- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Papua New Guinea doesn’t loom large in Australian literature. As Nicholas Jose says, our ‘writers have not much looked in that direction for material or inspiration’. Drusilla Modjeska is thus entering relatively new territory for Australian fiction with an ambitious epic set in PNG. It is also a new venture for her: Poppy (1990), her only previous ‘novel’, won two non-fiction awards. She has said that ‘as neither term seemed right, I opted for both’ – autobiography and fiction.

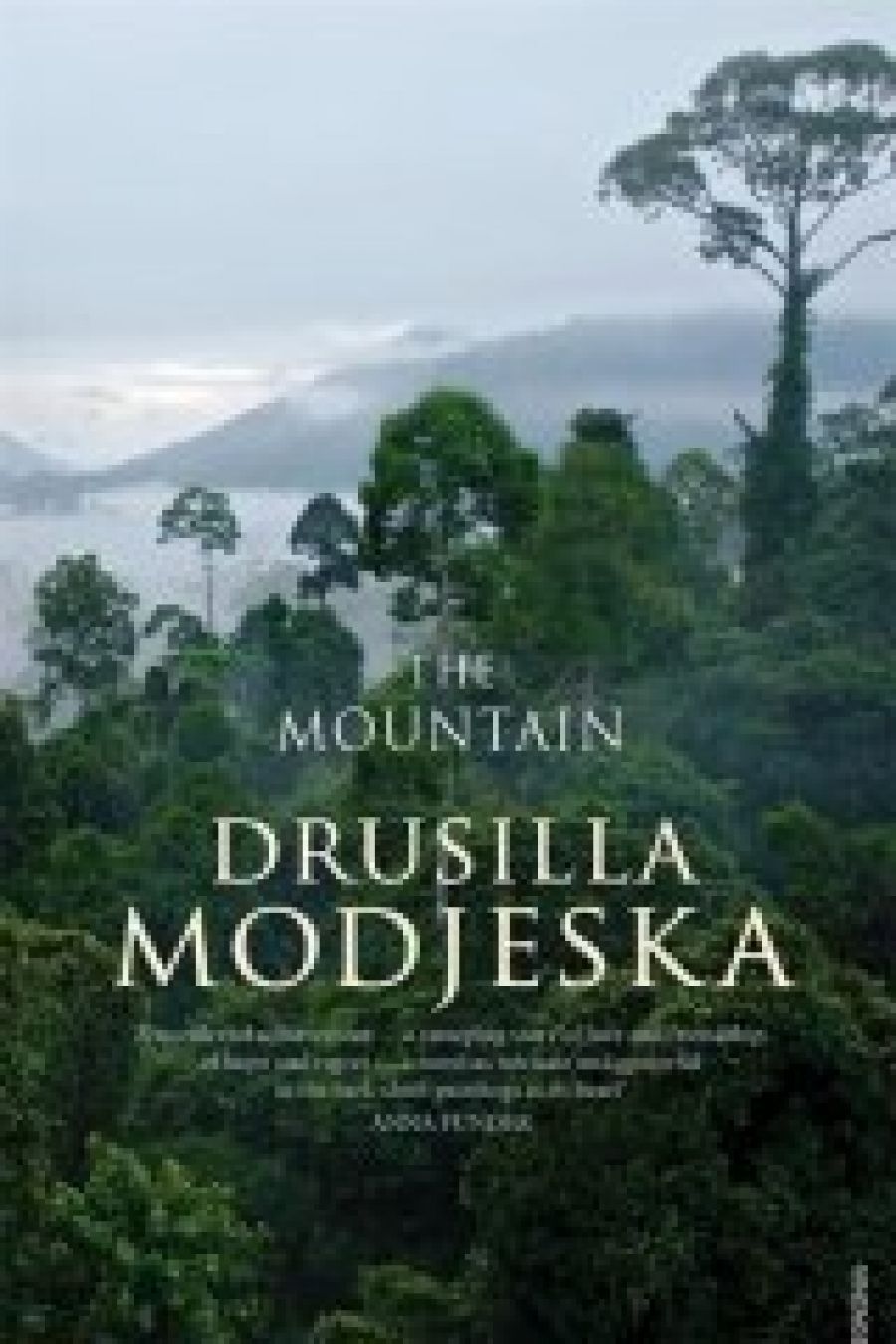

- Book 1 Title: The Mountain

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $32.95 pb, 464 pp, 9781741666502

The Mountain, despite its solid historical foundation, is unequivocally a novel. It concerns the years from 1968 to 1973, when PNG was moving towards self-government. Leonard, an ethnographic film-maker from Oxford, goes to PNG to make a film about an isolated mountain village. With him is his much younger wife, Rika. When he sets off for the mountain, Rika stays in Port Moresby with her new friends at the University of PNG. When she finally joins him, everything has changed. Although the second part of the book is set in the new millennium, the focus remains on this period – on the group of university friends and the stresses that eventually destroy their brief period of harmony. The half-in-half, or hapkas, theme is prominent. Many of the main characters are of mixed parentage, and others are divided in different ways: their Western education distancing them from their village origins, or, for the expatriates, their love of the country complicated by not belonging and by unease about their complicity in the pervading colonial situation.

While reading this long, serious novel, I often thought of Doris Lessing, not only because of the subject matter – a country in the late stages of colonial rule, like Lessing’s Southern Rhodesia – or even the coincidence of an author–surrogate named Martha, who one day ‘took out a clean sheet of paper and wrote “The Mountain” at the top’. Although Modjeska shares Lessing’s political awareness and her perspicuity about friendships, marriages, and sexual relations, it is certainly not the voice: Modjeska does not have Lessing’s peculiar mixture of mysticism and sagacious dryness. It is more to do with her implied expectations of her readers. I have never been sure whether Lessing’s apparent impatience with setting scenes, introducing characters, and so on, is in fact an intentional challenge to keep up, to work with her. Modjeska, likewise, brings in major characters without always observing the usual niceties of description and placement. With so many characters in this sprawling novel, when faced with a sentence like ‘The one threat to this happy view was Derek’, one is inclined to panic: is this a new character or am I supposed to be remembering him from one hundred pages earlier? However, as with Lessing, if one suppresses the panic and allows the narrative to unfold, all is usually made clear enough.

The point of view is often fluid, and sometimes even unspecified. Some moments of confusion – for instance, when Rika finally arrives, exhausted after hours of climbing, at the village where Leonard is filming – seem deliberately intended to reflect the character’s state of mind. At one point, a major character disappears from the scene without explanation for years, leaving a tense situation unresolved, the narrative taking a different direction when it feels as though it should be bringing this conflict to a head.

Then there is the tricky question of where the line between fiction and historical fact belongs. Leonard’s film is hailed as a turning point in ethnographic film. Since this is fiction, is there an ethical problem with inventing a white ethnographer who is fêted by indigenous PNG academics? As Modjeska explains in her Afterword, the characters, even those who are said to play an important part in PNG’s history, are fictional, though Michael Somare is there in the background, summoning Aaron, Rika’s second husband, from his university job to work for the government. Those in the know will no doubt make identifications, but it would diminish the novel to regard it as merely a roman-à-clef.

The Mountain, a wide-ranging book, is demanding at first. It encompasses many aspects of PNG’s recent history, and the suspicions and fissures not only between the whites and the people of PNG, but also within and between the country’s many different communities. Modjeska has much to say about the difficulties for someone like Aaron, whom ‘western education had pulled […] out of tribe and place’. He was not ‘able to live by temperament alone’, but was ruled by an ‘existential paradox that was like a curse’, and Rika can never understand this fact. Modjeska has much to say, too, about the nature of Australia’s involvement in PNG; about the brutal commercial exploitation the newly independent government has no power to prevent. The Australian Martha makes a study of colonial travellers in PNG, and eventually has an epiphany of sorts: ‘We used a different language […] but were we so different, all of us who came with “dreams of things longed for” and hearts to be unlocked?’ With so many competing views to include, and such a freight of complicity to be acknowledged, it is no wonder if initially the reader feels overwhelmed and finds it difficult to engage with the characters. But this mountain is worth climbing, and though at the top the view might not be unimpeded, this heartfelt, intelligent book cannot be disregarded.

Comments powered by CComment