- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Ornithology

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Fernando Nottebohm has been interested in birdsong since early childhood. By 2001 he had spent thirty years at Rockefeller University in New York studying how birds learn to sing, concentrating on canaries who are capable of learning new songs each year. His interest has been to study birdsong as ‘a model for the brain’. He studied the brains of caged birds and birds in the wild. The birds that needed to forage and escape predators produced more neurons in the hippocampus, the part of the brain that is essential to memory.

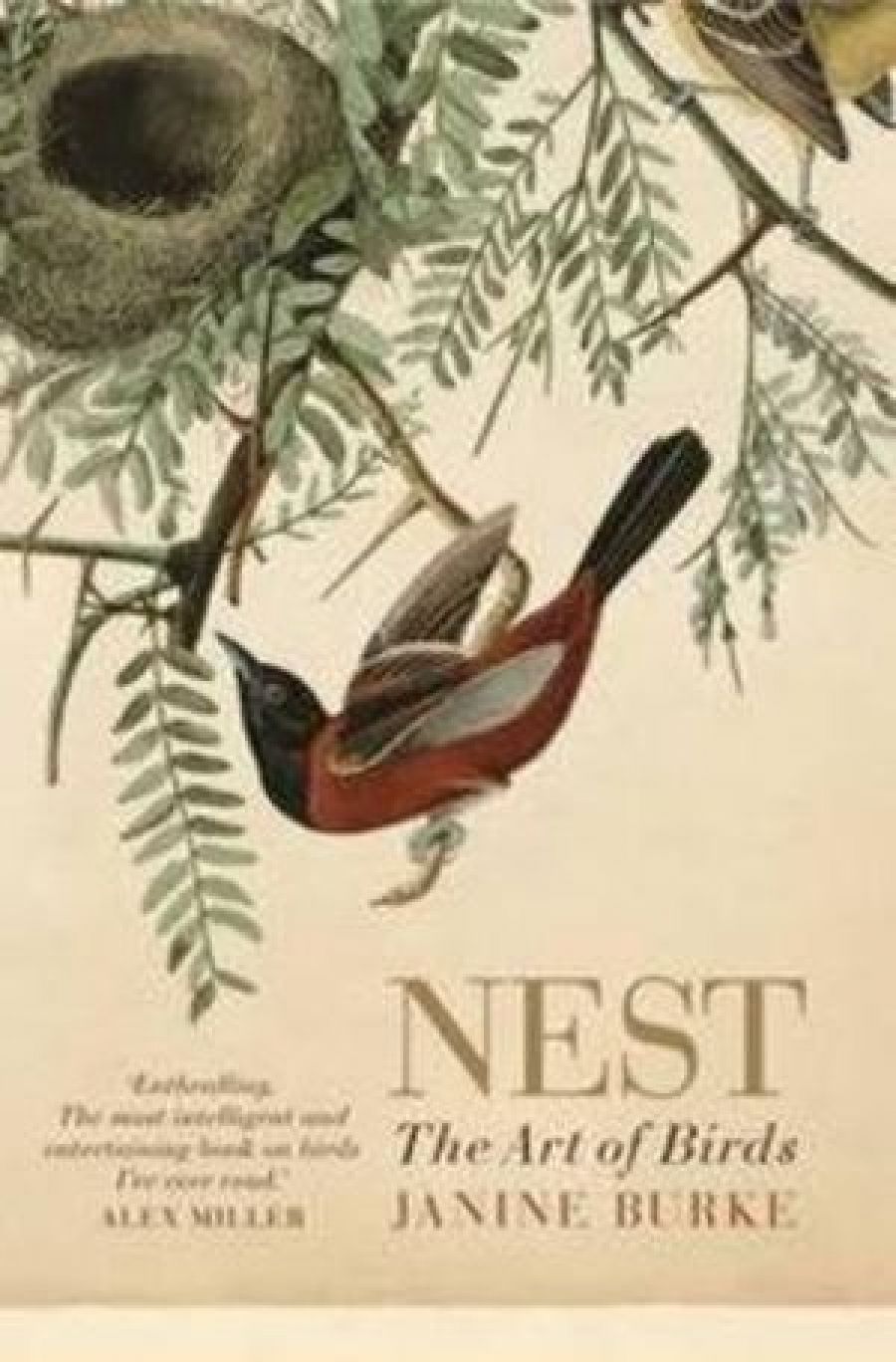

- Book 1 Title: Nest

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Art of Birds

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 hb, 182 pp, 9781742378299

Using bird brains and remarkable new scientific technology, Nottebohm and his students showed that birds, both young and old, produced thousands of new neurons every day. The evidence of nerve cell regeneration – neurogenesis – overturned the long-held view of the brain as an unrenewable organ, and has had a profound impact on research into diseases such as Alzheimer’s, and brain injuries. But in the beginning, Nottebohm told the New Yorker in 2001, ‘I wanted to discover lovely basic things and I wanted to listen to the music of the birds.’

Janine Burke is an art historian, a novelist, a biographer. Her new book is a divergence of a kind, personal, full of digressions and insights, and, as we would expect, meticulously researched and structured, although it is far from academic. Burke’s argument, winding its way through the book, often lost and then found, is about the nature of art. Writing about the bowerbird’s nest-making, she refers to Darwin’s suggestion that both the male (the nest-maker) and the female enjoy ‘a sense of beauty’, an aesthetic sense. Mike Hansell, the author of a book on animal architecture, suggests that ‘bowerbirds might be artists’.

Early in Nest, Burke describes an installation, made in 2010, by Christian Froelich, a ‘monumental yet fragile’ nest made of twigs and rose brambles. At the close of the book she describes an installation by Céleste Boursier-Mougenot at GoMA, in Brisbane. Live finches (zebra, double-bar, gouldian, crimson) sang as they alighted on coat hangers suspended from harpsichords, so the soundscape was complex, part man-made, part bird-made.

This second installation is much more in keeping with her central enquiry: ‘what if the urge to make things carried with it an inherent desire, in the case of humans and perhaps of some highly intelligent birds, to make those things beautiful?’ She quotes from animal behaviour researchers James Gould and Carol Grant Gould, who saw that bird architecture is full of individualist variability that ‘in humans we would call aesthetic’.

French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, building on their premise that ‘composition is the sole definition of art’, define the bowerbird as ‘a complete artist’. This is because, explains Burke, the combination of colours, postures, and sounds become ‘“a total work of art” that we as humans can appreciate’. This argument embodies the crux of the problem for many of us, and is the knot that Burke is trying to untangle and make again. The human observer is the only voice raised in support of any theory about animals as artists. It is a human thesis that birds have no interest in, no quarrel with, no quibble to tweak at, no compliment to preen over. Whether they be artists or not is not something their brains self-consciously dwell on (insofar as I try to understand the neuroscience and as far as neuroscience might show evidence).

This reader is more inclined to marvel at the sublime craft of nest building, and only then to see some nests as beautiful. The Australian artist Fiona Hall made a remarkable work (‘Tender’, 2003–06) based on copies of many different nests, all of hers woven with shredded American dollar bills. Aside from making social and political comment, Hall met craft with craft. But whether birds, in building complex and aesthetically pleasing nests, are artists, is not simply a question of human perception. Burke asks whether the birds themselves have an aesthetic sense. If they do, then this sense has been, in evolutionary terms, successful.

Between the introductory chapter and the last are four chapters that address her thesis only tangentially. The poetry of nests (and in large part these poets address song as much as architecture) is exemplified through Keats, Shelley, Frost, Dickinson, Wordsworth, the usual culprits, but also through John Clare, a peasant worker, a ‘madman’, and a poet to treasure. One of his sonnets, ‘Emmonsails Heath in Winter’, is a glorious song to place, nature, and especially to birds.

Holding a nest for the first time in 2010 was a pivotal experience for Burke. As an art historian and curator, she had expected strict rules at the Melbourne Museum, but she was left alone to handle the nests in storage. From my

own experience as an admirer and collector of nests, even the most fragile, even those that are hardly more than a pile of fiddlesticks, or a tiny lace bag, are extraordinarily resilient, the embodiment of intelligent building techniques, of craft. These delicate nests often show more resilience than mud-bound nests, which in the main have little aesthetic appeal. Burke describes the willy wagtail’s nest in the museum as mud and ‘about seven millimetres across’. This measurement is surely an impossibility, perhaps an editorial glitch, and willy wagtails do not build mud nests, although the nest is a tough little trough bound over and over again with cobwebs to the branches which support it.

Perhaps the answer to Burke’s questions about the nature of art, and whether birds are artists, lies in what she herself brings up in Nests: that some philosophers are now asking not what is art, but ‘What is nature?’

Comments powered by CComment