- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Why is the measure of love loss? As I worked my way through the hundred vignettes that comprise My Hundred Lovers, my thoughts kept returning to this first line of a novel by Jeanette Winterson that is similarly preoccupied with the interlinking of the body, love, sex, and death. My Hundred Lovers is the story of a life rendered as a litany of bodily memories. The twin-faced abstractions of desire and loss have lured and impelled the narrator through her worldly existence; this is a journey of self-formation made through metaphors of desire and dissolution.

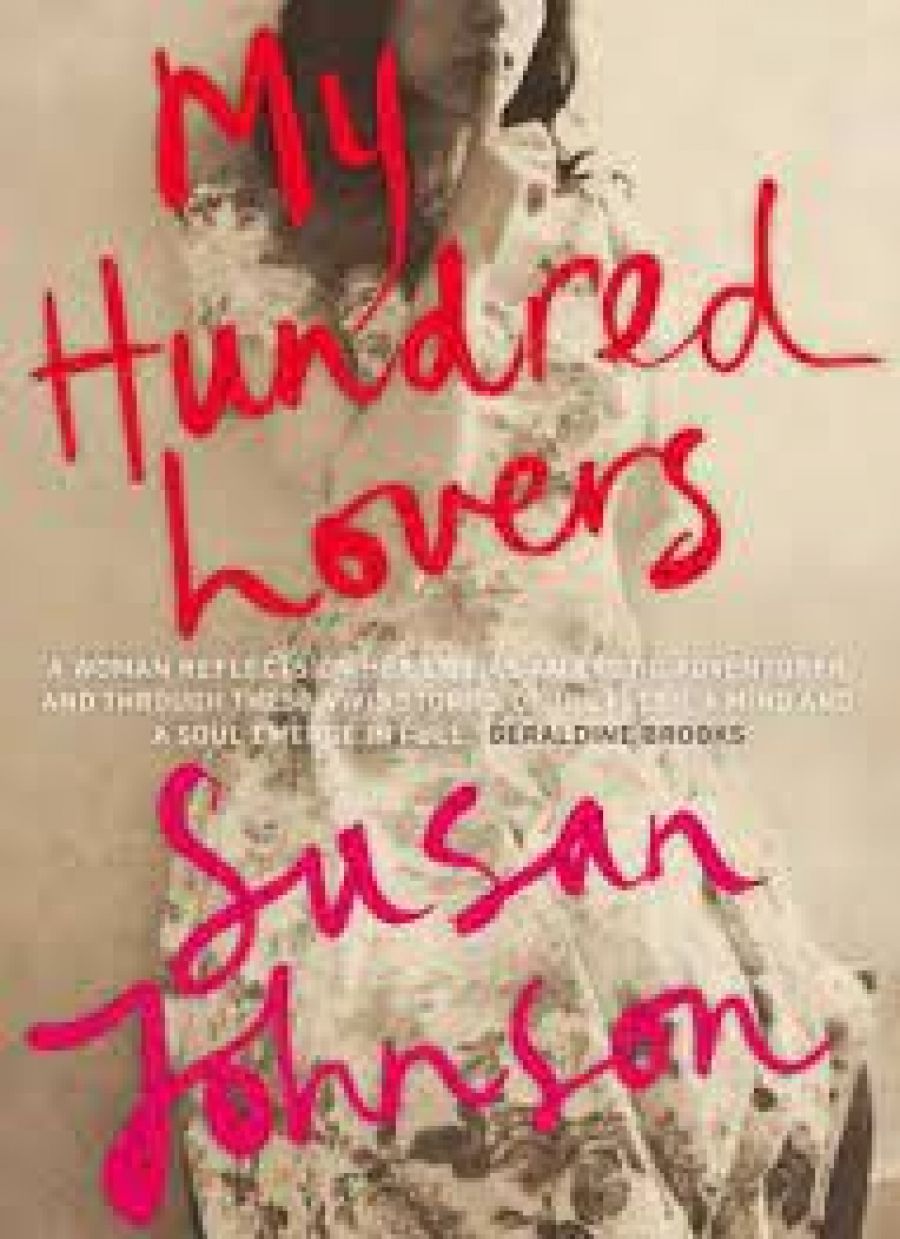

- Book 1 Title: My Hundred Lovers

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $27.99 pb, 278 pp, 9781741756357

On the eve of her fiftieth birthday, Johnson’s narrator takes stock of her life and expresses it in terms of a ‘lifetime’s sensual adventures’. The one hundred-strong cast of seducers is both discriminate and diverse: it includes physical objects, sensations, phenomena, and people. Reconstructing and documenting past loves precipitates a plunge into a sea of sensation and ardent emotion. Remembered love affairs are with family members and lovers, but include the kiss of sunshine and the feel of grass under bare feet, savouring the perfect croissant, the physical caress of rain or hotel sheets.

My Hundred Lovers is a sustained meditation on the body and the memories it holds; the body as physical entity and objective correlative of ourselves. The narrator wonders, ‘Can a body, confined to the modest compass of an ordinary skin, tell you everything?’ Structurally, Johnson plays with form and refuses a traditional narrative line. While in many respects linear – a general trajectory of the self from infant and adolescent and the more complicated world of adult desires – Johnson invites the reader to work with the book, using the memory fragments to piece together a whole self. The narrator’s body offers knowledge that is interpreted through the senses, the proposition being that the body is never purely physical but rather must be thought of as a social topography.

This is a work that is consistently revelatory about the phenomenon of love and its role in self-definition. The narrator affirms that ‘once a person loses the memory of desire, the ability to understand the difference between want and its absence, between happiness and unhappiness, the most fundamental apprehension of existence is lost’. As she recreates the contours and anatomy of desire through her body’s rememberings, the interplay of self and body preoccupies the text. Losing possession of the body signals waking death: ‘Disembodied from the memory of touch and want, from the remembered breaths of lovers and children and friends, a self is vanished.’

The dynamics of discovery and representation are couched in a framework of nostalgia and loss. The body in question is an ageing one: ‘in the months leading up to my fiftieth birthday I observed the first tentative signs of life’s waning […] My body was in the thrilling first flush of its death throes.’ The narrator’s new awareness of her own waning prompts memories of the decline of her mother and her grandmother; her anxiety compels the chronicling of ‘the humble stories from [her] body’. Personal history is presented against history writ large – there is a play on bit players, calling attention to the fact that the narrator’s unique history is unremarkable in a sea of billions but is also meaningful in its singularity. She wants to capture a life made manifest before it is too late: ‘I want to record the lips, the fingers, the belly, the tongue, before I forget they are mine.’ For it is clear in the novel that death comes too late: the final dissolution affects others, but not ourselves.

The ephemerality of youth is reflected in ‘dissolving present moments’. Even a croissant is described in terms of imminent waste: ‘Such a brief perishing object! So full of life, yet evanescent as the most fragile butterfly, dead by day’s end, its flowering over within hours.’ Many of the vignettes are simultaneously celebratory and consistently elegiac. Sex and death are consistently linked, most obviously so when a new threat looms in the form of Aids. Suddenly her body, once a vehicle of carefree pleasure and self discovery, becomes menacing. There is a telling section when the narrator reflects on her suite of physical lovers and wonders ‘wasn’t it possible that her body was polluted, that in truth it was a shameful dark thing, too little loved?’

Johnson draws from the visceral and the pulse of the body’s drives as she explores how sensual experiences of touch, taste, hearing, and smell have the capacity to invoke rapture. This work is earthy, fixated with sensual and embodied experience, but also philosophically rich. I have always found Johnson’s writing to be lush and luxuriant, celebratory and honest, and the conceit of this particular work seems perfectly suited to her style. Occasionally, the unabashedly ornate and metaphorically laden language teeters on the edge of hyperbole.

Johnson considers love’s ability to shatter and heal simultaneously. She does not shy away from grief or joy, and she explores how love can both transform and wound. Most poignant of these could be the unmaking of self in the face of perceived true love. On falling in love for the first time, the narrator abandons all senses and finds herself deaf, dumb, and blind to anything but her lover’s face. Again, the capacity to love entails the experience of loss. Loving someone else destroys her ideas of who she is and what she wants: priorities change, friends change, houses change, she changes, and love impels the formation of an ideal outside of oneself. She sees her future written on someone else: ‘My future husband had horizons in his face.’

As I reached the seventieth lover, I began to wonder how this might end and whether I would be satisfied. I was. Johnson’s writing is sensual, intimate, and deeply moving as it salutes the joys and foibles of romantic love, familial love, and maternal love.

Comments powered by CComment