- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Military History

- Custom Article Title: Robin Prior reviews 'Anzac’s Dirty Dozen'

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This book is the second in a series compiled by a group of Canberra academics on the distortions they perceive to surround the writing of military history in this country. Before the book itself is tackled, a word should be said about the titles they have chosen for their two volumes. The first (published in 2010) is called Zombie Myths of Australian Military History; this one is entitled Anzac’s Dirty Dozen: 12 Myths of Australian Military History. As happens to many a poor author, these hideously ugly titles may have been imposed on the book by the publisher. If not, they need serious help when they title future volumes.

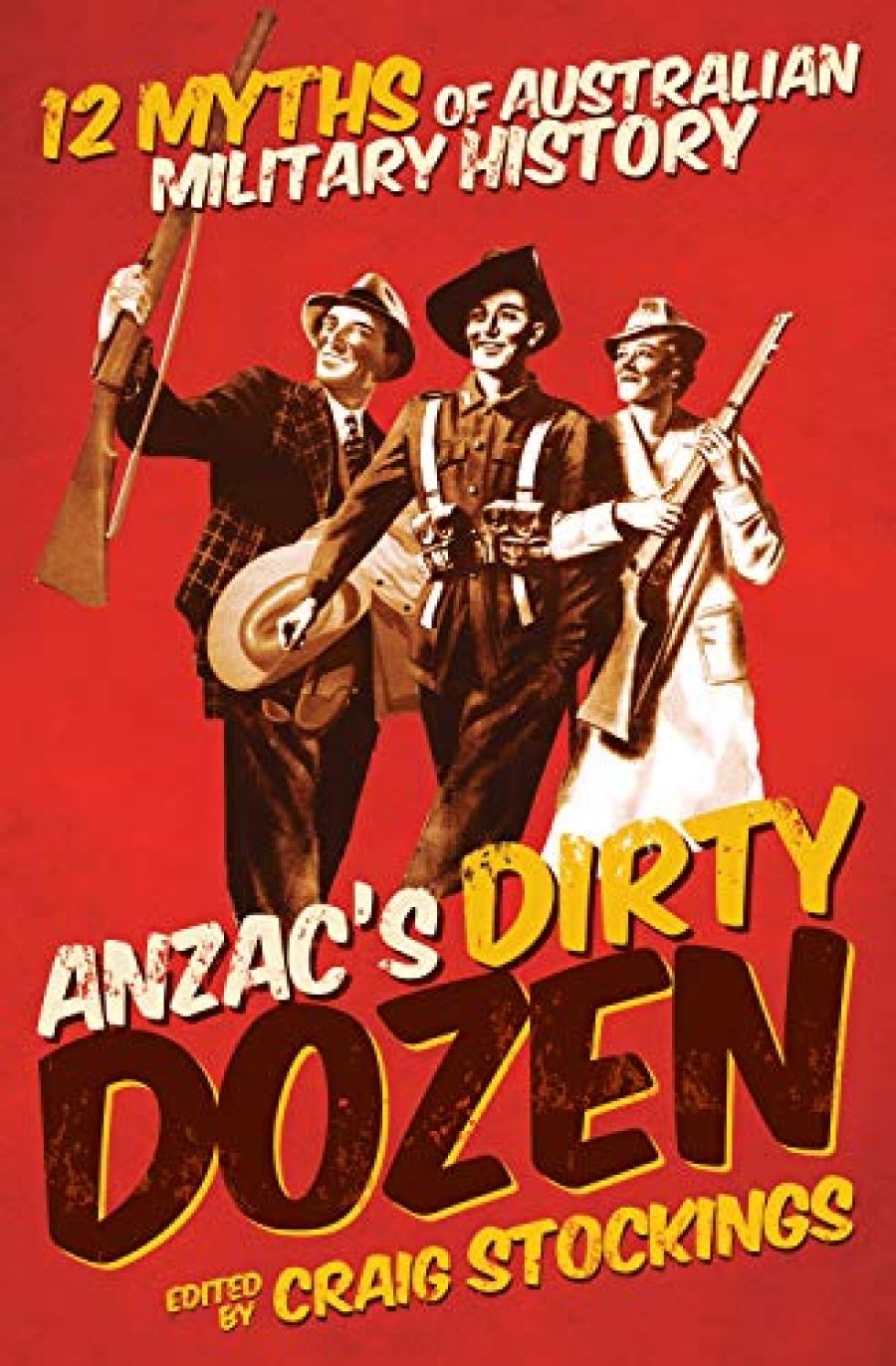

- Book 1 Title: Anzac’s Dirty Dozen: 12 Myths of Australian Military History

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth Publishing, $34.99 pb, 346 pp, 9781742232881

The second title, however, is more than just crude. It is inaccurate. This fact should have been noticed by one of the authors. Chris Clark’s chapter is called ‘What About New Zealand? The Problematic History of the Anzac Connection’. The main thrust of his argument is that Australia has appropriated those episodes in our military history where New Zealand has been involved and has elided the Kiwis. What this book does is to identify many myths where only Australians were involved and to write New Zealand in. By using ‘Anzac’ in the title the twelve myths examined become, by definition, New Zealand myths. Any reasonable Kiwi might object to this.

What of the other myths? There are some worthy essays here, but my feeling is that this team fired most of its effective broadsides in the first volume. There seems a diminution of importance in some of the myths discussed here, and in others the question of whether they are myths at all must be raised.

Let me take the chapter written by John Connor, ‘The “Superior” All-Volunteer AIF’. No one could quarrel with the judicious conclusions reached here. In the war of machines that was the Western Front, it made no difference whether a soldier was a volunteer or a conscript. The body of a volunteer could no more withstand machine-gun bullets or artillery shells than that of a conscript. The author is also entitled to point out that the First AIF was not the only volunteer force on the Western Front: the South African Brigade and the Newfoundland Regiment also fell into that category. But I wonder if the proposition is a myth at all. Those who trumpet Australian exceptionalism in the Great War do so mainly on the basis that we were Australians, not on the means by which we found ourselves in the army. Certainly, there is some pride in the fact that we fielded an all-volunteer force, but I know of few authors who have sought to rate armies on this basis. Who would, for example, denigrate the German army on the Western Front on the grounds that it consisted of conscripts? It is not that the author is unaware of this argument; it is just that it was dealt with in the Zombie volume.

Other chapters seem to deal with issues that are hardly mythic. Eleanor Hancock, in her well-written piece, argues that there is a myth surrounding Australian women in the world wars: that women managed to make an important contribution to the Australian war effort. She uses figures from the ‘paid workforce’ of Australian women to demonstrate how minor their efforts were compared to their sisters in Britain and Germany. But to personalise the issue – the first refuge of the reviewer – she traduces the efforts of the female members of my own family. My mother and grandmother both carried out war work – one for the Red Cross, the other on the farm. Neither was paid. My grandmother was ready to evacuate our store to the hills, where she would no doubt have taken part in Marrabel’s last stand. She would have fought them on the landing grounds and on the beaches had Marrabel possessed any. These women are representative of the vast number of women who worked unpaid on the family farm or in small business in Australia. These categories no doubt existed in Germany and Britain also, but not to the extent that they did here, due to the rural nature of our society. In any case, I am not aware that there is a vast mythology around this area of our history. I would be happy to be proved wrong.

It is good to see Michael McKinley’s splendid dissection of the US–Australia alliance, and it is good to know that there is still a place for Marxist analysis of Australian foreign policy. Marxist or not, there is much to agree with here, especially if the period from Vietnam to the present is the focus. It is difficult to see how our national interests have been served by involvement in every one of the Pacific conflicts during that time. But again, the question must be raised: where is the myth? Who exactly thinks that the alliance cures all evils? McKinley would answer that the alliance is accepted as a good thing, as an act of faith akin to being touched by medieval kings to cure scrofula. But does anyone think like that? Perhaps some in right-wing think tanks hold such views. But it seems to me that the Australian public takes a much more pragmatic approach to the United States: that it is generally useful to have a great and powerful friend, if only that friend would stop involving us in quagmires such as Vietnam, and if only our governments were more selective about when they should toe the US line. It is possible to disagree with the United States (Harold Wilson and Vietnam) and remain alliance partners. In short, I doubt whether the US alliance is seen as a cure-all. So, despite the cogency of the arguments set forth here, where is the myth?

The same can be said for other chapters. Peter Stanley insists that Australian history is greater than its military component. Who would disagree? Perhaps in their darkest moments Henry Reynolds and Marilyn Lake might lament the dominance of military topics in history publishing. But their own considerable output of books on non-military topics should give them heart.

Alistair Cooper insists that the navy has not had its due in our history. But, frankly, if all he can put forward is an obscure episode in the Korean War, perhaps he has answered his own question. There is little point in invoking John Reeve’s name in this context. Reeve deals in much larger themes than are put forward here.

There are other issues dealt with here that I consider non-myths. Whoever thought that Australians always play fair in war? Whoever thought that any country plays fair in war? There is not space to consider all the essays in this volume. All are worth reading – in particular Craig Stockings’s judicious conclusion. But the fact remains that it is time for this team to turn their attention elsewhere. There are just too many minor themes here. Zombie Myths was a book worth publishing. This volume is pushing the boundaries – it is a collection of myths too far.

Comments powered by CComment