- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

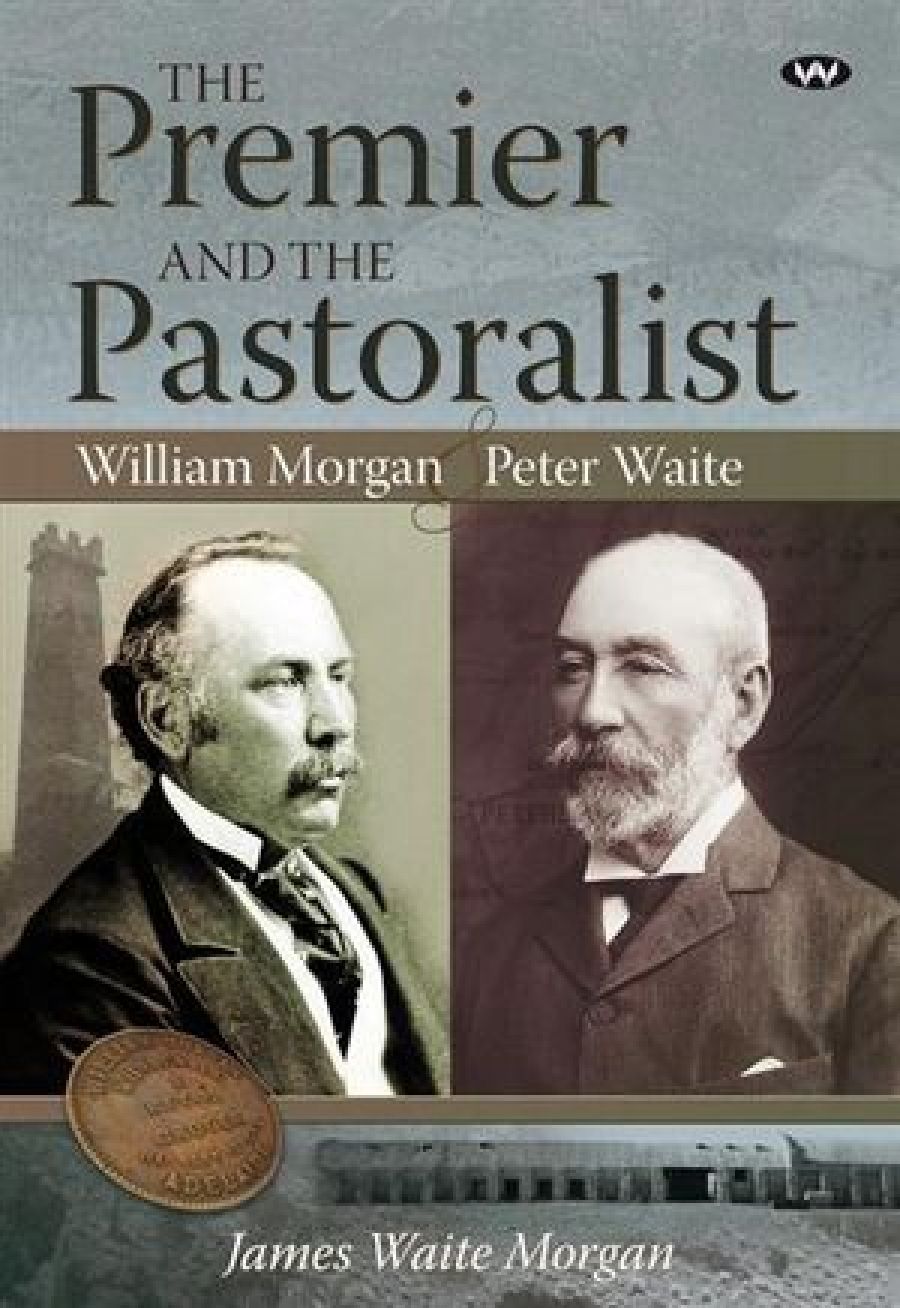

Family histories have their limitations. One compensation is to discover famous or infamous ancestors. In most Australian states, disinterring a convict becomes a badge of honour. In South Australia, having a nineteenth-century premier and a noted pastoralist in one’s lineage advances a claim to fame ...

In a slim volume, it is not until page 115 that the protagonists are described as ‘friends’. On the following page one learns that ‘William Morgan, popular man-about-town, had promoted the entry of Peter Waite, the dour pastoralist, to the Adelaide Club’, but that is the only direct link. This is most peculiar: Morgan and Waite were near neighbours in their mansions, Urrbrae and Netherby, respectively, and their sons were friends. The year is 1878. Morgan, aged forty-nine, has just five years of his life to run; the forty-four-year-old Waite will live until 1922. Essentially, then, the book is not about a relationship but rather the biographies of two men, and it is the pastoralist who receives the better treatment.

What do we learn about Morgan? After arriving in Adelaide in 1849, he has some success on the Ballarat goldfields in 1851. He then returns to South Australia where he builds a successful grocery business, marries Harriet Matthews, begins producing a family of nine children, is a founder of the Bank of Adelaide, enters the Legislative Council despite making an appalling speech devoid of policy, dabbles in mysterious mining ventures in New Caledonia, holds no ministerial office for eight years, and then becomes chief secretary in the third and fourth ministries of James Boucaut. Finally, he serves as premier for two years and nine months, from September 1878 to June 1881, a record at that time.

Plainly, Morgan is a significant mover and shaker in a boom period. However, apart from a brief relay of his achievements in establishing free and secular education, and providing significant public works, it is difficult to determine how he made his rise to power, who supported and sustained him.

Eighteen sixty-seven was a threshold year. Not only did Morgan enter the Council, but he was proposed for membership of the Adelaide Club by Richard Hanson and John Hart (two former premiers), and also acquired Hart’s former home, Netherby. More ought to be made of such connections, especially that with Boucaut, a dynamic politician who was premier four times before retiring at the age of forty-six to become a judge of the Supreme Court.

Morgan’s end comes swiftly. His ‘genius for business’ is limited to his Currie Street grocery, and increasing money pressures bring his resignation in March 1876 as chief secretary and as premier in 1881. He refuses a baronetcy, accepts a knighthood, travels to London to meet bankers, catches a cold, and dies of pernicious anaemia. It is a life that doesn’t add up.

It is easier to note the progress of Peter Waite, who arrived in Adelaide in 1859 and quickly fell under the influence of pastoral pioneer Thomas Elder, whose family he had known in Scotland. Waite immediately began working as a jackaroo; three years later, Elder helped him to purchase the Paratoo lease. After taking over the Pandappa lease, he imported Scotswoman Matilda Methuen to be his wife in 1864, started a family of eight children, and added the Mutooroo lease in 1873.

These leases ran north-east from Burra to the New South Wales border. One of the most interesting sections of the book describes fencing 1000 square miles of open country into 100 paddocks and supplying water through the construction of tanks and dams. In the 1870s, Waite became Elder’s right-hand man as he extended his management over the Beltana, Murnpeowie, and Cordillo Downs stations, the latter on the edge of gibber plains near the Queensland border.

From 1883 until his death, Waite served as chairman of Elder Smith & Co.; the company floundered at various times. In the new century, Waite had no family member to carry on his work, so his main legacy to South Australia was his gift to the government of the Urrbrae estate, which became the Waite Agricultural Research Institute (now Waite Campus of the University of Adelaide) and the Urrbrae Agricultural High School. Morgan’s legacy is less certain: development of state education, the railways, and playing a part in building the major cultural institutions of Adelaide.

James Waite Morgan, who spent many years operating major properties, is at his best writing the early chapters on Waite. He knows the country and what was required in an earlier age to make it useful for grazing sheep.

Unfortunately, the book lacks a coherent narrative and is often larded with contradictions and speculation that rely on family lore, hearsay, and tittle-tattle rather than on reliable evidence. Perhaps the worst contradiction appears on page seventy-one when Boucaut and Morgan are said to have provided South Australia with ‘unprecedented continuity of office’. Six ministries in six years is a rapid turnover.

Like all of Wakefield Press’s books, The Premier and the Pastoralist is elegantly produced and contains superb illustrative material, particularly the maps of the pastoral leases. However, as a work of history which might have merited wider readership, it represents a missed opportunity.

Comments powered by CComment