- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Five years after Michelangelo Antonioni’s death, the ground-breaking Italian director’s films occupy an increasingly important but odd position. Exemplifying serious ‘art cinema’ at the peak of its European expression, his most famous work continues to compel yet also cause problems for critical reception. How to write about such demanding and endlessly rewarding films without falling back on what we are often told are the old clichés of ‘alienation’ and chilly formalism? A welcome addition to the slowly percolating appreciations of the film-maker in English, Antonioni: Centenary Essays quite visibly, if not perhaps intentionally, struggles with and exemplifies this challenge.

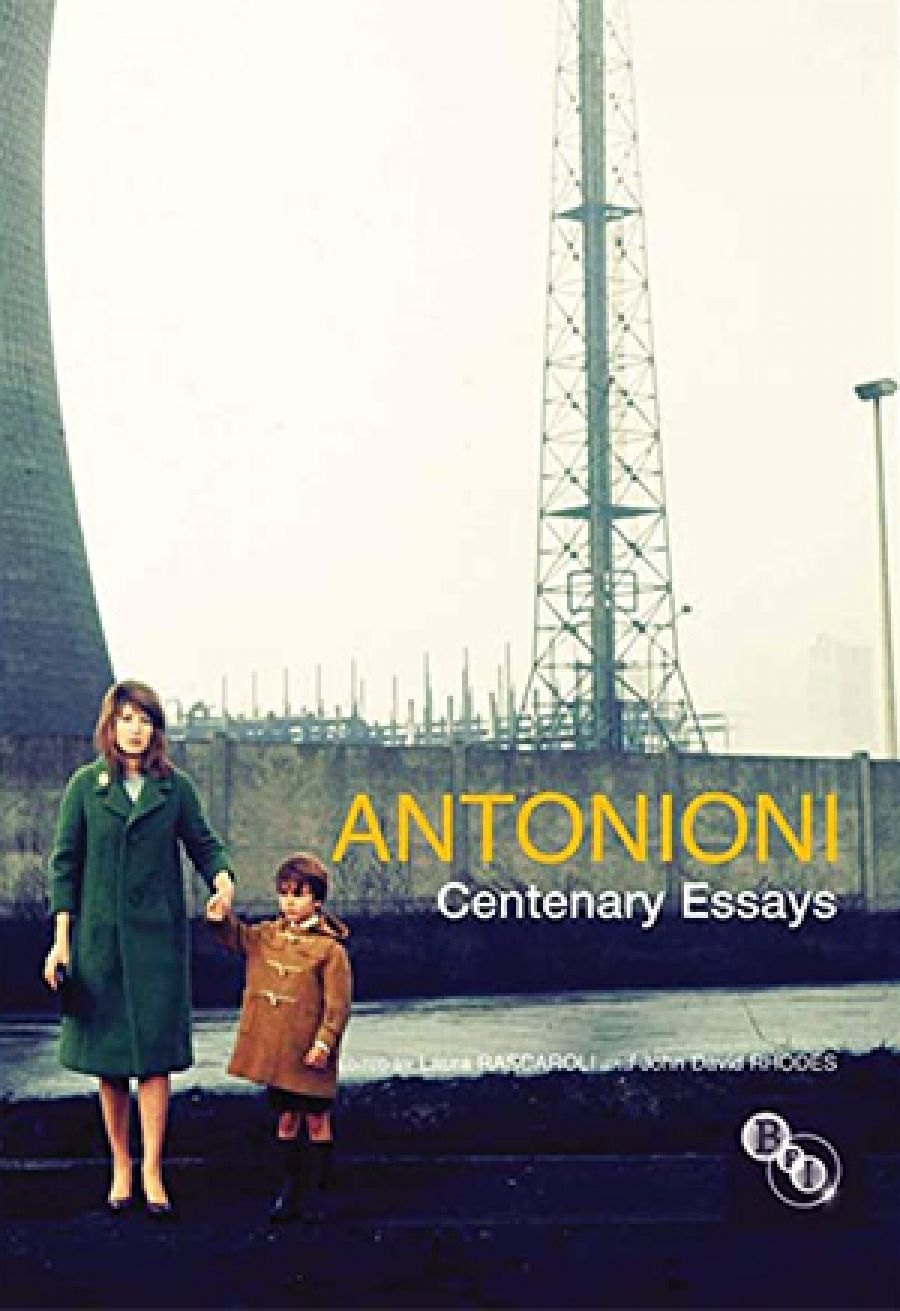

- Book 1 Title: Antonioni

- Book 1 Subtitle: Centenary Essays

- Book 1 Biblio: Palgrave Macmillan/British Film Institute, $44 pb, 337 pp

As elsewhere in the humanities, an often productive ‘historical turn’ has marked academic film studies over the last decade or more. Many of the essays in this volume, however, exhibit signs of this shift having reached a point of excess. They often tell us less about the films’ own histories and more about their broader historical moments or of the prime industrial and economic materials shown on screen (such as the role of petroleum-related manufacturing in Italy’s postwar economic recovery, the history of photography as a way to understand pop culture in mid-1960s London, or the legal and political history of Italian television upon the emergence of private local stations). In the process, the book’s declared topic – Antonioni, his films, and their directorial authorship – recedes from view for long intervals.

There is certainly much to be gained by a film being addressed in its historical specificity, but in many of these essays multiple pages at a time can read like elongated footnotes – sometimes interesting, often more laborious – offering contextual minutiae that could just as readily apply to other films (or none at all) as Antonioni’s. This problem connects to a more specific one concerning Antonioni scholarship itself.

If a reader comes to these essays direct from an inaugural or refreshed experience of this director’s extraordinary cinema, after reading their 300 pages (plus extensive notes) she would likely emerge better informed about the broader technological, industrial, and economic details of life in Italy and elsewhere at the time these films were made than about precisely what historical and ongoing claims scholars make for them and what it is like to watch one. This is partly because the book quite self-consciously sets out to avoid the familiar ‘Antonioni language’.

It is of course entirely legitimate and often necessary not to offer a first port-of-call account of a film-maker’s work and instead seek to open up new areas of research; and the best of the essays do so in generative ways. But these particular attempts to forge new ground often come at a price.

Most glaringly perhaps, the reader may be puzzled that while many of the director’s lesser-known and historically ignored or derided works – such as Il Mistero di Oberwald (1980), Identificazione di una donna (1982), and the short Il Provino (1965) – but also the early documentaries, particularly Gente del Po (1947) and N.U. (1948), receive whole chapters or substantial parts thereof, Antonioni’s seminal films of the early 1960s receive disproportionately limited attention considering their historical and lasting importance.

While the documentaries are both over-represented in the book and often the subject of repeated historical details and analytical points (the essays often even cite the same secondary sources), the surely more important L’eclisse (1962) is denied sustained analysis, while La notte (1961) is discussed even less. And when the former film – which I and many other Antonioni enthusiasts considerthe director’s supreme achievement – is addressed, the points of reference – mainly its quite revolutionary opening and closing sections (given most attention in co-editor John David Rhodes’s essay) and well-known use of Rome’s unique EUR district (best detailed by Jacopo Benci) – are again often repeated.

The book’s ‘egalitarian’ coverage of Antonioni’s career goes beyond the desire to treat a famous director’s body of work in an internally ‘non-canonical’ way so as to explore neglected corners and to mount new, perhaps revisionist, arguments. The substantial historical writing devoted to L’avventura (1960), La notte, L’eclisse, and Il deserto rosso (1964) seems to have inspired an unconscious scholarly backlash. This volume’s self-conscious ambition, clearly stated in its Introduction, to overturn or bracket the purported clichés of Antonioni criticism has had the effect of suppressing, at least in part, a more explicit confrontation with the imposing but endlessly rewarding and historically most discussed films that made the director’s global reputation. Meanwhile, his prominent English-language productions – Blow Up (1966), Zabriskie Point (1970), and The Passenger (1975) – are each treated to a decent chapter apiece, despite also being much written about since their release.

When the famous early-1960s works are addressed, the essays often enact vaguely ‘contemporary’ and would-be revisionist treatments. So Il deserto rosso is primarily examined through what Karl Schoonover calls the director’s interest in ‘waste management’, and what Karen Pinkus rather more confusingly asserts is the film’s prescient meditation on global warming. Demonstrating the academic interest in issues of acting and performance over many years now, in another essay David Forgacs usefully addresses Antonioni’s unusual treatment of actors, with some particular attention to Monica Vitti’s highly distinctive presence in the films of the early 1960s. Meanwhile, Rosalind Galt’s effective reading of the director’s use of Sicily in L’avventura is arguably of most interest for reclaiming a notion of the picturesque (a heritage that is again detailed via many pages of historical material beyond the film).

While the almost unique ambiguity of Antonioni’s cinema (the key, Roland Barthes famously argued, to its special status as properly ‘modern’) tends to encourage wide-ranging readings, the reader of this book is left rather unenlightened as to why the still-challenging but aesthetically ravishing and philosophically suggestive early-1960s work has caused so much debate, criticism, and adoration for more than fifty years.

The editors’ Introduction does gesture towards L’avventura’s infamous 1960 Cannes première, at which it was violently jeered for narratively unmotivated sequences (before receiving a special customised Jury award). Yet none of the subsequent essays seeks to grapple with the multiple ramifications of this almost-mythic founding scandal of postwar feature film modernism, or to ask what relationship Antonioni’s work from this important period now has with digital-era audiences.

The best essays in the book offer valuable sources of information, often painstaking research (some valuable Italian archive documents and articles are quoted in translation), and scholarly insights. However, while the apparent desire to get past the declared clichés of Antonioni criticism is understandable, it can also take on slightly repressive qualities. Key films showing his work at its most demanding and rewarding – formally and aesthetically radical (remaking the role of space and time in narrative cinema), thematically suggestive yet highly ambiguous, mysterious, and substantively philosophical – remain under-analysed in the book, seemingly as a result of having been so extensively written about, often in startlingly direct evocations of this cinema’s primary thrust, since the early 1960s.

Antonioni: Centenary Essays shows that Antonioni’s films, which have long challenged the language of narrative cinema and that of film criticism and scholarship alike, remain perhaps more elusive than ever.

Comments powered by CComment