- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

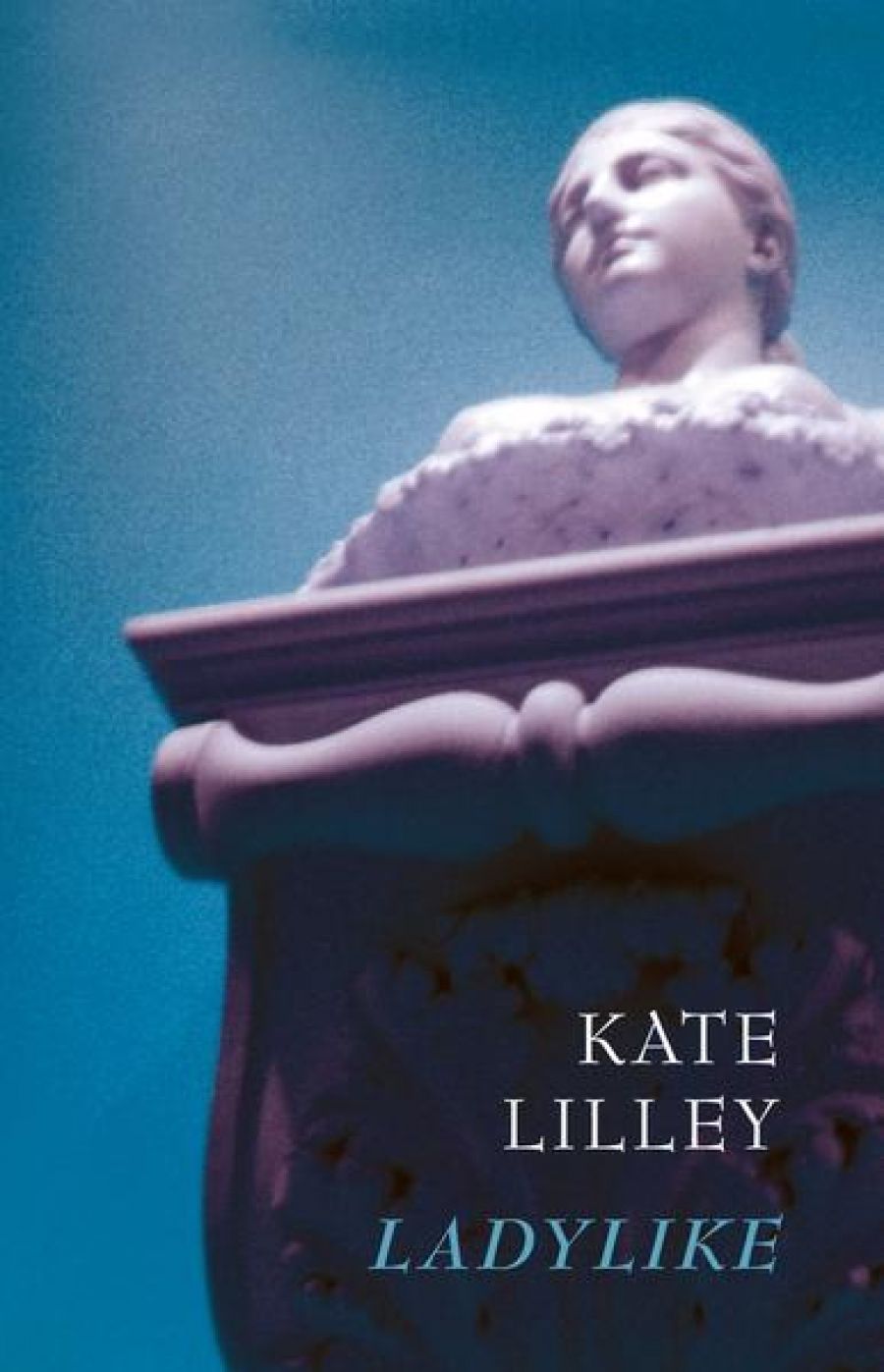

Like all good titles, Kate Lilley’s Ladylike offers the reader a coded and evocative entrée into her new collection. These poems are concerned with exposing and critiquing some of the expectations of femininity, of being ladylike, as found in the past and the present, in contemporary cultures such as the cinema and in the discourses of the academy. The idea of ‘liking ladies’ is also central to these poems, as a current of desires that cuts across more conventional notions of the lady. The title also suggests a motif of mirroring, even doubling, where a self is similar to, perhaps even indistinguishable from an ‘other’, and yet is also simultaneously different, a simulacra or sign that can never be the thing in question. It is within this point of slippage – this petticoat slide between an embodiment of femininity and its repetitions or likenesses – that Lilley’s poetry operates, generating a reading experience which can be both vertiginous and full of the rigour of possibilities.

- Book 1 Title: Ladylike

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $19.95 pb, 86 pp

In her prose Introduction, as well as in the first section, ‘The Double Session’, Lilley explicitly links the idea of doubleness to the faceted experience of psychoanalysis, the cordoned fifty minutes in which a private self has room to explore, even play. The interiority of that self is also twinned with the self that leaves the room, catching the bus to the university in order to deliver her own fifty-minute insights in the form of lectures. The private self, the professional self, the daughter, the equal, the mourner, the sharp, probing, witty voice: all are given space both within the room of the session and, by extension, within the chamber of the poem. ‘Sessions are like dreams,’ Lilley writes, ‘absorbed into a rhythm of speaking silence and thinking aloud […] a sublime threshold, repeatedly redrawn.’

In the section ‘Cleft’, dedicated to Dorothy Hewett, Lilley explicitly considers both the complexities of her relationship with her mother and the residual effects of grief and mourning. Hewett – poet, playwright, activist, and large-canvas personality – is, on important levels, the Lady who must always pervade and influence the woman who, like her, is both poet and intellectual. The tension and bond between these two formidable writers is teased out in the punning ‘Dress Circle’: ‘Melodramas are made for mothers. / The daughter thinks that one day / she’ll graduate and take the lead. / Your right hand, little amanuensis …’ However, the youthful fantasy of ‘graduation’, of moving in a straightforward and linear fashion out of a relationship of dependence and reversing the balance of power, is counterbalanced by the strong call of the past, the recurrent mourning at the loss of the person of the mother. ‘Now I’m off the hook and at a loss … / what’ll I do without you?’Or as Lilley writes in the poem ‘Coil’, with its implications of complexity and looping backwards as well as forwards, ‘You go on living / happen never happened.’

Lilley’s poetic style is generally associative, sometimes using extra-logical linkages between words and images – sometimes these are metaphoric images, sometimes a juxtaposition of text with a collage of visual images that problematise both the genre and the reading experience. These poems don’t take a reader in an expected direction. Images and ideas are juxtaposed in sometimes disconcerting, sometimes amusing sequences, such as in the poem ‘1-800-DENIED’: ‘Take this watch in token of my etc. / Glycerin pardon, barometric rage. / Now the dust jacket bears your name you have to wear it.’ Sometimes there is a playfulness and repetition in the use of language that, Gertrude Stein-like, disrupts any overly close relation between sign and signified. Take for example, ‘LITTLE Maisie’: ‘poor LITTLE monkey deep LITTLE cup LITTLE …’, or the inventory of adverbs in ‘Maisily’: ‘confusingly immensely peculiarly soothingly brightly gravely …’ If the poem is akin to a dream, or psychoanalytic session, Lilley makes use of language, in all its weave and coil of suggestiveness, to take the reader into uncharted territory, to the cusp of inside and outside, the flickering glance in the mirror.

Her interest in a motif of doubleness and, by implication, the theory of the unconscious, is also apparent in the section ‘Round Vienna’, with its revisiting of some of nineteenth-century psychoanalysis’s most significant women: ‘Fraud’s Dora’, as she calls her, Marie Bonaparte, Sidonie, whose homosexuality so bemused Freud. ‘A girl may harden herself / in the conviction that she does possess a penis,’ Lilley writes, and concludes the section, and the book, with the line ‘Give her an inch!’ – an ironic and witty celebration of the power of the clitoris, the book’s ultimate penetrative space of ladylike-ness. Perched above what appears to be an image of Frida Kahlo’s headdress, rising resplendent over her obscured face, this ‘inch’ of female sexuality is ready to be taken for a mile, to romp toward its own pleasures.

Ladylike is a book heavily influenced by ideas – ideas of doubleness, dream, lesbian desire, an almost Irigarayen re-imagining of female sexuality, as well as the flexibility and playfulness of a not always referential language. It also makes use of aspects of Lilley’s own research areas, as in the section ‘Ladylike’s’ exploration of a seventeenth-century bigamist. Fierce in its intellectual enquiry, it is also a poetry of exquisite form, and consolidates the emergence of a strong voice in Australian poetry.

Comments powered by CComment