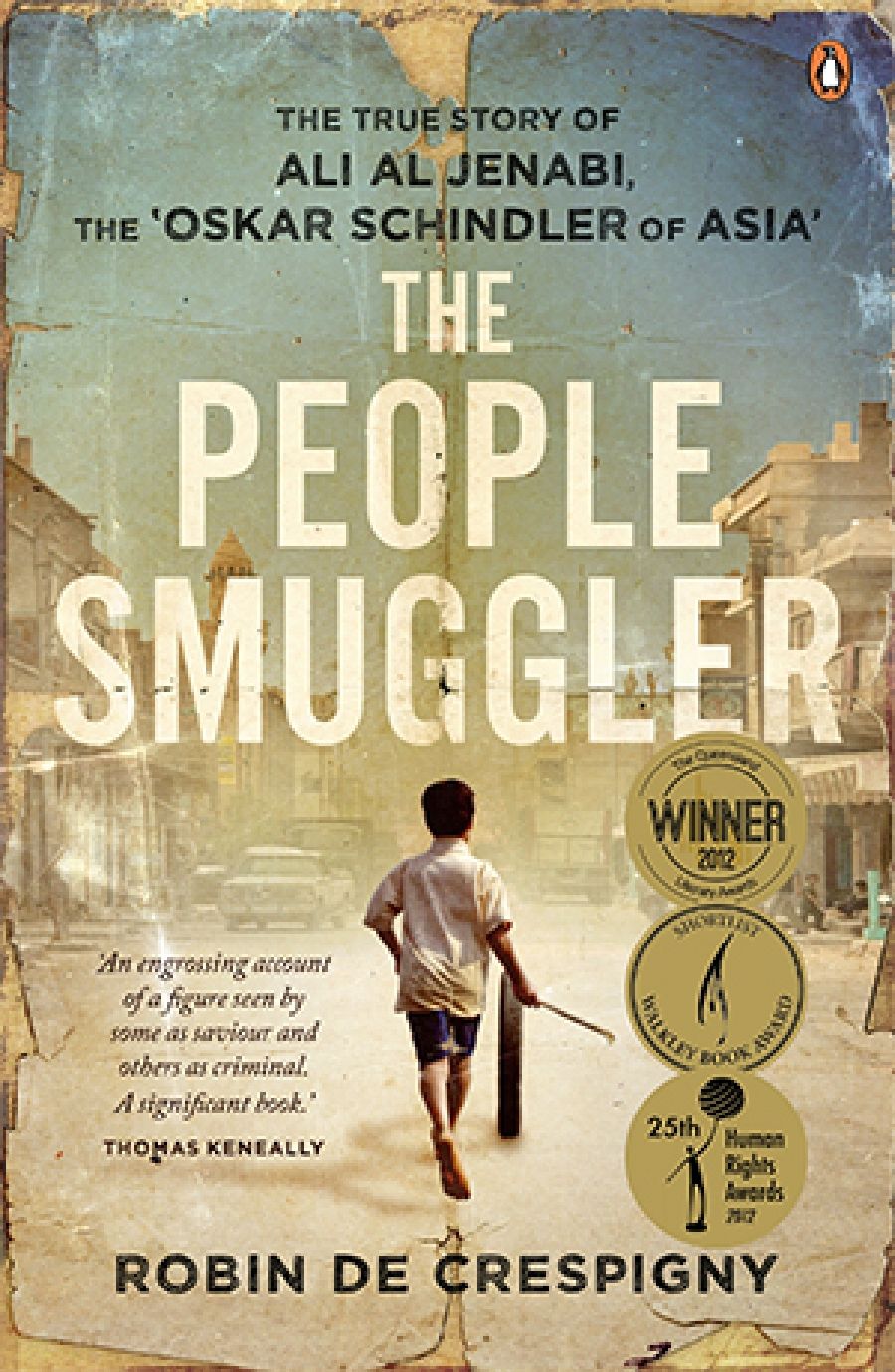

- Book 1 Title: The People Smuggler

- Book 1 Subtitle: The True Story of Ali al Jenabi, the ‘Oskar Schindler of Asia’

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $29.95 pb, 360 pp

Discussion of immigration is rarely rational – often a shadow theatre to play out other social and psychological anxieties. Under the Howard government, asylum seekers became the immigrants you had permission to hate. The pixilation of asylum seekers’ faces dehumanised them: instead of distressed individuals, they were demonised as an anonymous horde.

This chimera of invading masses of ‘boat people’ became a political ‘issue’ and – in defiance of reason – has firmly remained one. When SIEV 221 crashed onto the rocks at Christmas Island in 2010 with the loss of many lives, it became tasteless even for politicians to denigrate them. And so a new demon was cast: the people smuggler. Kevin Rudd’s judgement was typically intemperate, describing them as the ‘absolute scum of the earth […] the vilest form of human life’ who should ‘rot in hell’.

Robin de Crespigny’s account of Ali al Jenabi’s life, The People Smuggler, is an attempt to exorcise this new demonology. It works by telling an individual’s story, questioning the concept of the evil people smuggler as a simplistic, political construction. The cover describes the book as ‘a non-fiction thriller and a moral maze’. It lives up to this promise. While Robin de Crespigny is credited as author, the narrative is written in the first person as though by Ali al Jenabi, based on interviews with him. On the whole this ventriloquism works: the story is as gripping as it is chilling. Ali grew up in Iraq with no political affiliation apart from life membership of the Awkward Squad, but at twenty was taken to Abu Ghraib prison by Saddam Hussein’s police. He was forced to watch as his brother’s hands were nailed to a table before his fingers were hacked off. Ali spent four years locked in a crowded cell, only taken out to be tortured. It is astonishing that he survived with his sanity intact, or survived at all.

After release, Ali joined the under-ground opposition, managing hair’s breadth escapes with the brio of a John Buchan hero. He soon realised that the rebel groups spent as much time plotting against each other as against Saddam, and that their main interest was in the CIA funding they received. Ali’s focus, meanwhile, was on helping his family to escape from Iraq. He was a born fixer. Everywhere he went he set himself up in business, as a tailor, builder, currency speculator, or whatever was to hand. Reaching Indonesia, he decided that helping refugees get to Australia was the best way to finance his own family’s escape. We get an insider’s view of the amateurish, corrupt, and sometimes fatal smuggling of human cargo. The reader is left in no doubt how desperate refugees must be to place their lives in the hands of these clowns and villains.

Ali was betrayed. Flown to Darwin, he became the first people smuggler to be tried in Australia. After years in prison and the Villawood Detention Centre, he was grudgingly granted a bridging visa – the situation he is in today. Against all odds, though, Ali’s work was done: his family was there to welcome him, all Australian residents.

One of the book’s heroes is the judge who presided over Ali’s trial. Justice Dean Mildren was unimpressed with political pressure to make an example of Ali. When the Commonwealth protested that he aided ‘queue jumpers’, Mildren requested proof from Canberra. It never appeared. In the summing up, he compared Ali with Oskar Schindler: not because either was a saint, but because both had mixed motives for their actions :self-interest as well as wanting to help others.

This avoidance of hagiography is one of The People Smuggler’s strengths. Ali was genuinely motivated to help others. At the same time, he was no innocent. His price for a seat on a boat was up to $3000. He confiscated passports so they could be sold on the black market. He displayed repeated willingness to threaten violence against others. Ali al Jenabi is a complex, resourceful, and sometimes ruthless man. He is, in fact, just the sort of person I would want around if my own family were under threat.

The People Smuggler is a gripping and thought-provoking read. It also contributes to unease about the effectiveness of the Refugee Convention, and about the conceptual validity of universal human rights in general. When these were first formulated in the eighteenth century, Jeremy Bentham and Edmund Burke were both immediately sceptical (Bentham called them ‘nonsense on stilts’). More recently, Hannah Arendt and Slavoj Žižek have argued that they are incompetent instruments to help those they claim to protect, that they are a pompous and cruel hoax. The philosophical basis of ‘natural rights’ can also be questioned as an attempt to perpetuate religious perfectionism after the Enlightenment – fundamentally irrational and undemocratic in the insistence on absolute, abstract, and arbitrary ‘natural rights’. Philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre boldly states thatthere are ‘no such rights, and belief in them is one with belief in witches and in unicorns’.

Whether demonised, or patronised as victims of human rights abuse, asylum seekers such as Ali al Jenabi and his family are not well served by either facile generalisation. They deserve better.

Comments powered by CComment