- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is easy, too easy, to feel familiar with Clint Eastwood. However fully we realise that he is just another actor playing a role, part of us wants to believe that he speaks to colleagues in terse catchphrases and squints at friends and family with profound contempt. Almost invariably, his tough-guy image sets the terms for assessments of his work as a director – whether he’s seen as the Last Classicist or merely as a hardened old pro who gets the job done. To be sure, in conversation with journalists Eastwood has often been willing to play up to his laconic reputation. My favourite example came when he was asked how he approached the adaptation of The Bridges of Madison County: ‘I took all the drivel out.’

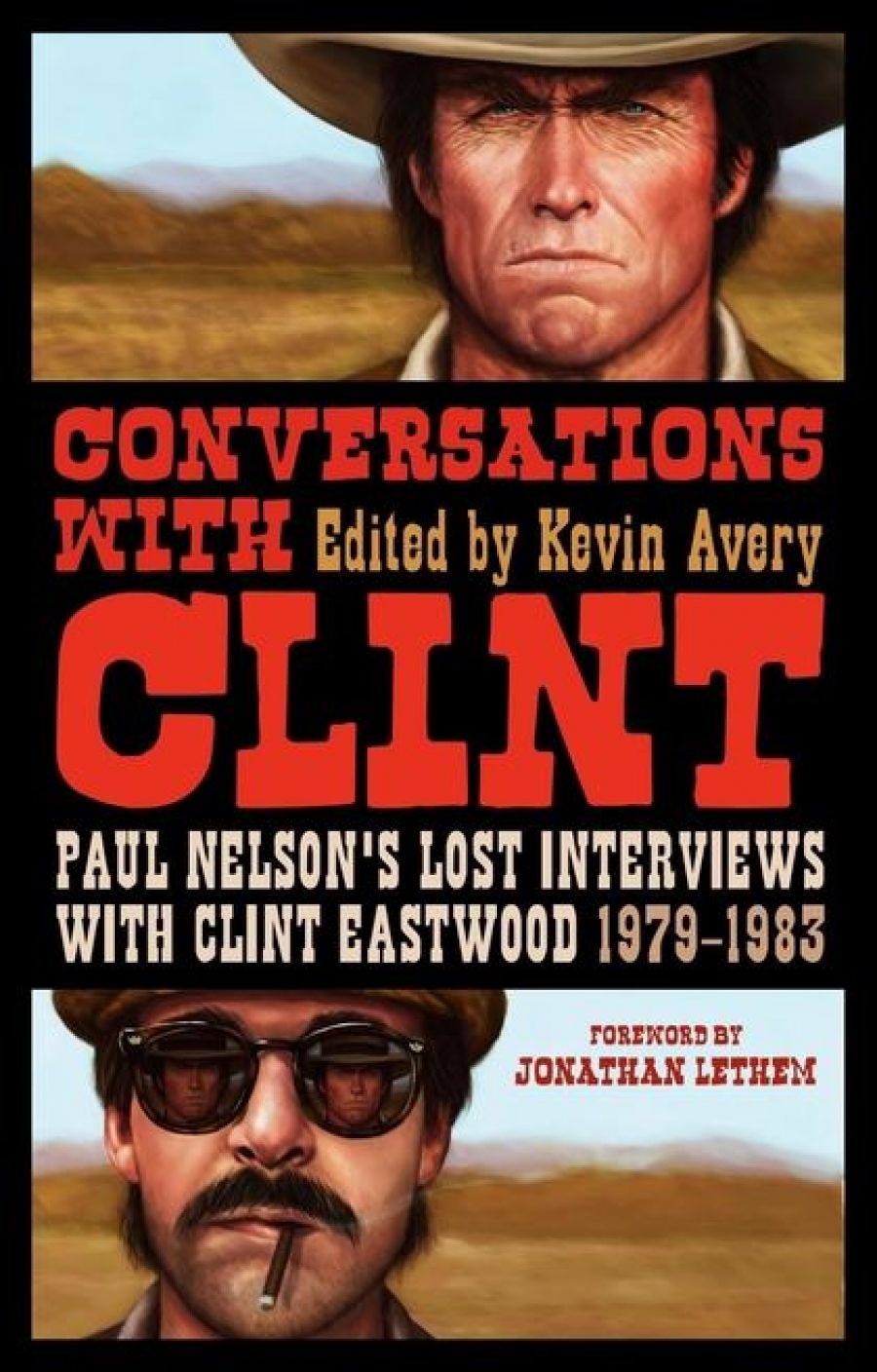

- Book 1 Title: Conversations with Clint

- Book 1 Subtitle: Paul Nelson’s Lost Interviews with Clint Eastwood 1979–1983

- Book 1 Biblio: Continuum Books (Palgrave Macmillan), $29.95 pb, 256 pp

In reality, if Eastwood resembles any of his screen characters, it is probably the disc jockey from Play Misty for Me (1971): the artist as a smooth transmitter of other people’s material, who understands how to sustain a mood till it turns into something ‘real nice’. So many of his gifts relate to intangibilities of tone and rhythm: an ability to extract the most from a bit player or a location, a readiness to indulge digressions without breaking the narrative flow.

Eastwood has confessed that in everyday life he tends to be reserved, even shy. It may say something about his wariness of fame that Misty, his first film as director, centred on a celebrity pursued by a crazed admirer (Jessica Walter). Decades later, his masterpiece, Unforgiven (1993), portrayed a different but just as off-putting kind of fan, a hack Western author (Saul Rubinek) who literally wets his pants when he gets near an actual gunfight.

Happily, nothing like either scenario occurs in Conversations with Clint, assembled from transcripts of interviews conducted some thirty years ago by the rock critic Paul Nelson for a Rolling Stone article that never made it to print. Nelson was not only a fan but also what we would now call a ‘fanboy’ – to the point of purchasing his own .44 Magnum after watching Dirty Harry (1971). As the transcripts show, he and Eastwood soon found a genuine personal connection; still, the relationship betweencritic and artist is necessarily a complex one, especially when the critic is prone to hero worship and the artist has been charting macho power struggles for most of his career.

The Nelson of this book is not above flattery (‘Boy, if it were possible to make a good Gatsby, you would be perfect’) while still insisting on his status as Eastwood’s intellectual and creative equal. For his part, Eastwood relishes the chance to sound off on a wide range of subjects, from shyster lawyers to Muhammed Ali’s comeback to the state of the American economy; on the whole, he registers as more of a consensus-builder than a maverick, despite his justifiable pride in having arrived at his opinions by his own road.

Inevitably, there are glimmers of tension, notably when the instinctively conservative Nelson denounces some trendy phenomenon – such as MTV or Woody Allen – and Eastwood, at once more cautious and more open-minded, declines to follow suit. Conversely, the pair seem to enjoy each other’s company most when they happen upon a mutual object of loathing, as in the hilarious pages spent trashing Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980). (Nelson: ‘This man does not seem to be living in the real world any more.’ Eastwood: ‘It’s dead as a dick.’)

As an exploration of Eastwood’s output in his first dozen years as a film director, Conversations with Clint is more suggestive than definitive; in line with its subject’s famous love of jazz, these dialogues could be compared to jam sessions, particularly when the musician Warren Zevon stops by to offer his own stoned-sounding reflections (‘Anything that passes as art/entertainment should stand up to the analogy of being a joke’). Among other things, the book confirms how seriously yet playfully Eastwood has always approached his craft as an actor, as suggested by his fond memories of drama classes from his youth, ‘playing chairs and tables and banging your head on the floor and doing crazy improvisation’.

Judging by the samples available online, Nelson’s journalism has not aged well; but the same could be said of many scenes in Eastwood’s early films, from the ‘frolicking lovers’ montage in Misty to the rape in High Plains Drifter (1972). As arranged and annotated by Kevin Avery, the transcripts convey a story which neither man planned to tell at the time – the story of an encounter between two very private, oddly delicate sensibilities that could only have occurred at one specific moment. Nelson ended his days as a video store clerk, socially isolated and plagued by short-term memory loss; Eastwood, now in his eighties, still ranks as one of Hollywood’s most prolific and successful directors, as well as a universally recognisable star.

Increasingly blocked as a writer, Nelson seems to have fallen victim to his own impossibly high standards – something that always separated him from his hero, who was and remains supremely pragmatic. Perhaps we are meant to deduce a moral here? I can only think of Eastwood’s great line as he looms over Gene Hackman at the end of Unforgiven, a second before he pulls the trigger: ‘Deserve has got nothing to do with it.’

Comments powered by CComment