- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Deltroit (pronounced del-troy) is an exceptionally fine pastoral property and homestead in the Riverina – ‘pastoral’ in the Australian sense, with drovers, not shepherds, and the furies of fire, flood, and drought never far from mind, notwithstanding a privileged life in magnificent surroundings:

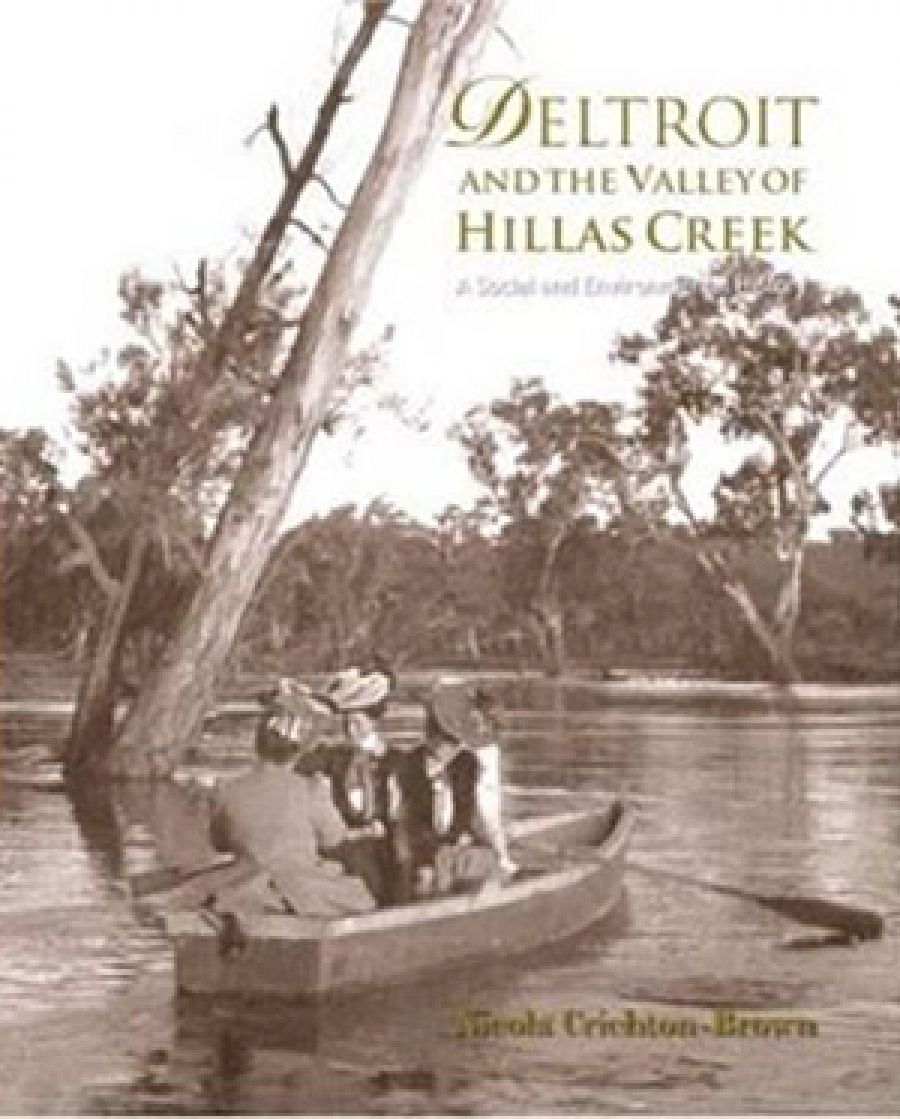

- Book 1 Title: Deltroit and the Valley of Hillas Creek

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Social and Environmental History

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne Books, $45 hb, 315 pp

- Situated at the junction of the South Western Slopes and the far eastern Riverina, a legendary grazing area of New South Wales, Deltroit lies halfway between Sydney and Melbourne, 30 kilometres south of Gundagai. Here the property extends on both sides of the Hillas Creek along a narrow but fertile valley.

Nicola Crichton-Brown’s history of Deltroit began its life as a project to assuage her loneliness on being transported there from London, the site of her birth, education, early working life, and first years of marriage. Thoroughly acculturated in the pleasures of the great metropolis, she was decidedly not like Dr Johnson’s construct – a person sick of London, sick of life. Nothing in her previous life, including strong Australian connections, quite prepared her for her new marital home and ‘the immutable silence that cloaked the homestead and garden, broken only by the occasional cockatoos or the demonic laughing of kookaburras’. The resulting book is part settler narrative, part social and environmental history, and part memoir.

The Deltroit homestead is not only of great architectural interest; it is also a palpable reminder of that happy conjunction, for some, of significant land holdings and the generation of wealth and prestige through the fabled wool prices of buoyant times. Crichton-Brown notes that it ‘has been estimated that between 1861 and 1891, sheep numbers in the Riverina climbed from one to thirteen million’.

The book opens with Deltroit’s geography, current size (just under 6500 acres), and an acknowledgment of the timeless landscape. Then an etymology of ‘Deltroit’ is essayed – perhaps it is derived from a word of the local, but quickly dispossessed, Wiradjuri people, dhaldhuray, meaning ‘having food’, or maybe ‘an eating or feasting place’?

As might be expected, Deltroit’s history over more than 150 years is largely revealed through biographical sketches of those connected with it and descriptions of focal aspects of the surrounding community. As with a good deal of such writing, part of the reader’s pleasure comes from the accretion of detail. Lineages, and there are quite a few, are saga-like in their brevity (aptly as it turns out):

William Richardson, who established Deltroit in the mid-nineteenth century, was born on Christmas Day 1839 in Bleatarn, a tiny hamlet of six houses in the Parish of Warcop, County of Westmorland (now part of Cumbria) in the far north-west of England. His parents were Michael Richardson and Dorothy Dent, the offspring of yeoman farmers from nearby Sleagill and Southby respectively.

After arriving in Australia aged seventeen in 1857, and enjoying successful starts as carters on the goldfields, William and his brother John became beneficiaries of the Robertson Land Acts of 1860, which threw open Crown Lands (previously under pastoral leases) for conditional acquisition (requiring purchase and improvement) by selectors. Some 320 acres could be selected before survey, and three times that amount of adjoining land could be leased. While records are too imperfect to determine the precise pattern of acquisition by the Richardson brothers, by their shrewdly chosen additions they accumulated, over time, the strategic land holdings now constituting the property.

Crichton-Brown occasionally laments the dearth of archival material, but the results of her meticulous research are evident. How delightful it is to learn that William spoke Cumbrian, the loose-vowelled brogue of far north‑west England, characterised by occasional Old Norse words in place of Standard English, and that Masonic meetings in rural Australia in the nineteenth century were fixed for nights of full moon to ensure that no one lost his or her way. Such minutiae, subsumed into the narrative, give the prose a winsome and stylish quality. There are also perceptive musings on the architecture, the garden, shared pastimes, pasture management, and much else besides.

By the time of Federation, after the vicissitudes of forty years of farming, William was wealthy beyond any Westmorland dreams of avarice. The grand homestead built in 1903 (after his children were grown up) was designed by Sydney architect William Mark Nixon in a composite style encompassing English and Gothic features. Vernacular concessions include the single storey under a large multi-gabled roof, and wide and shady verandahs.

Deltroit remained in the ownership of ancestors of William Richardson for another two generations. It later passed into corporate hands, then returned to private ownership. Owners had to contend with droughts and economic depressions. Mistakes were made. Money, crops, and stock were lost, and parcels of land sold off to reduce indebtedness. All this is amply described. The semiotics of reversal and renewal are not lost on the author or her husband. They have unfeigned respect for the continuity and human effort necessary to sustain the beautiful spaces they inhabit as respectful custodians, as much as owners. Further, in Crichton-Brown’s hands the history of Deltroit illuminates the social and environmental changes which have shaped so much of modern rural Australia.

Crichton-Brown’s sense of personal rescue through the love of a special place ensures that she does justice to Deltroit and to those who have lived and worked in its orbit. However, the book, splendidly produced and beautifully illustrated, is captivating for reasons far beyond that. It deserves a wide audience.

Comments powered by CComment