- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Early in Charlotte Wood’s previous novel The Children (2007), one of Stephen Connolly’s sisters describes him as lost; she says he carries within him ‘a bedrock of resentment … never articulated and never resolved, but which has formed the foundation for his every conversation, every glance from his guarded eyes’. Readers may disagree with this harsh assessment as they read Wood’s new novel, Animal People, in which Stephen is the primary focus – this time more anxious than resentful. He is an inherently difficult character, but not a bad man. Wood unpacks him – sometimes ruthlessly – to reveal a person bewildered by the demands of all kinds of relationships.

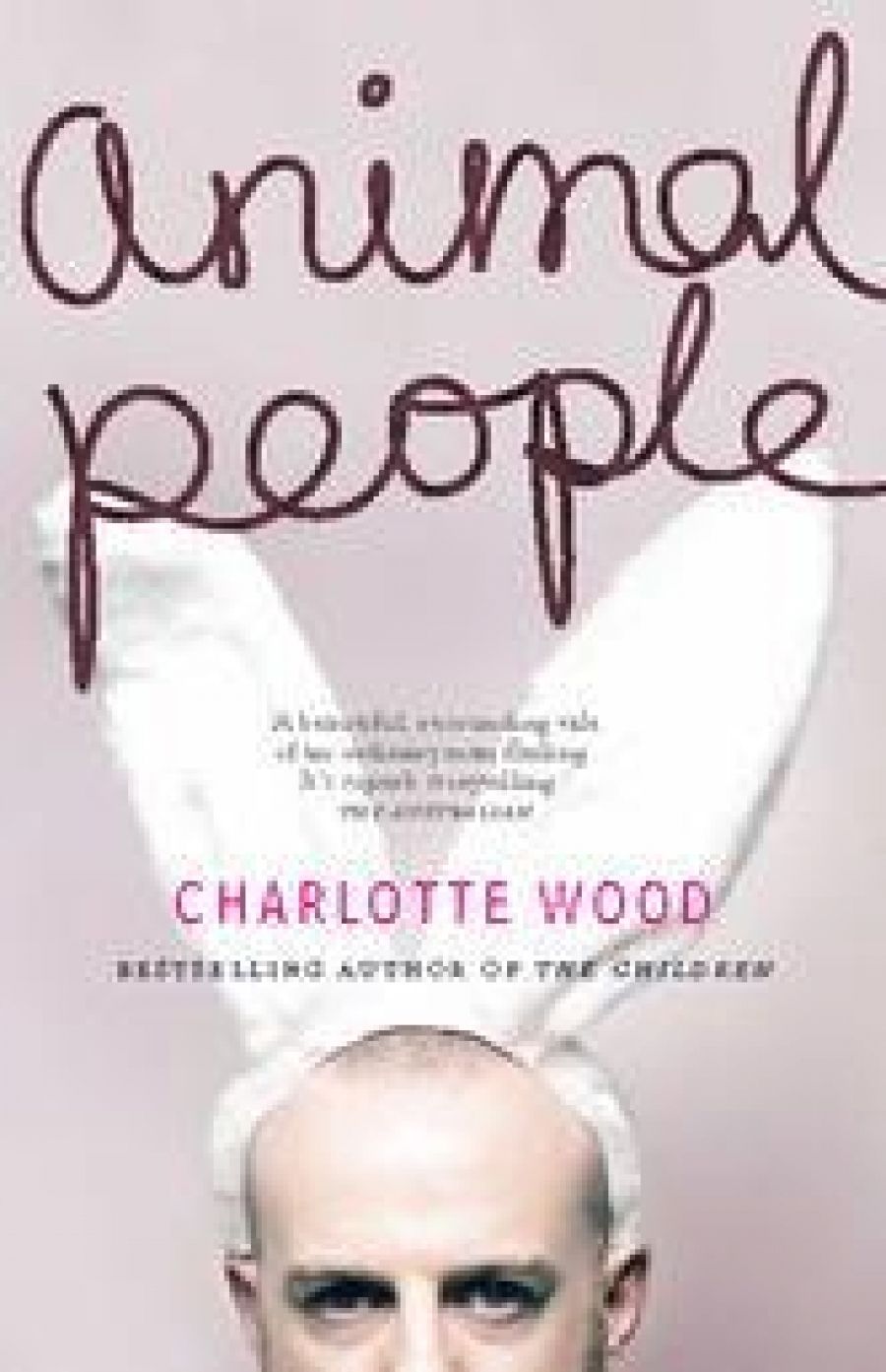

- Book 1 Title: Animal People

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 264 pp

Animal People spans a single hot and uncomfortable day. The events from morning until evening challenge Stephen and become increasingly surreal, from the thud of a body landing on his car, to encounters with neighbours, workmates and casual acquaintances, and, finally, a child’s birthday party viewed through the prism of exhaustion and anxiety.

The novel opens in Stephen’s apartment. Naked, he begins his day. As he sorts through his mail, the world begins to encroach. Reading a flyer about a lost ferret, Stephen recalls with revulsion the animal itself. He has seen the ferret and its owner before, and remembers its ‘horribly elastic body’, clicking claws, and the noise it makes; a ‘strange, high stutter’. The morning progresses with guilty masturbation in the shower, and a phone call from his mother; he lurches from one minor discomfort to the next. Even before he leaves the house he is ‘already defeated by the day ahead’. By the time Stephen retrieves a running shoe from beneath his bed on page nineteen, the reader is snared.

The ‘animal people’ of the book’s title are those who love animals. They appear first in the flyer about the lost ferret and continue as a thread through the story, allegorically illustrating Stephen’s real problem, which is less about animals than it is about people. Stephen does not like animals – for one thing, he’s allergic to animal fur – but he works at the zoo. He does not understand how people could possibly love animals. He has trouble understanding human relationships. All around him, people connect with animals and one another; all Stephen wants is to be free, to ‘get his life back’.

We also come to understand that Stephen knows there is something wrong with his inability to connect. On the bus we are confronted by a smelly fellow traveller who, unsteady on his feet, chooses the single available seat, next to Stephen. The insane muttering that follows is a kind of torture that Stephen believes he richly deserves. Later, a turning point occurs in a small but closely observed moment, as a peanut is removed from a child’s ear. This scene is written by an author at the top of her game. Pace is something Wood does particularly well. She speeds up the action during moments of rising panic and confusion, then slows the narrative when there is something she particularly wants us to see.

Like Stephen’s family and colleagues, the reader is never quite sure of this man’s worth. He is funny, intelligent, endearingly modest, but also passive, confused, and inarticulate, hopeless at standing up for himself. Luckily for him, Wood’s tender handling of this day in his life makes us look beneath the surface of Stephen’s inability to cope. Slowly, he begins to understand what he really needs.

Wood is a consummate observer of the human condition. She distils the dynamics of families and the interactions of daily life, and writes about them with honesty and restraint. It would be a mistake to imagine that the suburban setting and the themes of relationship and disconnection result in a lack of muscle. She communicates the detail of Stephen Connolly’s internal life so clearly that his mistakes begin to resonate with the reader; Stephen’s sense of disconnection and anxiety may be extreme, but he does become a kind of everyman, or everyperson. You don’t have to be a man to empathise with Stephen Connolly. His core dilemmas are universal. Wood frames them in a character whom it would be easy to dismiss in the hands of a lesser writer.

One scene towards the end of the book lingers in the mind. Stephen’s girlfriend, Fiona, experiences an almost physical shock in response to a revelation that she hadn’t anticipated, though the reader has known since early in the novel. Wood’s mastery of her craft is never clearer than here. We don’t want Stephen to mess this up, if only for the sake of the people who love him. But we know he will.

Aside from the pleasure of the narrative, the gatefold binding and Mrs Eaves typeface add an extra dimension to this paperback edition. As eBooks become more popular, it is encouraging to see a publisher paying attention to details that enhance the sensory experience for those readers who still enjoy a physical book.

Comments powered by CComment