- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

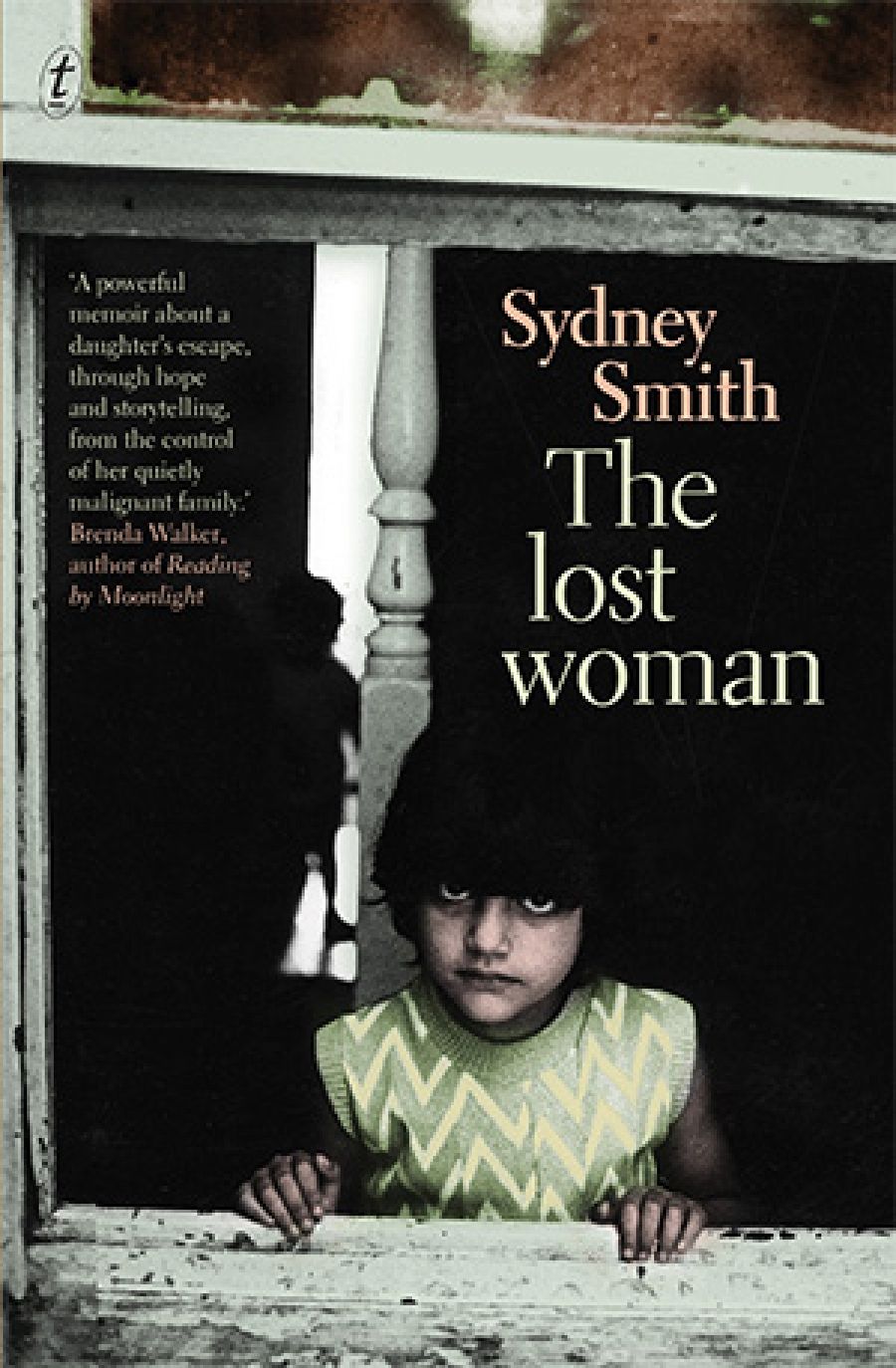

In 1978 Christina Crawford published her memoir Mommie Dearest, an account of her life as the abused adoptive child of Joan Crawford. Shocking scenes in this book remain forever with readers. Sydney Smith’s account of life with her mother is, if anything, more horrific than Mommie Dearest. Traditional fairy tales often split the mother into the good mother and the bad mother, and the one in The Lost Woman is a baroque version of the bad. The memoir begins by invoking the story of Rapunzel and continues throughout the narrative to identify life’s key elements with the tropes of the folk tale. This is a story of imprisonment, escape, and transformation.

- Book 1 Title: The Lost Woman

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $32.95 pb, 280 pp

Smith grew up in Wellington, New Zealand, and moved to Australia when she was twenty-five, after four years of psychotherapy. The memoir concludes as her plane takes off for Melbourne, leaving behind the nightmare of life with her family. Dysfunction is a word that springs to mind, but it doesn’t do justice to the details revealed in the story. The father is always referred to as ‘my father’ while the mother is always ‘Mother’; each time it appears that proper noun is chilling. It is like a horrible name, rather than the descriptor of a parent.

The prose is plain, the structure straightforward, these strategies serving to emphasise the eerie horrors of the events. It is remarkable that the writer, who is the victim throughout the narrative, is able to share the story without resorting to expressions of hatred or any desire for revenge. From childhood to her twenties, the writer lived in an atmosphere of terror. She was sexually attacked and violently beaten: Mother ‘reached for the dog leash’ and ‘whipped me across the neck’. Above all the writer was relentlessly psychologically abused by Mother. She never succeeds in explaining Mother, concluding in the final chapter of the book that she was ‘a collection of behaviours’ that added up to ‘an enigma’. That puts it very mildly.

Until almost halfway through the memoir, the reader is as puzzled as the girl (who is never named) as to Mother’s background. Mother always said she had forgotten all about her early life. But as Mother gradually gave a few details, the girl learnt that Mother came from an island 830 kilometres east of New Zealand, and was part Maori, part Moriori. The Moriori are the original island people whose lives were changed by the coming of Europeans and Maori. Mother laughed ‘with pride’ when she described how her father Tiwai starved her sister and chased her with an axe, threatening to chop her up. Had Mother also suffered? The island was a wild and lonely place. ‘It was as if, having grown up on Chatham Island, she had modelled herself in its likeness and couldn’t unmake it.’ Frequently, the writer says that she cannot abandon Mother who is ‘all alone in the world’. The twisted bond between the two of them is incredibly powerful. The physical descriptions of Mother are truly horrible; she is grotesquely fat and has a tooth described as a ‘vampire’s fang’, which dents her bottom lip. Add to this the fact that she carries her handbag like ‘the Queen of England’. Curiously, one way of punishing her daughter is to force her for years to go to ballet classes against the girl’s will. Apart from psychotherapy, how did the writer succeed in making her escape and getting on the plane to Australia?

Remember Rapunzel. The child has a book of fairy tales, and her favourite place is the library, which is ‘filled with light, and fragrant with floor polish’. It is with considerable relief that the reader reads those words, since most places described are of the nature of the backyard, which ‘stood waist high in rye grass, wild wheat and fennel’. The girl is a compulsive and omnivorous reader, literature being one of the motifs of the memoir. Interestingly, Mother is also a dedicated reader, her books of choice being romances published by Mills & Boon. But the reading leads to writing,and writing will bring about this girl’s transformation. Her brother has torn out all the pages of the book of fairy tales, so the girl uses the cover boards as the folder for her own stories. These stories are essentially rape narratives, and the writer can’t understand how it is that she is thinking them up. ‘I know something is wrong with me,’ she says. ‘My story is me.’ She sees that her family life is full of ‘strange folds in logic’, and it often seems that if she could ‘read the signs correctly’ the mystery would ‘part like a curtain’ and she would find herself in a world where everything is ‘beautifully simple and clear’.

Well, she doesn’t exactly read the signs, and the world may not become simple, but she does write her way out. The conclusion of the memoir takes the reader back to the beginning when the nine-year-old girl longed to escape by running into the traffic, only to be saved by a vision of her adult self, which said: ‘Wait until you’re grown up. Then you can leave.’ She waited, she went through hell, she survived to tell the tale.

Comments powered by CComment