- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Portrait of a sea-green enigma

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The ‘good’ biographer always opts for a nuanced portrait, and this is what Peter McPhee has given us in his well-written, reflective, sympathetic account of one of the most enigmatic, complex leaders of the French Revolution, Maximilien Robespierre (1758–94). McPhee had his work cut out for him. Those familiar with the period may come to this book, as I did, with somewhat preconceived ideas. Robespierre conjures up a rather distasteful character, a revolutionary with all the negative connotations that word can conjure: a zealot, cold, calculating, idealistic, paranoid, the prototype of the totalitarian bureaucrat capable of sending friends and colleagues to the guillotine for the ‘cause’. So I was curious as to what McPhee, a leading historian of the French Revolution, made of the man, and how he accounted for Robespierre’s condemnation to death of so many people.

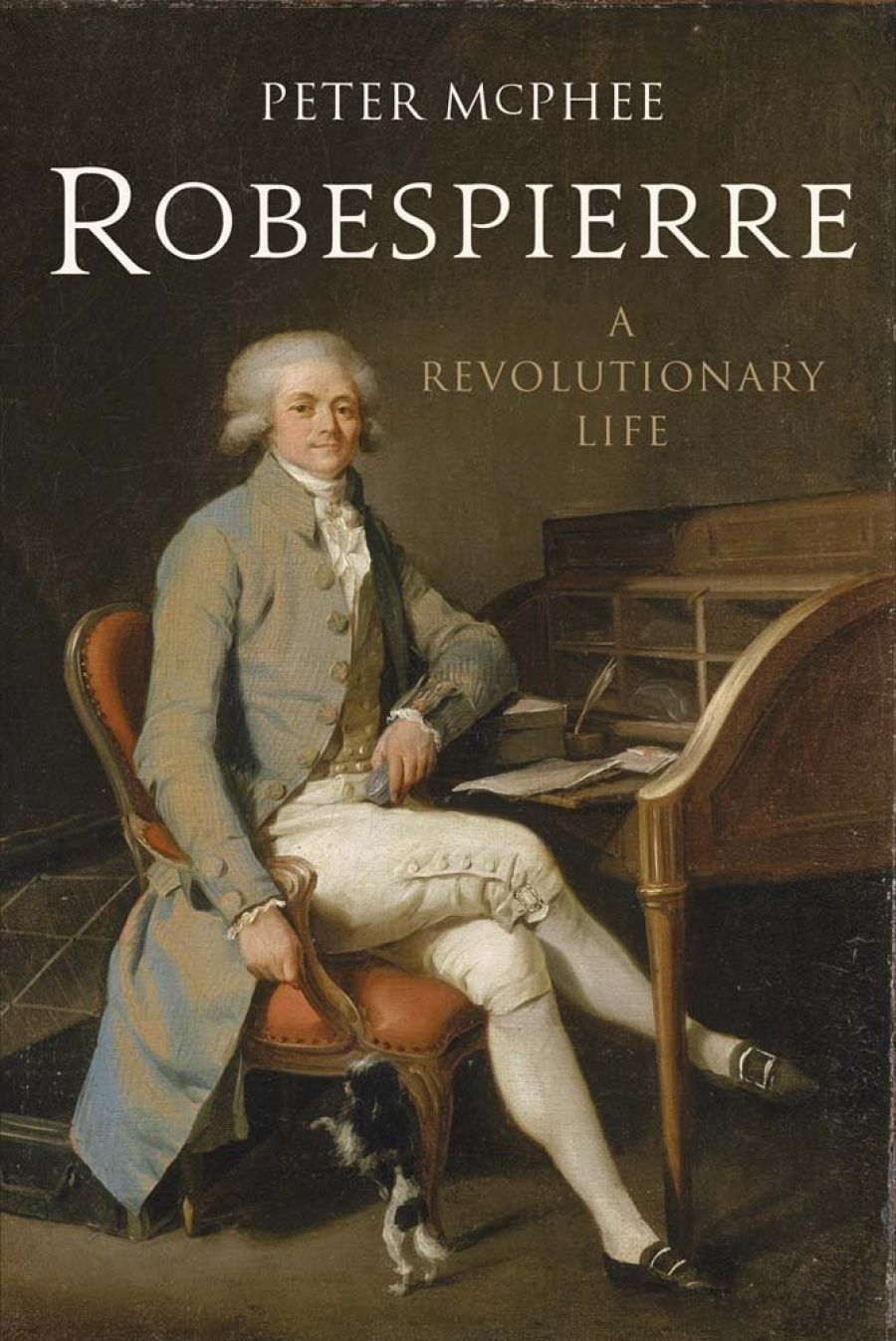

- Book 1 Title: Robespierre

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Revolutionary Life

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press (Inbooks), $49.95 hb, 333 pp

The reasons have to do with Robespierre’s own vision of a ‘virtuous’ society. That vision, argues McPhee, was linked to his childhood and youth. Conceived out of wedlock, Maximilien, one of four children, was six years of age when his mother died in childbirth. For reasons that are unknown, the father then abandoned the children to relatives, never to see them again. Rather than characterise this as one of the ‘traumas’ of Maximilien’s childhood – for which, admittedly, there is no evidence and a good deal of speculation – McPhee prefers to see in the extended family a group of ‘caring relatives’ who helped Maximilien cope with the loss of his parents. Possibly, but that version has been handed down to us by his sister, Charlotte, and was written many years after her brother’s death. There is no reason to doubt Charlotte’s word, but I wonder whether this was an early attempt at rehabilitation. From the start, McPhee displays a certain amount of empathy for his subject, but he also does what any good historian should: he questions what was previously taken for granted.

Like any biographical subject, Robespierre has to be understood as a child in a particular familial and social context. This McPhee does beautifully in the opening chapters. At the age of eleven, Robespierre was sent to Paris on a scholarship to Louis-le-Grand, one of the most prestigious colleges in the country. He was intelligent and incredibly hard-working. By the time he returned to Arras twelve years later to practise law, we are presented with a man whose character is virtually formed, a man who had developed a ‘will of iron’, who had a sense of duty, who believed that the poor deserved justice, who believed in democratic representation, and who learnt that ‘no authority was innocent’.

This is a man who had friends but who was close to no one (with the possible exception of Charlotte and his brother Augustin); who was talented and ambitious but appeared unassuming and humble; whose ideas were radical even for the day but who conformed utterly to ancien régime dress codes; who adopted the rhetoric of the Enlightenment but whose actions pointed to a certain callousness when others did not conform to his views; who thought he was doing the right thing but invariably alienated people of power and influence in the process. Robespierre was the type of character that would always polarise people, inspiring affection and even idolisation in some, hatred and indignation in others. The polarisation of attitudes towards Robespierre, argues McPhee, ‘personified wider divisions over the Revolution’.

Yes, but only once Robespierre became a public character. Before he entered public life in 1789, when he was elected to represent the Third Estate in the Estates General, he had already alienated most of the influential men in his provincial town. That is, the character traits that polarised people were already there and would become more pronounced as the pressures of office became more demanding. At Versailles, Robespierre quickly became caught up, but was by no means a key figure, in the tumult that led to revolution. To understand his trajectory is to understand those upheavals and the rapid change in political figures that went with it. It is also to understand the reasons why the Revolution became so violent that within a few years mother democracy began to devour its own children. McPhee explains all this exceptionally well, especially when it comes to understanding the increasing paranoia that permeated the political discourse and that in part led to the Terror. An inability to cope with political opposition within its ranks, and what were seen to be military betrayals once the war with Europe began in 1793, led Robespierre (and others) to call for measures against internal enemies. At that point, Robespierre, who had once spoken out against the death penalty, now demanded it for any attempts against the ‘unity and indivisibility of the Republic’.

If Robespierre’s political and social environment are important in any explanation of his character, so too were the moral precepts with which he was inculcated, chief among them the notion of ‘virtue’. If I have understood McPhee correctly, Robespierre believed the common people to be the embodiment of virtue (a notion that is not fully explained), and that the revolutionary assemblies were faithful expressions of that will. So far, so good. But then, as the internal political and external military crisis worsened, anyone seen to act against the revolutionary assemblies was accused of being in league with the enemy, even if one dissented in the name of the people. The revolutionaries’ world, Robespierre’s world, was neatly divided into a Manichean creation of good and evil, patriots and traitors, revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries, vice and virtue. Within the space of about four years, the Revolution had become a struggle to the death. It led to some convoluted rationalisations, such as Robespierre’s defence of the massacres of September 1792, in which around twelve hundred people were killed in the space of five days, as the legitimate expression of the ‘general will’.

One is inclined to believe that Robespierre’s political ruthlessness was there from a very early age. In his inaugural speech at the Royal Academy in Arras in 1783 – six years before the Revolution, and ten before he would be in a position of power – Robespierre drew on the reflections of Montesquieu to assert that ‘[A citizen] must not spare even the most beloved guilty person when the welfare of the republic demands his punishment.’ No one could have imagined that a day would come when Robespierre could act on the idea, but act he did. In 1794 he sent his colleagues and friends Georges Danton and Camille Desmoulins to the guillotine, although admittedly not without some wringing of the hands and not without having protected them for some time before that. He did so, it would appear, not because it was politically expedient to do so, but because he believed it was the right thing to do.

We come back to one of the central questions of biography: in what ways does the individual as historical agent shape or merely mirror wider social and political movements? Well, both, of course, but sometimes one more than the other. McPhee poses two questions at the beginning of his book: ‘was Robespierre the first modern dictator, inhuman and fanatical’, or was he a ‘principled, self-abnegating visionary’; and was the Terror necessary to save the Revolution, or was it an unnecessary waste of life? By the end, we have a clear idea of the answer and where the author stands: McPhee’s Robespierre is a visionary who helped save the Revolution. The problem was, as McPhee points out, that Robespierre, paranoid, mentally and physically exhausted, unable to distinguish between dissent and treason, lost his political acumen and did not know when to put the brakes on the killing machine that was the Terror. He appeared before the Convention on 26 July 1794 after an absence of four weeks, only to give a rambling, incoherent speech whose crux was a thinly veiled threat at a number of deputies he accused of betraying the Revolution. It was almost as though he were courting martyrdom. The next day, he appeared again before the Convention, and in the tumult that followed ended up shouting, ‘I ask for death.’ Later that day, he and a number of his followers, including his brother, were arrested. The suburbs of Paris failed to rise up to protect him; most of their political leaders had been sent to the guillotine. On the way to the Place de la Révolution to be executed, the same people who had once lifted Robespierre on their shoulders now jeered and insulted him. McPhee’s biography is full of insight, and one comes away with a deeper understanding of the man and his motives, but I still find Robespierre a little too ‘virtuous’ for my liking.

Comments powered by CComment