- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

How much does the average Australian know about Indonesia? Not the tourist version, with its resorts and beaches and lacklustre nasi goreng – but the wider culture, history, and people. At best, Indonesia is a tantalising enigma to most Australians. At worst, it is ignored – a vast nation about which we neither know nor care, despite its importance as one of our closest neighbours.

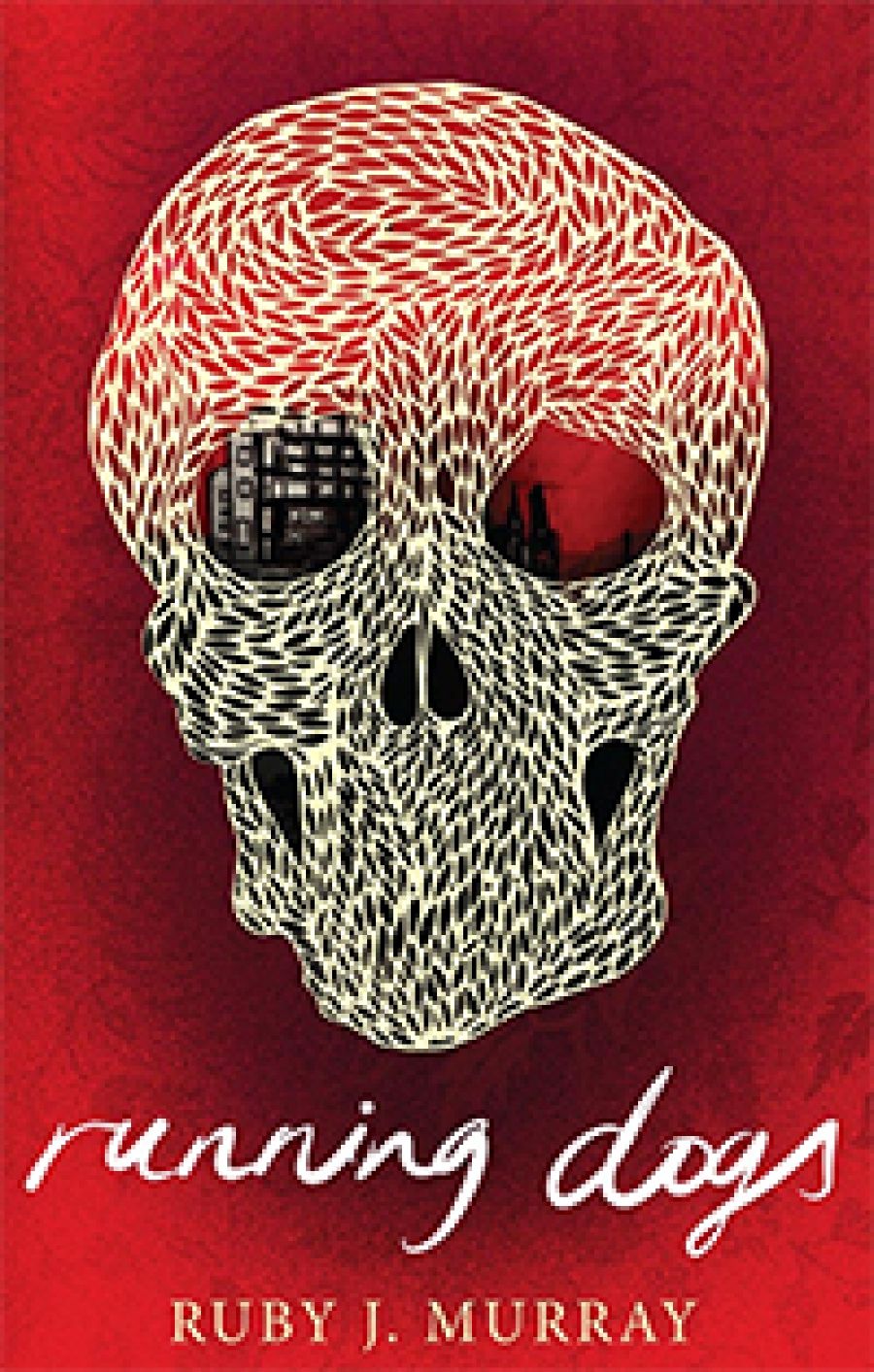

- Book 1 Title: Running Dogs

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $29.95 pb, 288 pp, 9781921844706

Running Dogs, the impressive début novel by Australian writer Ruby J. Murray, goes some way to redressing that ignorance. The narrative weaves together two time periods: the Jakarta of 1997–98, a time of great social and political unrest that led to the end of President Suharto’s thirty-one-year rule; and the post-Suharto transition period (known as ‘Reformasi’ in Indonesian) of present-day Jakarta. With this dual narrative, the novel sheds light not only on the violence, usurpation, and mismanagement that have hampered the nation, but also on the religion, animism, and sensuousness at the heart of Indonesia and its people.

Into the modern setting arrives Diana, an Australian in her late twenties who takes up a position in Jakarta at an NGO, the International Disaster Response Coalition. Diana is determined to make a difference, but her idealism crumbles in the face of her co-workers’ cynicism. On top of this, her attempt to instigate changes in her workplace to help the needy backfires. ‘We need a few more disasters or we’re going to have to shut up shop […] Come on, give us a tsunami already. Just a smallish one, enough to tie [sic]us over,’ jokes one of the aid workers, to cheer up Diana, and there is a kernel of truth in what she says. Diana’s spirits are further dampened when her resolve to mingle with locals by sitting with the Indonesian staff during lunchtime ends in humiliation.

Diana eventually reconnects with Petra Jordan, an old friend from her university days in Melbourne. Petra is a beautiful, wealthy, half-Indonesian socialite whose father, Richard Jordan, is a powerful American businessman involved in forestry and infrastructure in Indonesia. Petra’s father is the ‘running dog’ of the novel’s title, due to his ties to a large corporation. Petra and her two younger brothers, brooding Isaak and gentle half-brother Paul, are the apex of Jakarta’s élite: when they are not attending gala fundraising events and hosting lavish parties, they are out on the tiles at the city’s most exclusive bars and clubs. For all her good intentions, Diana finds herself drawn into the Jordans’ coterie and enjoying their extravagant lifestyle. But Diana senses that there is more to the siblings than their privileged lives would suggest. There is, for one, the mysterious work they perform for their father. Diana also suspects that they share a secret whose burden manifests in different ways: Petra’s aloofness, Isaak’s caustic streak, Paul’s anguish.

The 1997 narrative provides some answers, as we see the primary school-aged Jordan children negotiate a difficult childhood, dodging school bullies, vying for the affection of their uncaring mother, and placating their volatile father. Their only source of comfort is their nanny, Mbak Nana, whom they love and who is their emotional and spiritual core. Mbak Nana teaches them how to harness the power of the Javanese spirit Nyai Roro to protect themselves. But the dark force that the children unleash continues to haunt them in their adult lives.

The prose, slick and economical, moves snappily throughout. It is full of sharp observations that draw attention to the divide between the rich and poor and the grossly elevated status of expatriates in Indonesia: when Diana returns to her apartment block late one night, the cleaner riding the elevator hangs her head in shame as she has been sprung in the elevator meant for residents.

Murray writes in the concise manner of a journalist and with the keen sensibility of a political activist. The scenes set inside Diana’s workplace are depicted with an insider’s subtle mockery; it comes as no surprise to learn that the author once worked at an international development agency in Jakarta. What is surprising is how deftly she captures Jakarta through the eyes of the young Jordan children: the ripe smells, the exotic street food of fried gorengan and spicy sambal, the chaotic traffic, and the simmering tension of a city on the brink of collapse.

As the story builds towards its conclusion, the threads of the Jordans’ past, their father’s work, and Diana’s involvement come together. Just as the rubbish that fills Jakarta’s streets reflects the taint of corporate corruption, Diana’s arc is symbolic of the failure of international aid in Indonesia: from well-intentioned do-gooder to becoming mired in the complexities of the situation and losing sight of the big picture. There is a point in the novel when a character, overwhelmed with grief at losing a loved one, has a moment of release, like ‘one long inhalation coming across the space, bringing with it everything that they could have done differently’. It is a sentiment that could be applied to Australia’s general approach to Indonesia.

Although the momentum feels rushed towards the end – a few parts revealed through exposition would have worked better as scenes, and some narrative threads are wrapped up too quickly – Running Dogs is an enthralling and highly enjoyable novel that presents a convincing argument against ignorance and apathy.

Comments powered by CComment